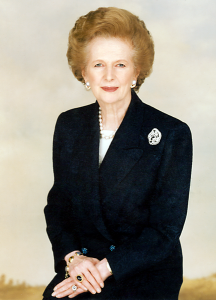

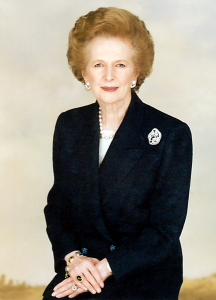

The speech made by Margaret Thatcher, the then Prime Minister, to the Conservative Party Conference in Bournemouth on 10 October 1986.

Mr President, this week at Bournemouth, We’ve had a most responsible Conference:

The Conference of a Party which was the last Government, is the present Government, and will be the next Government. We have heard from ministers a series of forward-looking policies which are shaping the future of our country.

And not only from ministers, but from the body of the hall has come speech after speech of advice, encouragement and commitment.

We are a Party which knows what it stands for and what it seeks to achieve.

We are a Party which honours the past that we may build for the future.

Last week, at Blackpool, the Labour Party made the bogus claim that it was “putting people first”.

Putting people first?

Last week, Labour

— voted to remove the right to a secret ballot before a strike

— voted to remove the precious right we gave to trade union members to take their union to a Court of Law.

Putting people first?

Last week Labour voted for the State to renationalise British Telecom and British Gas, regardless of the millions of people who have been able to own shares for the first time in their lives.

Putting people first?

They voted to stop the existing right to buy council houses, a policy which would kill the hopes and dreams of so many families.

Labour may say they put people first; but their Conference voted to put Government first and that means putting people last.

What the Labour Party of today wants is:

— housing—municipalised

— industry—nationalised

— the police service—politicised

— the judiciary—radicalised

— union membership—tyrannised

— and above all—and most serious of all—our defences neutralised.

Never!

Not in Britain.

We have two other Oppositions who have recently held their Conferences, the Liberals and the SDP.

Where they’re not divided they’re vague, and where they’re not vague they’re divided. At the moment they appear to be engaged in a confused squabble about whether or not Polaris should be abandoned or replaced or renewed or re-examined.

And if so, when; and how; and possibly why?

If they can’t agree on the defence of our country, they can’t agree on anything.

Where Labour has its Militant tendency, they have their muddled tendency.

I’ll have rather more to say about defence later.

CONSERVATIVE MORALITY

But just now I want to speak about Conservative policies, policies which spring from deeply held beliefs.

The charge is sometimes made that our policies are only concerned with money and efficiency.

I am the first to acknowledge that morality is not and never has been the monopoly of any one Party.

Nor do we claim that it is.

But we do claim that it is the foundation of our policies.

Why are we Conservatives so opposed to inflation?

Only because it puts up prices?

No, because it destroys the value of people’s savings.

Because it destroys jobs, and with it people’s hopes.

That’s what the fight against inflation is all about.

Why have we limited the power of trade unions?

Only to improve productivity?

No, because trade union members, want to be

Protected from intimidation and to go about their daily lives in peace—like everyone else in the land.

Why have we allowed people to buy shares in nationalised industries?

Only to improve efficiency?

No.

To spread the nation’s wealth among as many people as possible.

Why are we setting up new kinds of schools in our towns and cities?

To create privilege?

No.

To give families in some of our inner cities greater choice in the education of their children.

A choice denied them by their Labour Councils.

Enlarging choice is rooted in our Conservative tradition.

Without choice, talk of morality is an idle and an empty thing.

BRITAIN’S INDUSTRIAL FUTURE

Mr. President, the theme of our conference this week is the next move forward.

We have achieved a lot in seven short years. But there is still a great deal to be done for our country.

The whole industrial world, not just Britain, is seeing change at a speed that our forebears never contemplated, much of it due to new technology.

Old industries are declining.

New ones are taking their place.

Traditional jobs are being taken over by computers. People are choosing to spend their money in new ways.

Leisure, pleasure, sport and travel.

All these are big business today.

It would be foolish to pretend that this transition can be accomplished without problems.

But it would be equally foolish to pretend that a country like Britain, which is so heavily dependent on trade with others, can somehow ignore what is happening in the rest of the world.

— can behave as if these great events have nothing to do with us.

— can resist change.

Yet that is exactly what Labour proposes to do:

They want to put back the clock and set back the country.

Back to State direction and control.

Back to the old levels of overmanning.

Back to the old inefficiency.

Back to making life difficult for the very people on whom the future of Britain depends—the wealth creators, the scientists, the engineers, the designers, the managers, the inventors—all those on whom we rely to create the industries and jobs of the future.

What supreme folly.

It defies all common sense.

JOBS

As do those Labour policies which, far from putting people first, would put them out of jobs.

The prospects of young people would be blighted by Labour’s minimum wage policy, because people could not then afford to employ them and give them a start in life.

A quarter of a million jobs could be at risk.

Many thousands of jobs would go from closing down American nuclear bases.

Labour want sanctions against South Africa.

Tens of thousands of people could lose their jobs in Britain—quite apart from the devastating consequences for black South Africans.

Out would go jobs at existing nuclear power stations.

Whatever happened to Harold Wilson’s ‘white heat of technological revolution’?

On top of all this, jobs would also suffer as would-be investors in Britain took one look at Labour and decided to set up elsewhere.

Labour say they would create jobs.

But those policies would destroy jobs.

This Government has created the climate that’s produced a million extra jobs over the Past three years.

Here in Britain, it is encouraging that more of the population are in work than in Italy, or France, or Germany.

Nevertheless, as you heard yesterday, more has to be done, and is being done.

Meanwhile, no other country in Europe can rival our present range of help for people to train, retrain and find jobs.

And I would like just to say, Mr President: training is not a palliative for unemployment.

Training will play an ever larger part in our whole industrial life.

For only modern, Efficient industry and commerce will produce the jobs our people need.

POPULAR CAPITALISM

Our opponents would have us believe that all problems can be solved by State intervention. But Governments should not run business.

Indeed, the weakness of the case for State ownership has become all too apparent.

For state planners do not have to suffer the consequences of their mistakes. It’s the taxpayers who have to pick up the bill.

This Government has rolled back the frontiers of the State, and will roll them back still further.

So popular is our policy that it’s being taken up all over the world.

From France to the Phillipines, from Jamaica to Japan, from Malaysia to Mexico, from Sri Lanka to Singapore, privatisation is on the move, there’s even a special oriental version in China.

The policies we have pioneered are catching on in country after country.

We Conservatives believe in popular capitalism—believe in a property-owning democracy.

And it works!

POWER TO THE PEOPLE

In Scotland recently, I was present at the sale of the millionth council house: to a lovely family with two children, who can at last call their home their own.

Now let’s go for the second million!

And what’s more, millions have already become shareholders.

And soon there will be opportunities for millions more, in British Gas, British Airways, British Airports and Rolls-Royce.

Who says we’ve run out of steam.

We’re in our prime!

The great political reform of the last century was to enable more and more people to have a vote.

Now the great Tory reform of this century is to enable more and more people to own property.

Popular capitalism is nothing less than a crusade to enfranchise the many in the economic life of the nation.

We Conservatives are returning power to the people.

That is the way to one nation, one people.

RETURN OF NATIONAL PRIDE

Mr President, you may have noticed there are many people who just can’t bear good news.

It’s a sort of infection of the spirit and there’s a lot of it about.

In the eyes of these hand-wringing merchants of gloom and despondency, everything that Britain does is wrong.

Any setback, however small, any little difficulty, however local, is seen as incontrovertible proof that the situation is hopeless.

Their favourite word is “crisis”.

It’s crisis when the price of oil goes up and a crisis when the price of oil goes up and a crisis when the price of oil comes down.

It’s a crisis if you don’t build new roads,

It’s a crisis when you do.

It’s a crisis if Nissan does not come here,

And it’s a crisis when it does.

It’s being so cheerful as keeps ’em going.

What a rotten time these people must have, running round running everything down.

Especially when there’s so much to be proud of.

Inflation at its lowest level for twenty years.

The basic rate of tax at its lowest level for forty years.

The number of strikes at their lowest level for fifty years.

The great advances in Science and industry.

The achievement of millions of our people in creating new enterprises and new jobs.

The outstanding performance of the arts and music and entertainment worlds.

And the triumphs of our sportsmen and women.

They all do Britain proud.

And we are mighty proud of them.

CONSERVATIVES CARE

Our opponents, having lost the political argument, try another tack!

They try to convey the impression that we don’t care.

So let’s take a close look at those who make this charge.

They’re the ones who supported and maintained Mr Scargill ‘s coal strike for a whole year, hoping to deprive industry, homes and pensioners of power, heat and light.

They’re the ones who supported the strike in the Health Service which lengthened the waiting time for operations just when we were getting it down.

They’re the ones who supported the teachers’ dispute which disrupted our children’s education.

They are those Labour Councillors who constantly accuse the Police of provocation when they deal with violent crime and drugs in the worst areas of our inner cities.

Mr President, we’re not going to take any lessons in caring from people with that sort of record.

We care profoundly about the right of people to be protected against crime, hooliganism and the evil of drugs.

The mugger, the rapist, the drug trafficker, the terrorist—all must suffer the full rigour of the law.

And that’s why this Party and this Government consistently back the Police and the Courts of Law, in Britain and Northern Ireland.

For without the rule of law, there can be no liberty.

It’s because we care deeply about the Health Service, that we’ve launched the biggest hospital building programme in this country’s history.

Statistics tell only part of the story.

But this Government is devoting more resources of all kinds to the Health Service than any previous Government.

Over the past year or so, I’ve visited five hospitals.

In the North west, at Barrow in Furness—I visited the first new hospital in that district since the creation of the Health Service forty years ago.

In the North East—another splendid new hospital, at North Tyneside, with the most wonderful maternity unit and children’s wards.

Just North of London I went round St Albans’ Hospital where new wards have been opened and new buildings are under way.

I visited the famous Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital for women, which this Government saved.

The service it provides is very special and greatly appreciated.

And then last week I went back to the Royal Sussex County Hospital in Brighton, to open the new renal unit.

Many of us have cause to be very thankful for that Brighton hospital.

Everywhere patients were loud in their praise of the treatment they received from doctors and nurses whose devotion and skill we all admire.

This Government’s record on the Health Service is a fine one.

We’re proud of it and we must see to it that people know how much we’ve done.

Of course there are problems still to be solved.

The fact that there’s no waiting list in one area does not help you if you have to wait for an operation in your area.

It doesn’t help if there’s a new hospital going up somewhere else, but not where you’d really like it.

We are tackling these problems.

And we shall go on doing so, because our commitment to the National Health Service is second to none.

We’ve made great progress already.

The debate we had on Wednesday, with its telling contributions from nurses and doctors in the Health Service, was enormously helpful to us.

It’s our purpose to work together and to continue steadily to improve the services that are provided in hospital and community alike.

This is conservatives putting care into action.

And we care deeply that retired people should never again see their hard-earned savings decimated by runaway inflation.

For example, take the pensioner who retired in 1963 with a thousand pounds of savings.

Twenty years later, in 1983, it was only worth one hundred and sixty pounds.

That is why we will never relent in the battle against inflation.

It has to be fought and won every year.

We care passionately about the education of our children.

Time and again we hear three basic messages:

— bring back the three Rs into our schools;

— bring back relevance into the curriculum;

— and bring back discipline into our classrooms.

The fact is that education at all levels—teachers, training colleges, administrators—has been infiltrated by a permissive philosophy of self-expression.

And we are now reaping the consequences which, for some children, have been disastrous.

Money by itself will not solve this problem.

Money will not raise standards.

But:

— by giving parents greater freedom to choose;

— by allowing head teachers greater control in their school;

— by laying down national standards of syllabus and attainment;

I am confident that we can really improve the quality of education.

Improve it not just in the twenty new schools but in every school in the land.

And we’ll back every teacher, head teacher and administrator who shares these ideals.

DEFENCE

Mr President, we care most of all about our country’s security. The defence of the realm transcends all other issues.

It is the foremost responsibility of any Government and any Prime Minister.

For forty years, every Government of this country of every political persuasion has understood the need for strong defences.

— By maintaining and modernising Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent.

— By membership of the NATO Alliance, an alliance based on nuclear deterrence.

— And by accepting, and bearing in full, the obligations which membership brings.

All this was common ground.

Last week, Mr President, the Labour Party abandoned that ground.

In a decision of the utmost gravity, Labour voted to give up Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent unilaterally.

Labour would also require the United States to remove its nuclear weapons from our soil and to close down its nuclear bases:

weapons and bases which are vital, not only for Britain’s defence, but for the defence of the entire Atlantic Alliance.

Furthermore, Labour would remove Britain altogether from the protection of America’s nuclear umbrella, leaving us totally unable to deter a nuclear attack.

For you cannot deter, with conventional weapons, an enemy which has, and could threaten to use, nuclear weapons.

Exposed to the threat of nuclear blackmail, there would be no option but surrender.

Labour’s defence policy—though “defence” is scarcely the word—is an absolute break with the defence policy of every British Government since the second world war.

Let there be no doubt about the gravity of that decision.

You cannot be a loyal member of NATO while disavowing its fundamental strategy.

A Labour Britain would be a neutralist Britain.

It would be the greatest gain for the Soviet Union in forty years.

And they would have got it without firing a shot.

I believe this total reversal of Labour’s policy for the defence of our country will have come as a shock to many of Labour’s traditional supporters.

It was Labour’s Nye Bevan who warned his party against going naked into the Conference chamber.

It was Labour’s Hugh Gaitskell who promised the country to fight, fight and fight again against the unilateral disarmers in his own party.

That fight was continued by his successors.

Today the fight is over.

The present leadership are the unilateral disarmers.

The Labour Party of Attlee, of Gaitskell, of Wilson is dead.

And no-one has more surely killed it than the present leader of the Labour Party,

There are some policies which can be reversed.

But weapon development and production takes years and years.

Moreover, by repudiating NATO’s nuclear strategy Labour would fatally weaken the Atlantic Alliance and the United States’ commitment to Europe’s defence.

The damage caused by Labour’s policies would be irrevocable.

Not only present but future generations would be at risk.

Of course there are fears about the terrible destructive power of nuclear weapons.

But it is the balance of nuclear forces which has preserved peace for forty years in a Europe which twice in the previous thirty years tore itself to pieces.

Preserved peace not only from nuclear war, but from conventional war in Europe as well.

And it has saved the young people of two generations from being called up to fight as their parents and grandparents were.

As Prime Minister, I could not remove that protection from the lives of present and future generations.

Let every nation know that Conservative Governments, now and in the future, will keep Britain’s obligations to its allies.

The freedom of all its citizens and the good name of our country depend upon it.

This weekend, President Reagan and Mr Gorbachev are meeting in Reykjavik.

Does anyone imagine that Mr Gorbachev would be prepared to talk at all if the West had already disarmed?

It is the strength and unity of the West which has brought the Russians to the negotiating table.

The policy of her Majesty’s Opposition is a policy that would help our enemies and harm our friends.

It totally misjudges the character of the British people.

After the Liberal Party Conference, after the SDP Conference, after the Labour Party Conference, there is now only one party in this country with an effective policy for the defence of the realm.

That party is the Conservative Party.

OUR VISION

Mr. President, throughout this conference we have heard of the great achievements of the last seven years.

Their very success now makes possible the next moves forward, which have been set out this week.

And we shall complete the manifesto for the next election—within the next eighteen months

That Manifesto will be a programme for further bold and radical steps in keeping with our most deeply held beliefs.

We do our best for our country when we are true to our convictions.

As we look forward to the next century, we have a vision of the society we wish to see. The vision we all serve.

We want to see a Britain where there is an ever-widening spread of ownership, with the independence and dignity it brings.

— A Britain which takes care of the weak in their time of need.

We want to see a Britain where the spirit of enterprise is strong enough to conquer unemployment North and South.

— A Britain in which the attitude of “them and us” has disappeared from our lives.

We want to see a Britain whose schools are a source of pride and where education brings out the best in every child.

— A Britain where excellence and effort are valued and honoured.

We want to see a Britain where our streets are free from fear, day and night.

And above all, we want to see a Britain which is respected and trusted in the world, which values the great benefits of living in a free society, and is determined to defend them.

Mr. President, our duty is to safeguard our country’s interests, and to be reliable friends and allies. The failure of the other parties to measure up to what is needed places an awesome responsibility upon us.

I believe that we have an historic duty to discharge that responsibility and to carry into the future all that is best and unique in Britain.

I believe that our Party is uniquely equipped to do it.

I believe the interests of Britain can now only be served by a third Conservative victory.