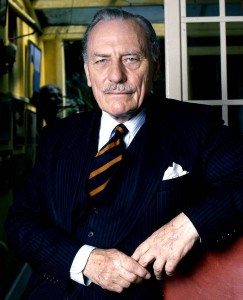

Below is the text of the maiden speech made by Richard Attenborough in the House of Lords on 22 November 1994. The speech was in reply to the Loyal Address and was the only contribution Lord Attenborough made in the Lords.

My Lords, it would perhaps have been more appropriate had I been able to deliver these few words during the arts debate last January when my noble friend Lord Menuhin made his impressive maiden speech but, sadly, a bout of ‘flu confined me to my bed. I also wish to apologise to my most kindly sponsors—friends of long standing; the noble Lords, Lord Cledwyn and Lord Walton—for the subsequent delay in making my own maiden speech; a delay occasioned by a lengthy professional commitment in the United States and a tour of South Africa on behalf of the United Nations Children’s Fund.

Nevertheless, as possibly noble Lords may have surmised, my subject is the arts—the arts in their broadest sense; the arts as an essential element in what we are pleased to call our civilised society. I have it on the best of authority, from a not too distant relative, that we are related to apes, but it is, surely, not only the ability to stand on our hind legs that sets us so singularly apart from the animal kingdom. The crucial difference must lie in what we call soul and creativity. Our distant ancestors, the first true humans, started to communicate through language some 35,000 years ago and, almost contemporaneously, they began to create pictures on the walls of their caves.

Is it not remarkable that those early hunters, balanced as they were on the very cusp of survival, should need to paint the creatures which surrounded them in their daily lives: that in the bowels of the earth and on bare rock they felt impelled to recreate the colour, form and movement that they witnessed in the forest outside? A cave painting tells us, surely, far more than the simple appearance of a bison or deer. Across untold generations it speaks of the painter, too; of his uniquely personal interpretation. It grants us a window into his mind. President John F. Kennedy once said: Art establishes the basic human truths which must serve as the touchstone of our judgement”. From the very earliest of times the arts have been an instinctive essential of our humanity. They are a miraculous sleight of hand which reveal the truth and a glorious passport to greater understanding between the peoples of the world. The arts not only enrich our lives but grant us the opportunity to challenge accepted practices and assumptions. They give us a means of protest against that which we believe to be unjust; a voice to condemn the brute and the bully; a brief to advocate the cause of human dignity and self-respect; a rich and varied language through which we can express our national identity.

Today, as a nation, we face daunting problems—problems which are obliging us to examine the very fabric of our society. And the role of the arts in healing a nation divided, a nation in which too many lack work, lack self esteem, lack belief and direction, cannot and must not be underestimated.

This is the first century of mass communication. We have now, as never before, the ability to disseminate the arts in all their forms, cheaply, quickly and qualitatively, to the widest possible audience. But art—any art form—can never rest upon its laurels. It was Winston Churchill who said: Without tradition, art is a flock of sheep without a shepherd. Without innovation, it is a corpse”. The arts in this country have a long and enviable tradition. Shepherds there are in abundance. But innovation which must, of necessity, entail the possibility of ridicule, even failure, is the life blood of continuing tradition. For the arts to continue to flourish we must underwrite both innovation and, of course, training.

We have in the United Kingdom some of the finest academies of dance and drama in the entire world. Is it not, then, a supremely tragic irony that many of our most promising students are being denied access to those institutions for lack of a mandatory grant? As a result, hundreds of dedicated and talented young people are now being lost to their chosen professions as dancers, actors and technicians, with their places taken by those who can afford to pay. The loss of their talents, furthermore, is inflicting untold damage on our internationally acclaimed theatre, television and film industries.

Film, the movies, as noble Lords may be aware, has occupied much of my life. It is now more than 50 years since I entered the industry. In that time I have seen it weather many storms and falter repeatedly from lack of concern on the part of far, far too many arts Ministers. Certainly, now that at last every aspect of our cinema industry is under the sole aegis of the Department of National Heritage, such pitiful inactivity can no longer be excused.

Sadly, however, from my own particular viewpoint, cinema was scarcely mentioned during the arts debate to which I referred earlier—a fact I register with regret since I believe the vast majority of the British people generally accept that it is the art form of this century. My belief is borne out by recent figures which indicate that United Kingdom cinema attendances for 1994 will reach 120 million; the 10th successive year of steady increase from a base of less than half that figure. In fact, three times more people go to the movies than all those who attend concerts, opera, ballet and theatre put together and we currently spend, as a nation, nearly £2 billion a year on watching feature films, either at home or in the cinema. However, the sad fact is that only some 4 per cent. of that revenue will accrue to films of British origin.

We, as indigenous film makers, are often accused of special pleading, of extending the perpetual begging bowl. That is not true. The fact is that the making of feature films cannot be compared with any other manufacturing process. Every film made is a prototoype, a one-off original, that must be packaged and marketed in its own distinctive fashion —a procedure that is extremely risky and very expensive.

Since no one film can ever be guaranteed to make a profit, wise investors will spread their risk over 10 or 20 such prototypes in the knowledge that 50 per cent. will fail, 30 per cent. will break even and 20 per cent. will prove immensely profitable. If we in Britain are ever again to have a film industry worthy of the name, we have to persuade government to create conditions that will allow investors to spread their risk in that way.

Some, of course, might argue that our film industry is not worth saving, that it should be allowed to go the way of shipbuilding or the manufacture of motor cycles. But I repeat that the making of feature films cannot be compared with any other industrial process, for they represent, as no other art form, as no other business activity, a crucial definition of our cultural identity, both here at home and throughout the world. Movies are the mirror we hold up to ourselves, the reflection of our codes and practices, our goods and services, our skills and inventions, our architecture and landscapes, our comedy and tragedy, our past and present. And they have the ability to grant us, as no other medium can, a worldwide showcase, generating immense returns—both tangible and intangible, visible and invisible—in every conceivable sphere.

The novelist Julian Barnes wrote a decade ago: Do not imagine that Art is something which is designed to give gentle uplift and self-confidence. Art is not a brassière. At least, not in the English sense. But do not forget that brassière is the French for life-jacket”. Today we have need of that life-jacket as never before. The arts are not a luxury. They are as crucial to our well-being, to our very existence, as eating and breathing.

A recent survey, undertaken for the National Campaign for The Arts, revealed that 79 per cent. of the population attend arts or cultural events, that the same high percentage believe that the arts help to bring people together in local communities and almost the same number are prepared to state, without equivocation, that the arts enrich their quality of life. In the face of such cogent endorsement, the role of the arts in all our lives—in health care, in social education and rehabilitation, in business, in the community—is, I profoundly believe, one that we underestimate at our peril.

Some years ago, when I had the privilege of helping to prepare a report concerning the arts and disabled people, I was reminded of Somerset Maugham, who wrote: An art is only great and significant if it is one that all may enjoy”. “Exclusive” is a shameful word in the context of the arts. We have, as a nation, excluded far too many for far too long. Whether consciously or unconsciously, we have assumed that certain of our compatriots, most notably the disabled and the disadvantaged, have little to gain and little to contribute. Nothing could be further from the truth. In common, I am certain, with many Members of this noble House, I am encouraged by mention in the gracious Speech of the Government’s intention to introduce a new Bill to ameliorate the many inequities which confront the disabled. Mindful of the constraints placed upon those making their maiden speech, I will content myself with adding that I trust their present intention will ultimately result in a more productive and seemly outcome than that which befell the Private Member’s Bill earlier this year.

The arts are not a perquisite of the privileged few; nor are they the playground of the intelligentsia. The arts are for everyone—and failure to include everyone diminishes us all.