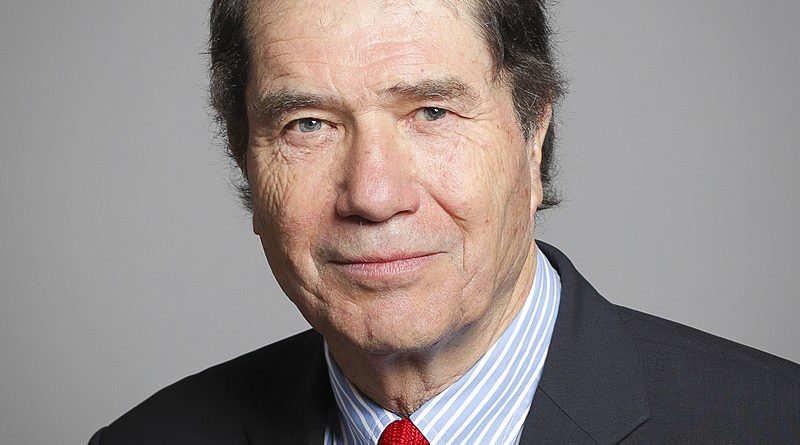

Michael Berkeley – 2022 Tribute to HM Queen Elizabeth II (Baron Berkeley of Knighton)

The tribute made by Michael Berkeley, Baron Berkeley of Knighton, in the House of Lords on 10 September 2022.

My Lords, I will talk about music, but will concentrate largely on animals, which were so loved by our late Queen, as we have already heard from all around your Lordships’ House. It is a great honour and privilege to be able to pay tribute to such a much-loved monarch.

I was fortunate to serve on the committee for the Queen’s Medal for Music and repeatedly saw how the Queen embraced nervous recipients and talked at length, putting them at ease and making them feel comfortable. They were all charmed. On one occasion, sitting next to Her Majesty during a fiendishly difficult piano piece with fistfuls of notes, we remarked how three hands would really be useful. The soloist departed, came back to take a bow and stumbled as she came on to the stage. There followed the observation: “Three feet would be good too.”

From three feet, to four: the royal corgis, of which we have heard much—they would expect nothing less—were always put to dutiful use. We have heard examples of it. It is quite a clever use of these animals. I make no excuse for repeating a story some noble Lords will already have heard. On my BBC Radio 3 programme, “Private Passions” and in his book, the war surgeon David Nott recalled how, returning from Syria and in a state of terrible post-traumatic stress, he was placed next to the Queen at a lunch at Buckingham Palace.

Her Majesty said, “Tell me about things in Aleppo now.” David was in such a completely paralysed state that he found himself unable to speak. Sensing his hurt, the insightful monarch summoned a footman to fetch the biscuit tin. She passed the tin to David, who, momentarily, in his confusion, thought this was a royal command to eat one of the dog biscuits. He then realised that he was being invited to feed the aforementioned quadrupeds. As, now distracted, he did so, the Queen touched his hand, saying, “Now, that’s better, isn’t it?” Her Majesty had, through her insight, rescued and relaxed him and set free his tongue.

The Queen had a much-loved red Labrador called Sandringham Sydney. As chairman of the Royal Ballet governors, I had to write an annual report to our royal patron. I could not resist naughtily adding a handwritten postscript:

“On another matter, arguably of less national importance, I have a red descendant of Sandringham Sydney who has produced puppies and my brother-in-law is so besotted with his puppy that he dreamed he put him down for Eton.”

I had two letters back. One rather formally acknowledged the Royal Ballet report, but the other was clearly revelling in the concept of putting a dog down for Eton. I loved the idea that my missive was replied to with two compartmentalised communications—the formal and the humorously canine. From then on, whenever I met Her Majesty, the problems of preserving and continuing that red colour through the work of the Sandringham kennelman would be a welcome byway from the usual niceties of retrograde inversion and music that perhaps were a little difficult to comprehend on occasion.

Let us move on to another favoured creature. It is a great sadness to me personally that my brother-in-law, Michael Bond, did not live to see Paddington Bear—his creation—charm the nation and Her Majesty. Was not that sequence a wonderful example of the great sense of fun that Her Majesty had? Her sense of mischief and delight in the absurd, which she bequeathed to her children, underlined her ability to connect with people and laugh at the unforeseen.

Finally, has not the Queen somehow continued her benevolent influence, as parliamentarians here and in the other place have, in my humble opinion, risen above themselves to make such eloquent and moving tributes? So too did our new King, Charles III, passionately. Long live the King.