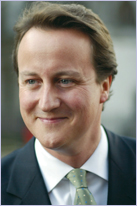

David Cameron – 2007 Speech on the Economy

Below is the text of the speech made by David Cameron, the then Leader of the Opposition, at the LSE on 10 September 2007.

INTRODUCTION – THE END OF ECONOMIC HISTORY?

When I studied economics, twenty years ago, arguments raged about the most basic principles of how to run the economy.

There may have been some agreement about aims: to save Britain from being the sick man of Europe, and raise living standards throughout the country.

But there was a vast gulf between left and right as to how this could best be achieved.

The left advocated more intervention and government ownership.

Those on the right argued for monetary discipline and free enterprise.

That debate is now settled.

Over the past fifteen years, governments across the world have put into practice the principles of monetary discipline and free enterprise.

The result?

A vast increase in global wealth.

The world economy more stable than for a generation.

Global income doubled.

Two billion people have escaped subsistence poverty, and joined the world economy.

So the conclusion appears…well, conclusive.

Francis Fukuyama argued in the early 1990s that, if we see human history as the acting-out of intellectual disputes, then history was over.

On the political battlefield, democracy had emerged the victor; in economics, liberalism had prevailed.

Thus in 1990 the “post-Cold War consensus” began: the idea that, as Fukuyama put it, history had ended in the triumph of liberal democracy and market economics.

Today, Fukuyama’s political thesis – the victory of liberal democracy – has been qualified, shall we say, by events since 2001.

And in this lecture I want to ask what has happened to his thesis in the economic sphere – the consensus on free markets.

Have we really seen the end of economic history?

AGREEMENT ON THE FUNDAMENTALS

Here in Britain, it is tempting to answer that the consensus is intact.

The principles put forward by Nigel Lawson in his 1984 Mais lecture have become standard practice:

Use macroeconomic policy to ensure stability and control inflation.

Use microeconomic policy to promote supply side growth.

Less intervention; more competition; an increasingly open economy.

Added to this, the monetary framework that we developed in the early 1990s – a combination of inflation targeting and a floating exchange rate – brought to an end decades of argument in Britain, and academic debate.

I’m proud that this is one of the few countries in the world where all serious candidates for high office support the principles of free trade and monetary discipline.Other countries – even America or Germany – have senior politicians who disagree with economic liberalism.

Not us.

Indeed the whole New Labour project was built on recognising, and accepting, the free market consensus.

When I visited India last year everyone – from the Prime Minister to the chief executive of Tata Steel – told me that Britain’s political consensus on free markets is one of our most important selling points as a destination for trade and investment.

So I will not exaggerate the differences between myself and Gordon Brown on the overall economic framework.

And yet my argument today is that we have in fact reached the limits of the post-Cold War consensus.

We have reached its limits because the post-Cold War consensus was actually a consensus on how to manage Cold War-era economies.

It does not provide answers to the questions that have emerged since 1990.

MARKET TURBULENCE

Of course, in many ways the times we have been living through in the past decade have been remarkably benign.

Indeed, the recent turbulence in the credit markets has reminded us of just that fact…

…as well as the reality that the very success of a competitive and innovative economy can lead to new challenges.

Our hugely sophisticated financial markets match funds with ideas better than ever before.

They have facilitated cheap credit that has helped companies expand, helped families achieve their dreams, and helped entrepreneurs put their ideas into practice.

Yet that same cheap credit has also increased the social problems associated with over-indebtedness, and potentially has made us more vulnerable to global shocks.

And it leaves central banks grappling with the question of whether providing help now will increase the danger in future.

It is still too soon to know what impact this latest bout of financial turbulence will have on the real economy of jobs and investment.

But it is clear that our economy has not been best prepared.

Gordon Brown’s reckless strategy of excessive borrowing, leaving our economy with the largest structural deficit in Europe, has left us ill-prepared to respond if the turbulence spreads more widely.

That is why we are determined to create a more secure framework for economic stability in this country.

In terms of monetary policy, by enhancing the independence of the Monetary Policy Committee.

And in fiscal policy, by giving control over monitoring of the fiscal rules to an independent body.

These measures will strengthen monetary policy, and ensure that fiscal policy supports rather than undermines it.

But while these differences on the execution of macroeconomic policy are important, they are not as great as the difference between the approaches of right and left on the big questions that will determine the course of economic history in this century.

Our distinct responses to these big questions about the future give the lie to the idea that we have reached the end of economic history.

There are three questions in particular that the modern world demands answers to – and I would like to address these questions today.

First, the best way to stimulate economic growth in the face of globalisation.

Second, the best way to stimulate green growth in the face of climate change.

And third, the best way to stimulate social growth in the face of inequality and social breakdown.

ECONOMIC GROWTH: SUPPLY SIDE REFORM

It is globalisation that most insistently prompts us to consider afresh the question of economic growth, and whether there really is consensus about the right way to stimulate that growth in the post-Cold War era.

History did not stop in 1990, any more than the church clock stopped at 10 to 3 one summer day in 1914.

John Maynard Keynes’ famous description of the pre-World War One Londoner, “sipping his morning tea in bed” and ordering by telephone “the various products of the whole earth” is famous because that world abruptly ended in the guns of August.

Many years of economic nationalism followed, until a new era of globalisation began in our own time.

So we must not assume, like Keynes’s Edwardian Londoner, that the age of Amazon, eBay and Google is here to stay forever.

The thousands of people who demonstrated against the WTO in Seattle, or against the G8 recently in Germany, certainly don’t think that globalisation is a necessary or inevitable process.

As George Osborne has put it, every generation has to make the case for free markets.

And every generation has to develop the mechanisms to make free markets work better.

Nearly two years ago I asked our economic competitiveness policy group to set out proposals for the way Britain should meet the challenges of globalisation.

Its findings were very clear.

To stimulate economic growth in the new global economy, dramatic supply side reform is required.

Government must regulate and tax enterprises less.

But Britain’s competitiveness is not simply a matter of government getting out of the way.

It must also do more to secure the skills, energy and transport infrastructure that help us compete.

For example, we need a radical simplification of business taxes, to lower the rate and broaden the base.

But we must also ensure that we remain at the cutting edge of science and technology.

Government funding of science and technology may look to some like old-fashioned interventionism.

Yet because the findings of primary research can be too far from the market to be commercially viable, there is a strong case for direct government intervention.

Some of the most successful free market economies, like the United States, spend the highest proportions of their income on government-funded scientific research.

Our taskforce on Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics has set out an ambitious agenda for promoting science and innovation…

…including proposals to promote scientific research in our universities, and make it easier for innovative start-up businesses to win government contracts.

While we bring forward supply-side reform proposals that are imaginative and appropriate to the scale of the challenges we face, the Labour government is in my view moving in the wrong direction.

And so I do not believe there is consensus on the best way to stimulate economic growth in Britain today.

Our economy is labouring under the highest tax burden in our peacetime history, the longest tax code in the world, and an explosion of new regulations that cost us more than £50 billion a year.

Just last week we heard that the latest version of Tolley’s tax handbook is more than twice as long as it was in 1997.

The publishers even had to change the formatting just to stop it going to five volumes.

The result of all this is that Britain has fallen from 4th to 10th in league tables of economic competitiveness.

Indeed, last week the Institute of Directors concluded from its annual survey that Britain’s competitiveness was “remarkable by its mediocrity.”

This is not an abstract concern.

Research done here at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance shows that on average a British worker has to work an extra day each week, just to produce the same as an equivalent worker in France.

Our average rate of productivity growth – what Gordon Brown himself has called the “fundamental yardstick” of economic performance – has actually fallen over the last decade.

Meanwhile in America it has almost doubled.

Both a symptom and a cause of Britain’s falling overall productivity is the productivity of our public services, for which the Government is responsible.

Perhaps the biggest mystery in British politics is how Labour can have spent so much and achieved so little.

I believe the answer is a top-down system of central control and targets that takes power away from the professionals who deliver public services and the citizens who use them.

And at the centre of it all a Treasury that, under Gordon Brown, was so busy trying to do everything that it lost sight of its single most important role – delivering value for money.

We believe that it’s time for change…that it’s time for modern Conservative supply-side reform to stimulate higher economic growth.

The agenda is clear.

We need deregulation to promote commercial competitiveness.

We need decentralisation to promote public sector productivity.

And overall, we need to share the proceeds of economic growth between higher investment in our public services and lower taxes.

George Osborne and I have made clear that we will put economic stability before promises of up-front, un-funded tax cuts.

As George Osborne has set out, we will match Labour’s spending totals, and by growing the economy more quickly than public spending over an economic cycle, we will deliver a lower tax economy over time.

Sharing the proceeds of growth is a significant policy choice.

There are clear dividing lines here, and I believe that in time economic history will show that once again those on the political right, and not those on the left, have the correct analysis and the most productive policy solutions.

GREEN GROWTH: MARKETS AND GREEN TAXES

Just as the pressing need for supply-side reform in the face of globalisation should enable us to challenge the notion of a post-Cold War consensus on economic growth…

…and the accompanying fiction that we have reached the end of economic history…

…the threat of imminent, irreversible, and catastrophic change to the climate of our planet should prompt us to challenge any perceived consensus on green growth…

…the vital need to protect our environment through policy that enhances, rather than impedes, wealth creation.

I won’t rehearse here the arguments in favour of action to halt climate change.

Let me simply ask the big question to which economics must provide a modern answer:

How can we make economic growth sustainable for our planet?

This is not a question many people were asking at the end of the Cold War, but they are certainly asking it now.

The pollution that leads to global warming is one of the greatest market failures of all time.

Some argue that to save the planet we must stop growing altogether.

Capitalism has brought this threat upon us, they say, and we must reduce consumption now.

Others argue that whether or not climate change is man-made, there is nothing we can realistically do to stop it, so we should simply prepare for the consequences.

I think both are wrong.

As Nicholas Stern’s authoritative report showed, the likely economic cost of inaction is greater than the cost of action.

So what is the action we need to take?

I believe that if we blame capitalism for climate change, we should also look to capitalism for the solution.

Jonathan Porritt, in his important book Capitalism as if the world matters, argues explicitly that we must harness the power of the market to deliver progress on the environment.

Of course we must look at all the tools at our disposal, including green taxes, trading, regulation and technology.

But in designing and using those tools, we must understand their limitations.

Consider for example the choice between green taxes and carbon trading.

In theory, the argument for trading schemes is compelling.

Government sets the limit, and the market puts a price on carbon.

The result is that carbon is reduced at the lowest marginal cost.

But a growing body of evidence shows that the reality can be very different.

Consider the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, the largest scheme of its kind.

Partly due to government backsliding on national emissions quotas, the first phase of the scheme has suffered from low and variable carbon prices that have failed to provide the long term incentives needed to affect investment decisions.

I support the scheme and I hope that the second and third phases will be more successful.

But time is running out.

More generally, trading schemes may seem the obvious free market solution, based as they are on market transactions.

But crucially they are artificial markets dependent on government regulation and monitoring for their existence.

A growing strand of opinion on the right argues that green taxes provide both better environmental outcomes and make more economic sense.

In a paper for the free market think tank the American Enterprise Institute, Kenneth Green and others have gone so far as to argue that because of the cost in terms of bureaucracy, the opportunities for fraud, and the inherent incentive “to push the legality at all stages of the process”, carbon trading systems are bound to suffer limitations.

Instead, they argue for environmental tax reform.

I believe that to confront the challenge of climate change and to stimulate the green growth we need, we must use a combination of the tools available to us.

Trading schemes will play an important role, but they depend crucially on real government leadership in setting quotas and ensuring they are kept to.

Environmental taxes must also play a role.

As taxes will always have an incentive effect – discouraging whatever they are levied on – why not use them to discourage bad things rather than good things?

To mitigate market failure, rather than pervert good decision-making?

Environmental tax reform can have economic benefits too – the so called “double dividend” of lower pollution and lower taxes on jobs and investment.

But in this country, that is not what we have seen.

By using green taxes as extra stealth taxes, Gordon Brown has given them a bad name.

I’m determined that the Conservative approach will be different.

With my Government, any new green taxes will be replacement taxes, not new stealth taxes.

In a few days, our Quality of Life Policy Group will publish its report.

It will contain many recommendations on tackling climate change, at home and abroad, including recommendations on green taxes.

As with all the reports in our Policy Review, we will study its proposals carefully.

But let me be clear.

We will raise green taxes, and use the proceeds to reduce taxes elsewhere.

That is the right direction for the environment and it’s the right direction for our economy.

It is the best way to deliver the green growth that must be our aim.

SOCIAL GROWTH: INEQUALITY AND WELL-BEING

Let me turn now to the last great counter-argument to the post Cold War consensus.

The case for the end of economic history is based on the observation that everyone now agrees on the need for economic growth and the way to achieve it – even if sometimes they don’t always practice what they preach.

But there is an area of profound disagreement beyond this consensus.

It concerns the need to stimulate the social growth that people demand in the face of inequality and social breakdown.

How shall we help, firstly, those left behind by economic growth – and secondly, those for whom economic growth is not enough?

This matters, for the simple reason that everyone is in one or other of these groups.

First let me talk about those left behind.

If we are to enjoy all the potential benefits of the modern economic era, we need to understand why so many people are deeply anxious about it.

For a start, we have to be honest and admit that when the winds of globalisation are unleashed, our societies become more prosperous overall but people can get left behind.

There are towns in Britain where the retreat of traditional industries has helped to leave a quarter of older working men on disability benefit year after year.

Where the winds of globalisation feel like a chilling blast, not an invigorating breeze.

As is often pointed out, globalisation tends to decrease inequalities between countries, but it can also increase inequalities within countries.

So we should celebrate the benefits of globalisation.

But we must also recognise our moral obligation to the people and the places left behind.

For government that means preparing our economy to make the most of globalisation, and preparing our society to cope with the disruption it can bring.

The tragedy is that for all their rhetoric – and for all their undoubted sincerity and effort – our present Labour government has failed in these vital tasks.

I have already noted Labour’s economic failure, in particular with respect to supply-side reform.

This is a record that is, I think, increasingly well-understood in the economics community and beyond.

Perhaps less well understood is Labour’s failure to prepare our society.

Too many people in our country are not sharing in the new global prosperity.

There is a poverty of ambition, of capability, and of hope – increasingly passed down through generations – which the world’s rising prosperity has failed to dent.

It is a startling fact that despite the vast rises in wealth across the world, in Britain, the poorest in our society have got poorer in the past ten years.

Social mobility is falling.

Some estates in Britain have a lower life expectancy than the Gaza Strip.

But the old solutions are not working.

Over the past decade the degree of redistribution between regions of the UK has reached unprecedented levels.

Yet still, as the IPPR has demonstrated, regional inequality has actually risen.

They warn that the north-east remains at the lower end of achievement in education, health and welfare-to-work despite receiving some of England’s highest total spending on public services per head over the last decade.

And of course it is not just inequality between regions that is growing, but inequality between communities and people within regions.

Areas of entrenched poverty sit alongside pockets of vast wealth.

We have known for years that the old responses of the old left – hostility to markets and enterprise – were spectacularly ill-suited to the task of overcoming these challenges.

But now we can see that the new responses of the new left – targets and transfers – have failed too.

Child poverty is rising, despite a huge increase in means-tested benefits.

On Government figures, 600,000 more people are in extreme poverty than in 1997.

Massive payments from one region to another have not halted the growing disparity.

It is clear that social growth – enabling everyone to share in growing global prosperity – requires new solutions.

We know that high taxation and over-regulation can stifle the enterprising spirit.

We know that without a decent education, success is ever harder.

And we know that the greatest force for social progress is the force of people’s determination to build a better life for themselves and their family.

So let us take those lessons and apply them across Britain.

Our approach reflects the modern Conservative freedom agenda, aiming to give people more power and control over their lives…an approach built around enterprise, education and aspiration.

Enterprise – where we learn from countries where radical benefits reform, with tough incentives combined with patient, personalised support from the voluntary sector, has moved people from welfare to work.

Education – where we learn from countries where radical schools reform, enabling the creation of new schools that give parents a real choice within the state sector, has helped increase standards, discipline and achievement – particularly in poor neighbourhoods

And aspiration – where we understand that none of this will work without a renewed drive to create a can-do culture of opportunity.

Over the past year, across Britain the average family has seen their take home pay actually fall in real terms.

Thanks to a rising cost of living and extra stealth taxes, families are finding their budgets increasingly squeezed.

And when young families look to take their first steps onto the housing ladder, they find that even the bottom rung is unattainable.

Half of all families now rely on their parents for help in buying their first home.

Yet because the threshold has not kept up with the rise in house prices, more than a third of families now find that aspiration hampered as they fall into the inheritance tax net.

There are so many ways in which those striving to reach their aspirations for a decent life are being hit.

Because of the complex tax and benefits system, millions of people on low and middle incomes find that if they earn a little extra, or move from part time to full time work, the taxman takes away more than two thirds of every extra pound they earn.

So any revenue raised from new green taxes will be used to reduce the burden on those striving hard for a better life.

WELL-BEING

I grew up in a home that was materially privileged.

But as I have often said, the real privilege of my upbringing was a strong family.

And that is the point I want to end on today.

If a significant, unacceptably large minority of our fellow countrymen and women are trapped in poverty, in all the horrors of multiple deprivation and social injustice, the majority of us are also trapped in an economic system which can be destructive of family and community life – destructive of all the elements which contribute to well-being.

Let me explain clearly what I mean when I talk about well-being.

I do not mean some woolly, new-age, anti-capitalist agenda which favours downshifting rather than ambition, or a hair-shirt Puritanism rather than the legitimate pursuit of happiness.

Capitalism is clearly the greatest agent of human fulfilment that human ingenuity has ever contrived.

But capitalism on its own is not enough: an approach that ignores the rest of life is one that is badly misguided.

For me, well-being is simply the opposite of the social breakdown that we see all around us in countless daily manifestations…

…crime and anti-social behaviour, rudeness and incivility, litter on the streets and a transport system which makes it such a hassle to get around.

For me, well-being means a determination to improve the quality of life for everyone in our country.

Let me demonstrate my point with a quotation I am fond of from Robert Kennedy:

“Our gross national product… if we should judge America by that – counts air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage.

It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for those who break them.

It counts napalm and the cost of a nuclear warhead, and armored cars for police who fight riots in our streets.

It counts Whitman’s rifle and Speck’s knife, and the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children.

Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play.

It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages; the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials.

It measures neither our wit nor our courage; neither our wisdom nor our learning; neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country; it measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”

Those words have a special relevance for Britain today.

Over the last ten years we have fallen in the league tables of quality of life.

For example, the UN’s Human Development Index, devised by Amartya Sen and Mahbub ul Haq, found that quality of life in the UK has fallen from 10th in the world a decade ago to 18th in the world today.

That is a terrible finding.

How do we increase well-being alongside wealth?

How do we stimulate the social growth that people so badly want?

Economists are now fully engaged in this debate.

On one side of the argument, Lord Layard has pointed out that once out of poverty, happiness doesn’t seem to rise with income, and more equal societies are happier.

From this he draws a simple policy conclusion: more redistribution is needed.

Yet this simple analysis only gives part of the picture.

Recent work by Paul Ormerod and Helen Johns shows that redistribution does not increase happiness either.

In fact, as Ormerod and Johns show, the few things that do consistently correlate with well-being are the sense of trustfulness in the society we live in, our health, and the strength of our marriages.

And this points me to a central insight of Conservatism – central to the Conservative philosophy throughout our Party’s history.

The value of institutions.

Abstract national wealth – a high rate of GDP – is necessary, but not sufficient, to deliver higher GWB, or general well-being.

We need to tackle poverty, and we need to tackle inequality – particularly the gap between the mainstream and those left behind.

But we need more than that.

We need above all an agenda which puts not the individual, not the state, but society at the centre of national life:

… society in all its forms: families and local councils, trade unions and churches, small shops and great universities, charities and clubs and protest groups …

…all the institutions and associations that in Bobby Kennedy’s words, “make life worthwhile.”

That’s what I call a richer society.

That, to me, is the real object of economic policy.

CONCLUSION

So far from this being the end of economic history, far from there being a consensus on economic matters today…

I believe there are still great battles to fight.

But these are different battles, on different terrain.

The fight for supply-side reform that will deliver economic growth in the face of globalisation.

The fight for environmental protection that will deliver green growth in the face of climate change.

And the fight for well-being that will deliver social growth in the face of inequality and social breakdown.

Economic growth; green growth; social growth.

These are the big questions in the economic debates of the modern age.

This is the new economic history that it falls to this generation to write.

And these are the battles that the centre-right of politics is once again uniquely equipped to fight.