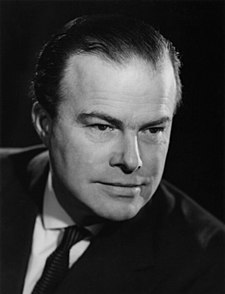

David Gibson-Watt – 1967 Speech on Aberfan Inquiry

The speech made by David Gibson-Watt, the then Conservative MP for Hereford, in the House of Commons on 26 October 1967.

I am sure that the House will be grateful to the Secretary of State for the very sympathetic way in which he has dealt with this very difficult subject, for 21st October, 1966, will certainly rank as one of the grimmest days in Welsh history. It is not the first time that a mining community has suffered, for mining is a hard and dangerous calling, but it is the first time in the long history of the mining industry that the young have had to suffer.

Anyone who knows the valleys of Wales will agree that they have a special character. They are close communities. The valley which contains the two villages of Aberfan and Merthyr Vale has a community that is especially close, for a great proportion of the men employed there are employed in the Merthyr Vale Colliery. Mining, with all its hazards, creates a particular fraternity among those men, and this closeness was certainly never shown to better advantage than in the awful moments that followed the fatal disaster in October last year.

Whatever we say today in this debate, we should bear in mind that our main objective is to heal and to give strength to these people, and we should honour those who have suffered and not add to their suffering.

We would all wish to pay tribute to the many who helped after the disaster—the many volunteers spearheaded, of course, by the miners themselves; to the police, the Civil Defence, the ambulance and nursing services and other public bodies, the many voluntary services and organisations and, indeed, to the troops who came in later. Nor should the Welsh Office be without its share of credit, as my right hon. Friend the Leader of the Opposition said in the House some days after the disaster.

The administrative job, as the Secretary of State has said, was complicated by two factors: first, Aberfan falls under two authorities—Glamorgan and Merthyr Tydvil; secondly, the vast number of people who flocked to Aberfan on that day, some to gaze helplessly but many more to dig and to work. I myself, like other Members of the House, saw dozens of young volunteers going in their cars with equipment, only to be turned away, so great was the crush within the valley. Considering these two problems—the duplication of administration and the crowds who flocked there—the rescue and the clearance work was certainly very well done.

I would ask the Minister whether the aftermath of this disaster has perhaps changed some of the thinking in the Home Office on this matter. I also ask this question: on such an occasion, who should be in charge—a Minister, a mayor, a policeman or a Civil Defence officer. I think perhaps more guidance might be given on this point from the Home Office in case of any trouble in the future.

The Tribunal set up by the Secretary of State for Wales was, as the right hon. Gentleman said, composed of three well-known men, and was under the chairmanship of Sir Edmund Davies, a Lord Justice of Appeal, a popular man who was born and bred in the valleys. It is clear that they carried out their unpleasant and difficult task with sympathy and competence, and, indeed patience, for this Tribunal went on for an unnecessarily long time.

The Tribunal’s Report is clear. It is detailed and it makes recommendations to help the avoidance of future such disasters. On page 131 is the summary of its findings. The first finding is: Blame for the disaster rests upon the National Coal Board. The reasons for its findings are detailed in the Report, and the men whom the Tribunal describe as not being without blame have been named. I do not intend to pursue this. It is a heavy punishment indeed to be named by a tribunal of this sort.

But what a tale this Tribunal unfolded. It is a sombre catalogue of incompetence, subterfuge and failure, of warnings disregarded, a complete exposure of the lack of communication within the National Coal Board. It must seem incredible to anybody who reads this Report that Tip No. 7 on Merthyr Mountain should ever have been chosen and that it should have been tipped on for so long, when the water problems was abundantly clear, when the tailings problem was admitted and when there were so many complaints about Tip No. 7.

Complaints came from several organisations, including the Merthyr Corporation, many individuals and, in particular, Councillor Mrs. Williams, whose strong complaint in the Merthyr Planning Committee was reported in the Merthyr Express in 1964. She said: If the tip moved it could threaten the whole school. The complaints were frequent.

Let me quote but two from the Merthyr Corporation. They started in July, 1959, as we are told on page 52 of the Report. Letters from the Borough Engineer, Mr. Jones, in 1963, referred to apprehensions about the movement of slurry to the danger and detriment of people and property adjoining the site of the tips. The Deputy Borough Engineer, Mr. Bradley, in 1963, wrote a number of letters which were headed Danger from coal slurry being tipped at the rear of the Pantglas Schools. To all these complaints the National Coal Board turned a deaf ear. It went on tipping. I cannot entertain the suggestion that the Merthyr Corporation can be held responsible in any way, nor, indeed could the Tribunal. As Mr. Alun Davies, Q.C., said at the Tribunal: …perhaps the natural mistake made by the Merthyr Corporation was that it accepted the opinions of the experts of this organisation at their own valuation. Little did the Corporation realise how empty were the assurances given by their experts, but in my submission this cannot be blameworthy conduct as between responsible men. To the several complaints from the Merthyr Corporation the answer was given by the National Coal Board that experts were being used. In 1950, the Coal Board wrote to the borough engineer saying that the Board was constantly checking the position of all these tips. In fact, it blinded them with science.

Alderman Tudor, himself an important witness, who gave considerable warnings to the Coal Board, said to the Tribunal: Remember, I was a layman with limited knowledge of tips. I had raised the matter of tips in the Consultative Committee and I was compelled to accept what Mr. Wynne told me, recognising that he had far more ability than had. And I thought that he was capable enough of making a decision. If he was not capable enough of making a decision, well then, he should have called someone else in. As a layman I could not argue with him, because he could have blinded me, because he knew more of the pits and he knew more of the pit work than I did. The Coal Board blinded them all. It was deaf to all warnings, written and vocal. It was blind, also, to the visual warnings. There has been tip slips on Mynydd Merthyr, which could all have been seen by those in charge. In 1944 a rotational slip on tip 4 was followed by a flow slide; between 1947 and 1951 a rotational slip on Tip No. 5; in 1963 a rotational slide on Tip No. 7 followed by a flow slide. Between 1964 and October, 1966 there were further slipping movements on Tip No. 7. There were also the other tip slides at Tymawr and Cilfynydd, from the neighbouring valleys.

Yet something stopped these men taking action. Something stopped them concentrating on this tip about which they were constantly warned. What was it? Was it just a combination of ignorance and failure to take responsibility? Was it the pressure of other work at the pit itself and in the rest of the area? Was it the fear that, if they stopped tipping on Tip No. 7, there was very little other land to tip on and the pit itself might be in danger of closure?

The evidence of the hon. Member for Merthyr Tydvil (Mr. S. O. Davies) reflects this question, but the Tribunal, in investigating it, did not find sufficient evidence to support it. Or was it the same attitude which any of us could have taken, an attitude which exists in the minds of those who live below a volcano and which may be epitomised in just a few words—”It will never happen”?

The Tribunal just blames the National Coal Board and says that there was an absence of tipping policy and no legislation dealing with tip safety. Although the Tribunal found blame for the disaster to rest with the Coal Board, it took a long time for the Coal Board to admit it. At the beginning, its statement gave no hint of acceptance at any level of any degree of blame for the disaster. Indeed, the Board’s counsel said: The Board’s view is that the disaster was due to a coincidence of a set of geological factors, each of which in itself is not exceptional but which collectively created a particularly critical geological environment”. Those words were later shown to be false, for, on the 65th day of the hearing, the Tribunal heard Mr. Piggott, the Board’s expert, say that the only exceptional feature about Merthyr Mountain lay in the fact that it had been used as a tipping site at all. Mr. Sheppard, the Director-General of Production of the National Coal Board, said in answer to Mr. Wien, the Board’s counsel, All the geological features could have been previously appreciated”. There was, in fact, a definite and continued attempt, in the view of the Tribunal, by the Coal Board to avoid responsibility.

Lord Robens’ original statement and his evidence did not make things any easier. After he had been to Aberfan, Lord Robens told a reporter: It was impossible to know that there was a spring in the heart of this tip which was turning the centre of the mountain into sludge”. Clearly, this was inaccurate, and it was said without technical advice. The evidence which Lord Robens gave to the Tribunal later was self-contradictory and inconsistent, so much so that counsel for the N.C.B., in his closing address, said that it had not assisted the Tribunal and asked that it be disregarded.

Lord Robens was in a difficulty. He must, like anyone connected with this matter, have been in a state of mental turmoil. He made his inaccurate statement to the television reporter before he had been able to get proper advice. But, surely, he must afterwards have known what the Coal Board’s line was to be before the Tribunal, after that statement and before the Tribunal had met.

Lord Robens said in his evidence—this is recorded on page 91 of the Report —that by the time the inquiry started on 29th November he was satisfied that the causes were reasonably foreseeable. If that was so, why did the Coal Board persist in its attitude until day 65, when Mr. Piggott, the Board’s expert, finally said: All the geological features could have been previously appreciated”? This is not easy to understand. It is easy, as the Tribunal said, for anyone to be guilty of hindsight. It is easy for us to criticise and to accuse with the Report before us. But it is not easy to understand Lord Robens’ attitude from the time of the disaster to the end of the Tribunal. Blame for the disaster rests with the Coal Board. That is the Tribunal’s first finding, and, as the Secretary of State said, certain officials of the Coal Board have been moved within the Board’s organisation.

Lord Robens offered his resignation to the Minister. It was certainly the honourable thing for him to do, as head of this vast industrial empire which was blamed for the disaster by the Tribunal. The Minister has refused to accept his resignation. I ask the Minister today to say a little more about his reasons for not accepting it. The only point in the Secretary of State’s speech in which I did not fully concur was when he said that the Minister had given his reasons. The copies of the letters passing between the chairman of the National Coal Board and the Minister do not give us the reasons.

In his letter to Lord Robens rejecting his resignation, the right hon. Gentleman said: Nor do I consider that the conclusions of the Tribunal are of a kind which call for your resignation. The conclusions of the Tribunal were that the Coal Board was totally responsible for the disaster. The evidence of Lord Robens was not only late, but it was found to be useless by the Coal Board’s counsel, so much so that, as I have said, he asked for it to be disregarded. I cannot help saying to the Minister that I am sure he has further reasons for refusing Lord Robens’ resignation, and from our side we should very much like to hear them. I repeat that we are not asking that Lord Robens should resign. We want only to be told more about the Minister’s reasons.

The right hon. Gentleman may say that Lord Robens’ leadership is essential to the Coal Board in the difficulties which the industry faces, and with this we could agree. It is a complicated industry. In Wales alone, just under 60,000 men are still employed in just over 70 collieries. Lord Robens has done much to restore morale within the mining industry.

I put these questions to the Minister. How much does this huge industry decentralise? How much more will it decentralise now, since the study which, we are told, has taken place? How much responsibility did the divisions take in the past? I ask this question because, in all the evidence which was brought before the Tribunal, there was one person who was not called by counsel for the Coal Board. I find it curious that Mr. Kellett, the Chairman of the South-Western Division, was not called to give evidence regarding a pit disaster which occurred within his division. I hope that the Minister will be able to answer that tonight.

The Minister of Power (Mr. Richard Marsh) May I be clear on the question about Mr. Kellett which the hon. Gentleman asks? Is he asking me why no one —including the Tribunal itself—called Mr. Kellett, or merely why the Coal Board’s counsel did not call him? The Tribunal could have called anyone it wished. It did not call him.

Mr. Gibson-Watt The point of my question is that one would have expected counsel for the Coal Board to call the chairman of the division. I do not understand it. If there is a reason, I am very ready to accept what the Minister may say. I should like him to give us an answer on the point.

The Coal Board, like other nationalised industries, enjoys immunity from Parliamentary control. No Member of Parliament may ask Questions in the House about the administrative matters of nationalised industries. This gives the industries, as it were, an impregnability which I am not always sure is in their own interests. In this case, it was not possible for the hon. Member for Merthyr Tydvil to come to the House and ask the Minister concerned about the tip menace. The general public cannot understand this prohibition on Parliamentary probing. Some changes could be made. After all, Mr. Aneurin Bevan did not make that mistake with the National Health Service when he introduced it. Would it not be possible for this matter to be considered by the Select Committee on Nationalised Industries?

Many hon. Members wish to speak in the debate, and, therefore, I want only shortly to say a word about the repair work which has taken place on the Aberfan complex in draining, terracing and reseeding Tip No. 7. As far as one can judge, this has been well done, and when one goes up the valley one, sees the freshly seeded grass. The Under-Secretary of State spoke the other day of the £1 million which is to be spent by the Coal Board in reshaping the tips on Merthyr Mountain, with reseeding and planting of fair-sized trees. It remains to be seen whether this will be adequate. Fair-sized trees do not grow easily, particularly in coal tips, and the job should be done by experts.

I have no doubt that it will be, but it is not clear that Tips Nos. 4 and 5 are to be included in the landscaping. The Minister has the advantage of me, for he has seen the model and I have not. But we cannot accept any excuse that Tip No. 5 is still burning and, therefore, cannot be removed. That should be made very plain to those who are clearing up that part of Merthyr Mountain. It was stated in the Tribunal, by one of the Coal Board experts, that One may conclude that No. 5 has been standing and is standing at a very low factor of safety. Therefore, we shall need a good deal of convincing that adequate work is being done.

As the right hon. Gentleman said, there has been a good deal of Press and television coverage of the whole affair. Whatever people’s reactions to some of it may have been, it should at least remind every one of us of the debt the country as a whole owes to the mining communities and the country’s responsibility to see that the existing tips are safe, and that the lives of those living in the valleys shall not only be safer but shall be made less drab by reshaping, reseeding and re-afforestation.

It is only when one lives there or goes there that one realises that in South Wales there are not hundreds but thousands of coal tips. The real difficulty here, unlike other coal-mining areas, is that there is practically nowhere to put the tips except on the slope at the side of the valley. It is immaterial whether the slipping tip is now the property of the Coal Board or not. A number of small though potentially dangerous slips have taken place in the past few months, and throughout periods of heavy rain, such as we had recently, there is a great deal of anxiety about them.

The Secretary of State has announced that grants of between 85 and 95 per cent. will be available to local authorities under the 1966 Industrial Development Act. I do not believe that that goes quite far enough. Any local authority which is tackling a scheme of any size—say, of £250,000—and which is asked to provide 10 per cent. of the money to do the repairing and reshaping will have to find a large amount from the local ratepayers. It will probably be dealing with a coal tip that was put there some years ago and in many cases might be just a relic of a bygone economic age. Therefore, I hope that the Government will reconsider this and perhaps be even more generous to the local authorities than they have been so far.

I have no doubt that the disaster at Aberfan has taught a terrible lesson to the Coal Board, and no doubt it has made certain reorganisations. But the disaster has also brought home to us the lesson that there are many tips that need remedial action in order to relieve anxiety.

I do not wish to say anything in detail about the disaster fund. When he winds up, will the Minister tell us how the fund, totalling nearly £2 million, has been administered, and what is the up-to-date position?

I have put a number of questions to the Minister. First, will he give us the reasons why he did not accept Lord Roben’s resignation? Second, will he say why the Chairman of the South Western Division did not give evidence at the Tribunal? Third, will he consult his colleagues about changing the rules which prevent hon. Members from asking Questions about nationalised industries in the House? Fourth, will he ensure that the Coal Board adequately reshapes the tips at Aberfan? Fifth, will the Government be more generous to local authorities? Finally, will he tell us more about the disaster fund?

Having put those questions to the Minister, I conclude by saying to all who have suffered at Aberfan. “We wish you strength and faith to overcome your grief.”