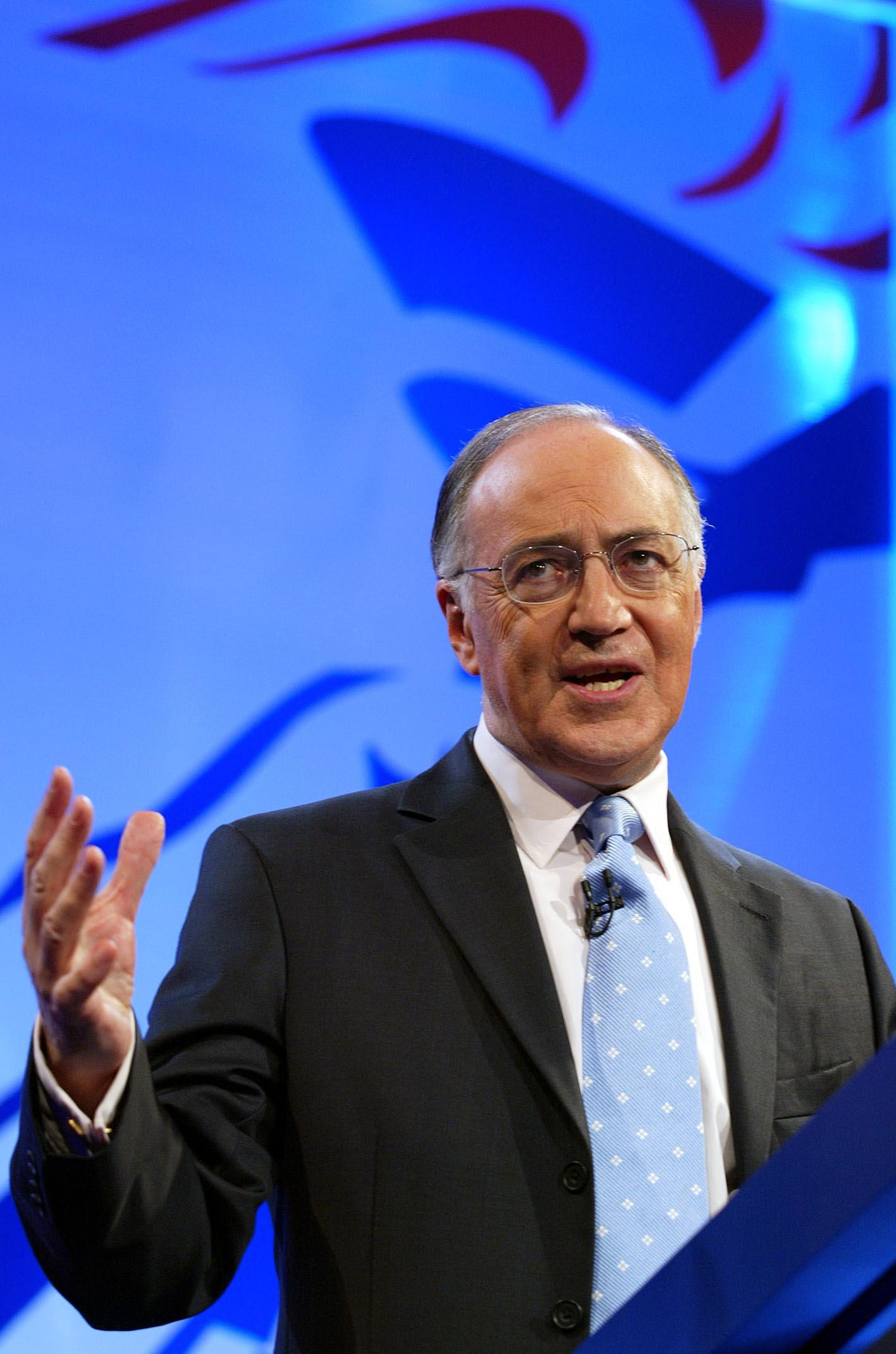

Michael Howard – 2003 Speech on the Responsible Society and the Voluntary Sector

The speech made by Michael Howard, the Leader of the Opposition, at the Charities Aid Foundation annual conference on 13 November 2003.

First, may I thank you for inviting me to speak at your Conference today. You invited me to address you as Shadow Chancellor. But I am delighted to do so in my new role as Leader of the Opposition. It is, in fact, the first major speech I have delivered since my acceptance speech. That I should do so at a Conference with the theme `Mission Tough, but not Impossible’ seems to me to be rather apt.

Indeed, the qualities which your Conference publicity says are required for getting your job done – namely ingenuity, creativity and resourcefulness – are qualities which any Opposition requires too.

We have much to learn from you. Ingenuity, creativity and resourcefulness have characterised the work of the Charities Aid Foundation throughout its entire history – and, indeed, have characterised the charitable sector as a whole. And the discussions you are having over the course of this Conference, together with the exhibition and Cyber Café, demonstrate these qualities in abundance.

Responsibility

At the heart of what I have to say lies the concept of responsibility: the responsibility that people have towards their neighbours; and the role of government in facilitating and fostering that sense of responsibility.

It is important for politicians to keep sight of both these aspects of responsibility. Government can never supplant the responsibility that people themselves have for each other – as families, as local communities, as a society, and as fellow human beings. I do not accept that personal responsibility can somehow be `nationalised’ or handed over wholesale to the State. But I also do of course accept that there is a proper role for government.

The Conservative Approach

My party has a long and proud record. Social housing provides a good example. Disraeli’s path-breaking legislation in the 1870’s was the start. In the 1920’s and 1930’s Conservative ministers laid the foundations for what later became modern council housing and in the 1960’s it was Keith Joseph as Housing Minister who recognised the potential of housing associations.

Modern social services departments are largely the product of Conservative legislation. The landmark event was the decision by Keith Joseph and Ted Heath to go ahead with Lord Seebohm’s recommendation to set up local authority social services departments. And most of the important legislation that underpins the work of a modern social services department was passed by recent Conservative governments. As a result of the 1989 Children’s Act, we have one of the most coherent and sophisticated legislative frameworks setting out the principles for children’s policy in the world.

The 1990 National Health Service and Community Care Act was an important step in making care in the community a practical reality for people who wanted to choose it and it ended the perverse set of incentives that sometimes obliged people to accept care in circumstances where they had no real choice.

The 1990 Community Care Act directly led to the position where we now have a genuine mixed economy in the provision of social care. The public sector, through local authorities, still directly provides and organises social services itself, but local authority social services departments also fund other organisations like voluntary organisations and charities which directly provide care.

Today many social services departments spend over 50 per cent of their budgets in the independent and voluntary sectors.

There are many occasions where the voluntary sector can provide services in a new and imaginative way or in a way that is more flexible and provides the users of the service with greater choice. These developments in social services illustrate that there will often be occasions when the state should step aside from directly providing the service itself and fund other people like voluntary organisations to do so instead.

Getting the Economy Right

That role of government is many-faceted.

Too often politicians compartmentalise their policies. Much of what I have to say will, indeed, relate specifically to charities and how government can help them – or, at the very least, not set obstacles in their path.

But there are wider responsibilities too. Governments must help to create the economic climate in which people are encouraged to show responsibility for others. That means a climate in which taxes are kept low and enterprise is encouraged.

The promotional literature for this Conference notes right at the start that high consumer debt and economic uncertainty have hit those in the charitable sector, `dependent as they are’, it says `on the surplus cash of their supporters’. It is true that when real net disposable earnings are falling, as they have been doing as a result of the tax rises which came in last April, people will be less able to donate money to the voluntary sector. And people will feel similarly constrained if they are concerned about their future financial security, as a result of the record combined levels of consumer and government debt which now exist.

There are some ironies here. Governments which seek to create an enterprise climate, to keep taxes down, to limit the role of the state, are sometimes accused of fostering selfishness. You will not be surprised to hear that I do not accept that. It is no coincidence that charitable giving is often highest in countries – such as the United States – which have adopted the free enterprise model.

But, while an enterprise economy may assist in the fostering of a responsible society, this is by no means the limit of the government’s role.

Other Government Responsibilities

Governments themselves have direct responsibility for the alleviation of need and for the funding, and in some cases provision, of important services. Of course the last six and a half years have shown that merely levying ever higher taxes is rarely if ever the best way to fulfil that responsibility. While taxes have risen, expectations have been disappointed. We believe that reform is required – of public services and of welfare.

These government responsibilities will not always involve the not-for-profit sector. But sometimes they will. And this brings me to the government responsibility I want to focus on today: the responsibility to protect and promote a vibrant voluntary sector.

The Importance of the Voluntary Sector

Why is this important?

One reason is a practical one. Quite simply, there are some things that charities can do better. They are often more responsive, more flexible, and more innovative than the state sector, as a result of being less rigid and less bureaucratic.

There are also philosophical reasons. Voluntary activity is a vital channel through which people can show responsibility for others in society – whether those next door or those at the other side of the world. That is a healthy thing in itself. A thriving voluntary sector, by virtue of the very fact that it is voluntary, is a sign of society in which people are willing to show that responsibility.

60 Million Citizens

I believe Government can encourage the voluntary sector in two principal ways.

First, it can encourage people to be responsible for others through voluntary activity, by donating their time or their energy or their money to voluntary organisations.

Second, it can give voluntary organisations themselves more freedom, and more opportunity, to serve the communities they were established to serve.

Some policies to back these principles up are set out in our Green Paper, Sixty Million Citizens, which was published earlier this year.

The central idea behind the paper is the need to ‘unlock Britain’s social capital’. That is not referring to the state or to the apparatus of government, but to people giving of their own time, energy, money – and allowing them more say over the resources they already provide.

Here I want to pay a tribute to the work of Iain Duncan Smith. He recognised the importance of the voluntary sector in Britain, and of policies to promote the voluntary sector to the Conservative Party. It is my intention that such policies will become a core component of our programme for government.

The Green Paper sets out a range of proposals. These do not yet represent official Party policy. We have been consulting on them and considering the best ways to take them forward. This work will continue.

Today I want to outline some of these proposals.

They include the establishment of a new Office of Civil Society, championed by a Cabinet minister. We want to ensure that the voluntary sector is no longer under-represented and overlooked when important policy initiatives are being developed.

And they include specific suggestions under the two broad themes I have set out: encouraging people to be more responsible through voluntary activity; and freeing voluntary organisations themselves to get on with the work they were established to do.

Encouraging Individual Responsibility

The work of the Charities Aid Foundation in showing people and business how they can give tax-effectively is invaluable. You have pioneered ideas such as the Charity Account. But the fact that only about one third of individual giving is tax efficient is a sign that there may be room for government action too.

First we have been looking at the costs and mechanics of tax relief on spontaneous giving, in recognition of the generous work of those who collect money through, for example, collection boxes.

The Green Paper also proposes that people in receipt of universal benefits – such as the state pension or child benefit – should be given the option of donating these benefits to charity.

The idea of government-matched funding, focused on endowments for poorer areas, would also encourage other charitable or private forms of giving.

But people don’t just donate money. We want to support those who donate their time to voluntary causes too. As in the case of voluntary activity as a whole, volunteering should be encouraged both for its practical usefulness and for its inherent value as a core component of a responsible society.

So the Green Paper proposes the creation of a volunteer bounty for every volunteer or mentor signed up to tackle certain social challenges and who becomes part of an accredited training programme.

The Voluntary Sector

Those are some of the ways in which a Conservative Government would encourage people to be more responsible for others. But that is not all we need to do. Voluntary organisations themselves need to be given greater opportunity to serve the communities they want to serve.

That means a better legal structure. We have pressed the Government to make room for a Charity Law Bill in its legislative timetable.

Sometimes what is required is just for government to get out of the way – or, at least, to make the bureaucracy of government as straightforward as possible.

We want to see less red tape in the grant-making process, and have suggested a single application form across government departments and less bureaucracy for those organisations which belong to approved voluntary sector umbrella groups. And more fundamentally there is room for a greater emphasis on the results which organisations achieve rather than the precise means by which they do so.

Of course where public funds are involved there are bound to be conditions attached. That is perfectly legitimate – and proper. But we do not want to see an over-zealous interpretation of those rules. Because risk aversion comes with no cost to the officials involved, there is an inbuilt tendency in Whitehall to implement legislation more rigidly than the legislators intended.

Voluntary organisations need someone there to put the other case. Our suggestion of “Bureaucracy Busters” has this in mind. They would have the authority to curb over-zealous application and interpretation of regulations, and the powers to require fast communication and decision-making across government departments. They would also report back on those regulations which could be eliminated.

After all, too much red tape from the centre risks negating some of the very attributes which make the voluntary sector so valuable in the first place. We have seen how the Government’s rigid and centralised target culture is suffocating innovation and local discretion in the public services. The last thing we want is to see it suffocate these values in the voluntary sector too.

There are of course plenty of other ways in which voluntary sector organisations can be encouraged by government.

For example an unfair competition test would protect not-for-profit organisations from being usurped by handsomely-funded government initiatives.

We want fairer treatment for faith-based organisations.

And, more radically, we have suggested a right for community organisations or entrepreneurs first to manage and then to assume ownership of under-used public sector assets such as community halls, parks or vacant land, subject to necessary safeguards. Such Community Asset Trusts could then apply to manage and deliver other local public services.

Indeed, our wider reforms to the public sector, in which more funding will follow the users of the service rather than the providers, will also open new opportunities for the voluntary sector. If voluntary organisations are able to provide services which people prefer to those provided under existing structures, then increasingly they will be able to do so.

Protecting Charities from Government

So these are all ways in which we see government helping the voluntary sector.

But I know that a note of caution is needed. I have already alluded to the fact that too much attention from government can put at risk the very qualities which make the voluntary sector unique – diversity, innovation, flexibility.

Such attention may well be well-meant. But being smothered by an elephant is no less painful if there is no deliberate malice involved.

We must seek to ensure that such smothering does not occur.

In some cases, where government has a specific end in mind, it may well be that voluntary organisations will adapt to meet that end, if given the chance, more effectively than statutory organisations would do so. But we do not want to see an unintended diversion of activity away from those areas where the voluntary sector itself has identified need. We want to encourage – not discourage – social entrepreneurs to find new ways to meet those needs.

Our Green Paper proposes mechanisms to avoid, for example, the problem of `mission creep’ – the diversion of promising community enterprises from their start-up goals and activities. This is made worse by the government’s habit of changing its own mission priorities. Instead, a new system of ‘Mission Reward’ would reverse this ‘mission creep’ and direct the flow of public money and assets to social enterprises that are successfully delivering sustainable community renewal.

Under our proposals, proven successes would win an escalating series of presumptive rights to public funding, control of public assets, and the opportunity to improve delivery of publicly-funding local services.

Conclusion

These are all fresh and innovative ideas which I hope you will find appealing.

But I appreciate that some voluntary organisations will find some of the ideas more appealing than others. All, I imagine, will be keen to embrace our offer of less red tape and less interference. But some, precisely because you value your independence from government, will be less keen to enter into new partnerships for the delivery of services.

And my message is this: our invitation will be just that – an invitation. We will not feel offended if some turn it down! Many in the not-for-profit sector will feel their priorities and ethos would inevitably be compromised in any such partnership with government. And they will continue to fulfil a role which is just as valuable. A thriving voluntary sector, in all its diversity, is an end in itself. It is the very embodiment of the responsible society which Conservatives wish to see.

So I hope that what I have outlined today is a distinctly Conservative agenda. I believe it goes with the flow of the sector in which you work.

It is an agenda based on the concepts of freedom and opportunity. These are often challenging concepts. But they are essential if we are truly to create a society in which people are able to be more responsible for each other. And at a time when people and voluntary organisations alike are looking for less of a stranglehold from the state, they are concepts whose time has come.