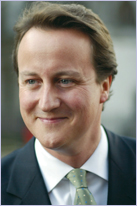

The speech made by David Willetts, the then Shadow Secretary of State for Innovation, Universities and Skills, on 31 October 2007.

The decision to go to university is one of the most important that a young – or older – person will make in their lives. Having a degree means considerably enhanced earning power. But it also means much more. A university education should be an intellectual, cultural and social experience. It is about learning to question and to think independently. It is about meeting people from all over the world, and from different cultural and social backgrounds. Increasingly it is also about learning to juggle the conflicting demands of study, a part-time job, and a personal life.

In recent decades the higher education system has seen rapid expansion and great change. This has been a good thing. More young people have enjoyed the benefits of higher education. And despite the large increase in the number of people studying at UK universities, the OECD revealed last month that the graduate premium has not declined. A degree is worth as much today as it was ten years ago.

Yet we need to be clear about the direction in which we are heading, and about the impact of this rapid change upon students and upon institutions. It is not enough to simply propel more and more students into universities, with little regard for the experience they have, or for whether they complete the course. Today’s students are savvy consumers, and we need to make sure that we are giving them the quality of experience that they expect and deserve.

Frequently British universities are talked about in terms of their research, or their value to business and to the economy. These missions are clearly vital. But somewhere along the way we seem to have lost sight of one of the most important functions of a university. Gordon Brown can only see universities as factories, churning out research papers and the practical skills that will aid economic growth. That is indeed very important, but it does not fully capture the real value of education. It is almost as if people are afraid of just saying education is a good thing in itself. That comes from a loss of confidence in the fundamental importance of transmitting a body of knowledge, a culture, and ways of thinking from one generation to the next. It is one of the most important obligations we have to the next generation and we are failing to discharge it.

Not only is that utilitarian view of higher education a bleak one, it is also counter-productive. People do not become lecturers or teachers because they want to help maintain the national stock of human capital; they wish to pass on a love of their subjects. Equally, students will not engage with subjects out of a desire to improve the trend rate of growth. It is only by making sure that tutors are allowed to teach their subjects and students are allowed to be inspired that we can achieve these goals. The route to creating a well-educated workforce is a good student experience.

Crucial to this debate, of course, is the issue of how we fund our universities.

Tuition Fees

We support the idea that those who benefit from higher education should meet some of the cost of their degree. This is achieved through the introduction of a variable fee of up to a maximum of £3,000. There have been serious teething problems with top-up fees. There is a general air of mystery and confusion surrounding bursaries. Lots of people do not understand that the fees do not need to be paid up-front.

This system of fees, loans and top-up fees has been fixed until 2010, but it may well continue afterwards. What happens afterwards will be dependent upon the result of a major review into the success of the current regime which will examine the results of the first three years of variable fees. This Government review will examine the impact of the arrangements on higher education institutions; the impact on students and prospective students; and will make recommendations on the future direction of the policy.

We are not calling for the cap to be lifted and we are not calling for it to be lowered. Nobody knows enough about tuition fees and their impact to make any decisions at all on this issue. Especially not the Government. Rather than waiting until 2009 to call this review, why does the Government not start now? A proper review takes time. We do not need to make a decision any sooner than the Government suggests, but why waste this two years which could be spent collecting data, talking to people or analyzing what is happening?

We would urge the government to set up the independent review group to look at the situation now.

There is enough data on admissions and drop-out rates which they can start working on as it is.

And if the review is to be successful, they will need to talk to students. They need to look at the financial support mechanisms that are in place. Why isn’t the bursary system that was set up to help those most in need working? Where has the money from fees gone and how much of a difference has it made to the quality of teaching? Steadily increasing application figures suggest that contrary to many fears, the £3,000 fees have not deterred students from applying to university. The latest figures released by UCAS this month show that record numbers of students applied to UK universities this year. The total number of people applying for full-time undergraduate courses at universities and colleges in 2007 was 532,000 – a rise of 5.4% on 2006. Moreover, the number of students from England accepted into the system this year has risen by more than the average – up 6.4 per cent on last year, compared with an increase of just 0.5 per cent in Scotland where fees have not been introduced.

They will need to look at whether the prospect of increased debt is putting poorer people off the idea of a university education, and whether this can be overcome. Despite constant talk of widening access to universities, the Government has failed in its mission to encourage more young people from disadvantaged backgrounds to go to university. The proportions of students from different social groups remain depressingly static. In 1990 77 per cent of children from socio-economic group A made it to tertiary education, and 14 per cent from socio-economic group D.

If the review is to be successful, they will need to talk to Vice-Chancellors. Where will UK institutions be financially by 2010 and how will this compare with universities in the US, Europe or Asia?

Leitch was absolutely right when he highlighted the need to “embed a culture of learning” into our society and our workforce. Yet how can we foster a system of lifelong education if we are not thinking hard about creating the right experience for part-time and mature students?

If we are going to understand fully what is happening in higher education, we also need to wake up to the fact that the university environment is changing. Brideshead won’t be revisited. One in five students live at home while studying. One third of students now juggle a part-time job alongside their studies during term-time. Over the past five years numbers of mature students have risen by 18%: in 2006, nearly 70,000 over-21s were accepted on to higher education courses. And the Higher Education Funding Council for England is keen to stress that with an ageing population, in the decade following 2010 institutions will be under serious pressure to recruit more mature students in order to fill their places and balance their books.

They will need to look into the arrangements for part-time and mature students. One of the best ways of widening access is not just to get people to take full-time courses at universities, but to encourage part-time learning. There are good reasons for people not to take three or four years out of their working lives. We should not dismiss them. Currently there are 840,000 part-time students in the system, representing 40 per cent of the total UK student cohort. Yet HE institutions describe part-time students as the Cinderella sector of HE, overlooked and under-funded. The independent review must look carefully at part-time students. Who are they and how is the current funding regime impacting upon them? How do we continue to attract part time students into the system?

The government has paid lip service to part- time students. In the summer the new Secretary of State for DIUS, John Denham, announced that he wanted to see an expansion in the number of part-time students, with more evening and weekend courses, in order to widen participation in higher education.

But just weeks later, his first big move in his new position was to announce a £100 million cut in HE funding for people taking a second qualification at the same level or below their first. This is a retrograde move that will harm part-time students more than anyone else. The Open University, which came joint top for student satisfaction in the National Student Survey again this year, has one third of students taking a second qualification and stands to lose more than £30 million of its funding. The Government is already in retreat and keeps on adding to the list of exempted subjects. It now remains to be seen whether their £100m figure will even add up.

Helmut Kohl used to fret that Germany found itself with the oldest students and the youngest pensioners in the world. No one wants to foster a higher education system filled with eternal students using university as a means of avoiding the wider world. However, by cutting second degrees the government has removed people’s right to change direction, and trampled upon their desire to broaden their skills. They are saying ‘no’ to the doctor who wants to study philosophy in order to work in the increasingly important field of medical ethics. They are saying ‘no’ to the history graduate who has thought long and hard and wants to retrain in IT. They are saying ‘no’ to anyone who needs to change direction. The message seems to be, if at first you don’t succeed, you don’t succeed.

In an ideal world, employers might step in and provide the funding for their employees. But what if the employee’s new direction does not fit with their agenda? And, as a recent report by UUK on part-time students showed, the reality is that the part-time students who get support from employers tend to be men in full-time employment from the wealthiest households. This policy penalises those trying to climb back onto the learning ladder most in need of public support.

We need to have a high-skilled workforce and we need an open education system to encourage an open society and social mobility. The debate on fees cuts straight to the heart of both of these issues. It is simply too important an issue for us to fly blind. A review of where we are now, focusing on the impact of the new fees on the mission to widen access to universities, on part-time and mature students, and on the financial health of our institutions, will set the stage for much clearer decision-making when the issue becomes live again in 2010.

The Student Experience

Yet students and their parents are not simply concerned about the cost of higher education. They care about quality. Students now regard themselves as customers, and they want to know that they are investing in the right student experience. If we are going to maintain that students should pay top-up fees – either at today’s level or a different one – then parents and students will have the right to demand that their fees are contributing to the delivery of a higher quality higher education experience. Rather than relying on clumsy monitoring institutions like the QAA, we can hold universities to account by empowering students with information about their courses.

Already we are seeing a rash of student websites springing up monitoring the ‘real’ experience at their university. RateMyProf.com, the anonymous ratings website that has been unsettling academics in the US since 1999, has now launched a UK version. It has been joined by others that strike equal fear into university administrations, including, “WillISeeMyTutor.com’. Increasingly students are picking up their placards and raising their voices in defence of their teaching provision. Parents and students at Exeter University set up a vociferous campaign about the axeing of the chemistry department, and history students at Bristol went railing to the press last year about when their contact time was cut to two hours a week. Angry students told the media that they thought they were paying fees to be educated by renowned academics, not to receive “library membership and a reading list”.

Whatever their content, these campaigns underline a demand for new information about universities, beyond what is available in the standard glossy marketing prospectuses. We need more transparency about what is really on offer to students.

The introduction of the National Student Survey, which surveys the quality of teaching, assessment and management of different courses across institutions, was a step in the right direction. There are already signs that vice chancellors are reacting to poor scores in areas such as feedback and assessment and striving to drive up their standards in a competitive market. However, there are also strong signs that this is yet another Gordon Brown target that can be gamed.

Do you want to make sure the students at your university sound satisfied? As one vice chancellor told me recently, there are ways and means. Do not go too hard on your students or organise early morning starts too close to survey time. Certainly never send out bills or reminder letters before you send out the survey form. If a lecturer has something terse to say to a student, he must never say it when the student is about to focus on filling in the survey – bide your time for the best results!

The National Student Survey has its uses, but it should not be the last word on the student experience. Clearly we need new methods of monitoring and maintaining quality. We should ensure that there is much more data in the public domain. We will put pressure upon universities to provide information that is currently kept hidden – but which the public would like to see.

I believe there is a strong argument for an official website which students and parents can search for much more detailed information about universities and courses. Such a site would empower students and their parents, giving them a much clearer picture of what different institutions offer and what they can expect from their time at university. It would also provide an important benchmarking system for universities and colleges, highlighting areas they could build on in order to improve the quality of their student experience.

The government has set up a number of little-known sites along these lines – the latest of which has yet to launch despite promises it would be up in September – seems to offer no big step forward in terms of useful new data.

It is becoming more and more common for parents to bemoan the fact that they are paying thousands of pounds for their children to go to university, despite the fact that they only shows their face in the faculty building for a few hours each week. To some extent it has always been thus. A university experience is about independent learning, and a move away from the comfortable spoon-fed environment of school, with plenty of time to think and research.

However, there needs to be a national student experience website would pull together searchable information on research ratings, drop-out rates, library facilities and university estates. This is all in the public domain already, but hard to find unless you are an expert on HE statistics.

But more importantly, universities must be urged to provide some data that is not in the public domain.

In particular students and parents want information on contact hours, class sizes and employability. Universities have resisted making such information available, but as a market emerges in higher education and as students become increasingly savvy about the investment they are making, we will need more transparency.

The institutions rightly point out that any such information is imperfect. It focuses on inputs, not outputs. A powerful lecturer may be able to teach 200 students as easily as 50. And universities are not the same as schools. However, I do not think we should not be using it as an excuse not to collect or release. A survey of first-year students by the Higher Education Academy found that 41% of students who knew nothing about their course before they enrolled had considered dropping out, compared with only 25% of students who knew a moderate amount or a lot about what to expect from their course. Transparency will not only drive up quality, it will help with the management of expectations.

Similarly information about class sizes is kept very quiet. We want to bring it out into the open, searchable on the national student experience website by course and institution. Worryingly, academics from all sorts of universities (including the Russell group) report that as institutions expand, their class sizes are spiralling. A frustrated psychology professor at a leading research university told me recently that his final year classes had ballooned from 16 students to around 200. He felt that his students were getting a raw deal at the very time when their study should be reaching its peak.

Such big increases can be explained by two factors. First, the major expansion of student numbers, which has been an overwhelmingly good thing, has nonetheless stretched university resources to the limits. Secondly, the emphasis on securing research grants above all else has resulted in an inevitable pull away from teaching, with professors filling in grant applications while PhD students stand in front of lecterns. These are complicated long-term issues upon which I want to reflect with the sector. However, in our rush to grow our higher education system, and to develop our universities, we must not lose sight of what it is we are trying to deliver with a university education. The old question, “What is a university for?” has perhaps never been more relevant.

The national student experience website would bring together new information on employability. There is clear evidence that having a degree enhances both one’s earning potential and one’s ability to secure a job. Yet it is much trickier to find data on job prospects for graduates from individual institutions. This matters. Students are more focused on the job market than ever before. Gone are the days when they went away to university primarily to boost their social lives, or even to continue acquiring knowledge for its own sake. More than 7 in 10 students go to university in order to improve their job prospects, and 60% want to boost their earning potential. Students may want to know how their subject will be taught, but ultimately they want to know whether it will hoist them onto the career ladder.

That said we must not forget that university should be about much more than simply securing a qualification that will lead to a job. University should be an enriching life experience, and institutions should fit students not just for the workplace but also for society.

Student Unions

The student is not just a free-floating consumer. He is a member of a community. To this end, we should strive to foster the idea of the university community. Each and every university is its own community – its own society. Whether it be a leafy out-of-town campus, or spread across the centre of London, every university, and every student body, has its own collective feel, challenges, successes, character.

But the hub of these university communities is not the university itself. It is not the Vice Chancellor, the central administration or the quadrangle. It is the students’ union.

Many of these determined and commercially attractive institutions form such a successful hub that they have been the envy of their respective university administrations. Recognising their potential some universities have made advances on the services their students’ union provides.

Universities – and, for that matter, FE colleges too – should not just be places where you drive in, turn up for a lesson and then drive off at the end of class. They should be open communities which welcome and encourage learners. I think it is sad that almost half of students now do most or all of their socialising outside the university.

This is not the way forward. In an age where the voluntary sector helps to run the New Deal, it cannot be progressive to let universities encroach upon their own voluntary sector. If we take a closer look at today’s students’ unions, it becomes fundamentally apparent that the student experience and wider society can only benefit from their continued independence from university and state control.

Student unions are often viewed by wider society as the place where Marxist-Leninists have hard-fought ideological battles with Leninist-Marxists. There are still some union members who use them as an opportunity to posture. There are new threats as well; radical Islam has emerged on some of our campuses – and student unions cannot be expected to deal with it on their own. However, this is not typical. These days, students are more likely to have posters of Boris Johnson than Che Guevara. The social interaction and fiery political debate that went on when I was an undergraduate was – and still is – important. But students’ unions offer so much more to students and to the communities they live in.

Welfare and advice services provided by students, for students, are at the heart of what student unions have to offer. And whilst many of these services, such as Nottingham’s sexual health or Reading’s immigration advice, are provided by government or university departments, students would often prefer to approach their peers about their problems rather than the sate or other authority.

Should these services not have been there, who knows how many students would have kept their problems to themselves, having been too mistrustful of university or state authority. For example, international students from countries with far more intrusive states than our own have been know to be too scared to approach a university-run welfare service or their personal tutor. But they would not fear a fellow student who they could speak to in confidence.

Participation in student societies is, nowadays, a feature of the ambitious graduate’s CV. Students’ unions nurture these societies, which, regardless of whether they seek to promote the Conservative Party (or to destroy it) all help students to learn vital skills for the workplace. These might include event organisation, financial management, public speaking, marketing, fundraising and even sales.

Furthermore, there are some careers where no involvement in students’ unions and their societies is a distinct disadvantage. The humble student newspaper, for example, has been a fertile breeding ground for Fleet Street and broadcast media for many years.

Out in the communities that surround our universities, student community action groups are bringing real benefit to the lives of others. Students’ unions are playing their part in their local communities: Charitable fundraising; university governance; sports and fitness training; examination guidance; job centres; equality campaigning. I could go on. The Party has recently rediscovered its commitment to social responsibility – or what I have called ‘Civic Conservatism’. It is an interest in institutions which help build a strong society. To local schools, hospitals, charities, friendly societies, I would add student unions.

We value student unions. We salute them and what they achieve for and on behalf of students. Without them, universities would be much poorer institutions, as would the employers, causes and political parties who take on their alumni.

Conclusion

We have a great tradition of higher education in the UK. As British universities expand, so they must become the gold standard for other universities to follow across the globe. As well as leading the world with our research we must continue to strive to offer the best and most rewarding experience for our students.

Higher education may have slipped down the political agenda since the tumultuous debate over top-up fees in 2004, with the government insisting this is a “bedding-in period” and no further discussion is needed. But higher education – for all who can benefit from it, regardless of social status, age or career – is a serious and pressing priority. We should not be wasting time now.