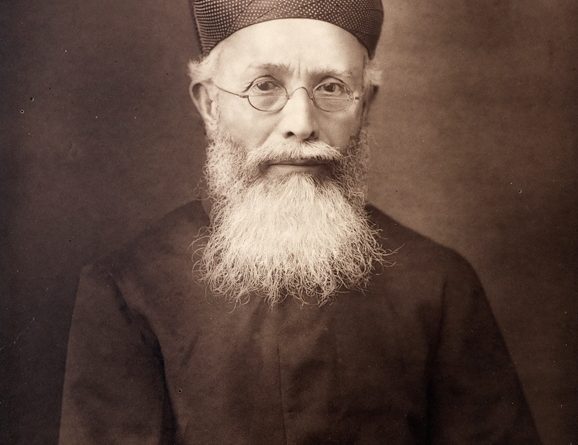

Dadabhai Naoroji – 1893 Speech on East India

Below is the text of the speech made by Dadabhai Naoroji, the then Liberal MP for Finsbury Central, in the House of Commons on 28 March 1893.

The hon. Member for Hull told us in very emphatic language of the sufferings of the Anglo-Indian Services in India. I do not blame him for that. Not only he, but even the Viceroy in his long speech went over the same ground, and in as emphatic a manner as possible portrayed what he called the sufferings, and hardships, and cruel wrongs of the Anglo-Indians, and in every way possible emphasised the demands of the Anglo-Indian servants. But it never occurred to either the hon. Member for Hull or the Viceroy that there is another side to the picture. And if these Anglo-Indians are suffering, there are also other people who are suffering far more. What is the position of the Indians themselves from the fall in this exchange? Have the hon. Member or the Viceroy, or any of the English gentlemen who are talking about this subject, given a single thought to the effect which is being produced upon the people of India? “Certainly not,” as I suppose you would say. [Cries of “No!” “Certainly!” and “Oh! oh!”]

Here is this long statement by the hon. Member for Hull, in which he has portrayed in very strong terms the sufferings of the Anglo-Indian servants, but he has not said one single word as to what the Indians them-selves have suffered. And not only the hon. Member, but the Viceroy also—as I have already said—emphasised as strongly as possible the sufferings, and used all the strong words to be found in the English vocabulary with regard to the hardships of the English servants, but in these long speeches there has not been one word of pity or sympathy with regard to those from whose pocket whatever is demanded has to be paid and what these people themselves have already suffered. Lord Macaulay has said that “the heaviest of all yokes is the yoke of the stranger.” [“Oh, oh!”] So long as this House does not understand that the yoke as it, at present exists practically in India is “the heaviest of all yokes,” India has no future, India has no hope. [Loud cries of “Oh, oh!”] You may say “Oh, oh!” but you have never been, fortunately—and I hope and pray you may never be—in the condition in which India is placed in your hands. [“Oh, oh!”] Wait a little, please. The saddest part of the picture is that while the British people and the British Parliament do not wish and have not willed that India shall be governed on the principle of “the heaviest yoke is the yoke of the stranger,” yet it is so. It is distinctly laid down what the policy is to be, and this Parliament has actually willed 60 years ago that the rule over India ought to be the rule of justice, righteousness, beneficence. That was repeated again in the great Proclamation of 1858. But what has been the actual practice? What has been done by those who have been thus instructed? The actual practice has been to make this yoke the heaviest yoke—”the yoke of the stranger.” [“Oh, oh!”] Has the hon. Gentleman who cries “Oh!” ever been in such a condition as we are? If he has not he can never understand it. I pray that you may never feel that yoke You have been free from it ever since the time when the Normans became assimilated with the English people [Cries of “Question!”] From that] time forward you have been a free people, and I hope and pray you may ever remain so. But, at the same time, it is difficult for you to even surmise the condition of the people of India.

If it is within your power to make this rule a rule of justice and honour, and at the same time beneficent and profitable, both to yourselves and to us. But I cannot now enter further into that point. The hon. Member for Hull introduced the subject of the poverty of the people of India and treated it with a light heart. That is exactly the question that has to be fought out by me upon the Floor of this House, but the time is not now. I cannot now enter into a Debate upon that point, because you, Mr. Speaker, would very properly call me to Order. I can only intimate my point, and give you some high testimony upon that subject. I will not go into my own reasons, but only quote you the testimony of some of the highest financiers of India. First of all, a Viceroy like Lord Lawrence has distinctly stated in those words—it was in the year 1864—

“India is, on the whole, a very poor country. The mass of the population enjoy only a scanty subsistence.”

Then, again, in 1873, he repeated his opinion before the Finance Committee—

“That the mass of the people were so miserably poor that they had barely the means of subsistence. It was as much as a man could do to feed his family, or half feed them, let alone spending money on what might be called luxuries or conveniences.”

Thou, coming down to a more recent date—to the days of Lord Cromer—these are the words of Lord Cromer in 1882—

“It has been calculated that the average income per head of population in India is not more than Rs.27 a year. And though I am not prepared to pledge myself to the absolute accuracy of a calculation of this sort, it is sufficiently accurate to justify the conclusion that the tax-paying community is exceedingly poor. To derive any very large increase of revenue from so poor a population as this is obviously impossible, and, if it were possible, would be unjustifiable.”

Later on this authority goes on to show the extreme poverty of the mass of the people. Then he reverts back again to the question of the Salt Tax in India—

“He would ask hon. Members to think what Rs.27 per annum was to support a person, and then he would ask whether a few annas was nothing to such poor people.”

There is the testimony of your highest Finance Minister, Lord Cromer, who is able to give a very satisfactory account of the work he is doing in Egypt, but was not able to give much encouragement as to India. And when we ask for information from the Government that would satisfactorily show whether, under the most highly praised administration in the world, and after 100 years of this administration, India is poor or not, a Finance Minister as late as 1882 expresses the same opinion as was expressed long ago. Nothing more can be said than that India is extremely poor. These are the words of your own Finance Ministers. Now take the conclusion to which Lord Cromer came in 1882, an extract from which I have read to you with regard to the income of India being not more than Rs.27 per head per annum. This calculation is based upon a Note prepared by the present Finance Minister, and I ask the Government of India, I ask the Under Secretary of State for India, for a Return here in this House of that Note. It is only by complete information given by the Government in conformity with the requirements of this House, which requires that a complete statement of the moral and material progress of India should be laid upon the Table every year, that hon. Members can become acquainted with the actual condition of India. We have it every year of a kind it is not worth the paper it is printed on. There is a certain half-truth line of view always expressed in it, but the information that is required is what is the actual income of the country from year to year. My wish, Sir is to compare figures and see whether the country is improving or becoming poorer. But such information as is needed is not given. I have asked for this Return, and what is the answer given? “That it is out of date.” That is to say, that while this Note of 1881 was the basis upon which this public statement was made by Lord Cromer, this Return is not to be given to us.

I now ask again that this Return should be given to us, and also a similar Return for 1891, that we may compare and judge whether India is really making any progress or not. Until you get this complete information before the House year by year, you will not be able to form a correct judgment as to the improvement of India. So far, we have, however, these high financial authorities telling us that India is the poorest country in the world, that it is even poorer than Russia. I trust that these facts are sufficient to satisfy hon. Gentlemen. Again, never has England spent, so far as I know, and so far as my information goes, never has there been a single farthing spent out of the British Exchequer, either for the acquirement of India, or for the maintenance of it, or administration, or in any manner connected with India, whilst at the same time hundreds of millions of the wealth of India have been constantly poured into this country. Whether any country in the world could stand such drain as India is subjected to is utterly out of the question. If England itself, with all its wealth, was subjected to such a drain as India is subjected to, it would be reduced to extreme poverty before long.

When the necessary information is before this House I shall be able to show how during the whole of this century Englishmen themselves have pointed out that India was kept impoverished. Now, what has been the effect upon the natives of India—the taxpayers themselves—from the fall in exchange? During the 20 years from 1873 up to the present day there has been a heavy loss in exchange in the remittances for home charges. I am not hero to-night discussing the justice or injustice of the home charges; I am taking the home charges as they stand, and taking the effect upon the Indian taxpayers. The people live on a very scanty subsistence, and, according to your highest financial authorities, they are extremely poor, yet in their ordinary condition they have to pay Rs. 100,000,000 to the Anglo-Indian servants for salaries, &c., of Rs. 1,000 and upwards per annum, and salaries under Rs. 1,000 besides. There is a large military expenditure to be kept up, and you have other payments under “the system of the yoke of the stranger.” All this means a great loss of wealth, wisdom, work, and capacity to India. I hope the House will be able to take all these points into consideration. Now let us see what a further heavy burden is put upon India by this fall in the exchange!

There has been already, during the last 20 years, about Rs. 650,000,000 lost to the taxpayer on account of this fall of the exchange, and before next year is over it will be something like Rs. 1,000,000,000. And with these heavy burdens under which the taxpayer of India are groaning, you do not pay the slightest attention to them. You simply think of the sufferings and hardships of your own fellow-countrymen, for which I do not blame you at all. [“Oh, oh!”] It is only natural you should feel for them, but at the same time you ought to have some heart and some justice to consider from what sources this money has to be made up. You do not give a single thought to the sufferings of the men who are being ground to the very dust—as Sir Grant Duff once truly said. To these people who are being literally ground and crushed to dust and powder you wish to add a still heavier burden. They have already suffered greatly from these causes. Can you have the heart to do it? They are a poor people living on a scanty subsistence, merely hewers of wood and drawers of water. I can say nothing more. I leave the matter to your sense of justice, to your heart, to consider whether it is right or proper that you should put still more burdens upon these poor people already so low.

I have said there has not been a single shilling spent, out of the British Exchequer upon India during all this long connection. But I should make this one exception. On the occasion of the last Afghan War the then Prime Minister, who is also now, offered and gave £5,000,000 towards the expenses that were put upon us by the War. But that was only about one-fourth of the expenses of that iniquitous war. We suffered very heavily by that Afghan War, and heavy military expenses are going on without check or hindrance. Had the British people to pay (which they must pay at least in some fair proportion), we would have heard on this very floor a great deal about them. Now the House is asked by the hon. Member for Hull to put another burden upon the Indian taxpayer. What is the use of asking this?

The fact is the Viceroy has already committed himself in as strong language as he could that he would do something for the Anglo-Indians, whether the burden upon the poor taxpayers becomes greater or not. He has not said a word about the sufferings of the poor Indian taxpayer. He has not even thought of him. The only thing he said in his long speech was that he did not yet add to the taxation simply because he thought it would be a temporary difficulty. But if it became a permanent difficulty, and as the Anglo-Indian Services could not tolerate the suffering that they have been put to, then he would determine to do something for them by additional taxation. “Very well, then,” says the hon. Member for Hull, “we must do something.” You should not put the expense on the poor native taxpayer, who has no vote. One right hon. Member talked about the vote, and that is just because the poor Indian has no vote that there is so little heed for him. He is truly helpless and crushed down with every possible burden. If hon. Gentlemen here, after drawing millions from the native taxpayer, intend to put this additional burden upon him, then I can only say Heaven save him.

With regard to the proposed relief, I would like to direct the attention of hon. Gentlemen to the words of the Viceroy in which he almost wholly commits himself to do something. In the face of that admission what is the good of a Committee. The Viceroy says that, whatever may be the Report of Lord Herschell’s Committee, he is determined that if the present state of things continues, the distress which has been borne for some time past by the officials cannot continue to be tolerated. Well, after that you may appoint Committees, but what the result will be is perfectly clear. You have a Committee of Europeans, you have European witnesses, European interests, and all the European sympathy. We know very well what the result will be of the deliberations of such a Committee. We have had ample experience of those Committees in the past. At all gatherings which had been held, where the interests of Europeans and Indians clashed, we know very well that the Indians had gone to the wall. There has hardly been an instance in which a Commission has sat on such a matter as this, and decided in a manner that can be called impartial and unbiassed. [Cries of “Agreed, agreed!”] I can quite understand that hon. Gentlemen should become impatient.

A Committee is not required to prove the cases the hon. Member for Hull has brought forward. No doubt there is a great deal of suffering, but I ask you not to drag the relief from those who are already crushed, or as he himself said, not to be liberal with other wretched people’s money. I appeal to the British people in this instance to say that it is proper, right, and just that the British Exchequer should find the amount of money wanted. I will give a special reason for this. Every farthing that will be paid for this relief will be spent in this country. It will be simply passing from one hand to another. On the other hand, if you put the burden on the Indians, it means that every farthing taken out of their scanty substance will be carried away from India to this country, and thus our distress and our poverty will be enhanced. The money given for this relief will not be spent in India, but in this country, and I appeal to your justice, to your honour, and to your conscience whether it would be right to put such additional burden on the taxpayer of India? At the present exchange he has lost nearly Rs. 1,000,000,000. I appeal to hon. Gentlemen of this House, to the British people at large, that in this case especially it will be the right and proper and humane thing to give this relief to Anglo-Indian servants from the British Exchequer.

The Motion is for a Committee. You may have it, but it is merely a farce; the whole thing is a foregone conclusion. Do not put additional taxation on these poor people. The pressure at present upon them is already far too heavy. Lastly, the only effective and permanent remedy for our woes is to remove the cause—the inordinately heavy foreign agency must be reduced to reasonable dimensions—and then there will be no burden and no problem of loss by exchange. Remove the yoke of the stranger and make it the rule of the benefactor, and you will be as much blessed and benefited as we.