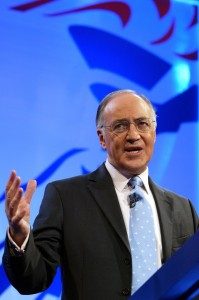

Below is the text of the speech made by David Mellor, the then Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department, in the House of Commons on 17 February 1986.

I welcome the interest which the hon. Member for Berwick-upon-Tweed (Mr. Beith) has consistently shown in these two establishments and his acknowledgement tonight of their constructive relationship with the local community, which I also welcome. I am glad to have this opportunity to respond to the matters which he raised, and I shall try to deal with as many of them as I can in the time available. In the event that I fail to deal with all of them, I shall write to the hon. Gentleman about any outstanding matters.

May I begin with Castington youth custody centre. Castington’s security and control record is good. There has not been an escape from the youth custody centre since April 1983. That occasion, when three inmates escaped and were recaptured, has been the only escape since it was opened in January 1983.

However, there have been several incidents. Last year, there were two short lived and passive demonstrations. In the first, 37 trainees refused to leave the association area at lock-up and remained there for about an hour. On the second occasion, 18 trainees made a similar gesture, although that one lasted for only a few minutes.

In addition, during 1985, there were 20 incidents involving 45 inmates in which cells were barricaded or damaged. A further relatively minor case occurred on Friday. Most of them were confined to barricading the doors and damaging cell equipment, but on the night of 28 June 1985, three trainees broke through the walls of their cells and climbed on to the roof of their wing.

During 1985 there were three further occasions when inmates broke through the walls of their cells in that way. I am glad to say that there have been no more since the new year. I join the hon. Gentleman in paying tribute to the courage and professionalism shown by staff in dealing with those incidents.

The strengthening of cells would seem to be called for in the light of what has happened. As the hon. Gentleman will be aware, the national chairman of the Prison Officers Association wrote to the Department in October, expressing his members’ anxiety about the position. The Department’s reply last month explained that the cell walls had been constructed of low density concrete blocks which were of the usual current standard for youth custody centres such as Castington. There have not been comparable problems on the same scale at other centres, and I do not believe that we would be justified in applying a general increase in standards because of problems at Castington. Moreover, because of the population pressures generally within the prison system we cannot contemplate the wholesale temporary removal of prisoners at Castington to carry out regrading work to the cells.

We are, and would have to be on the facts, worried about the position at Castington. We have strengthened the walls of eight cells by the application of robust steel mesh covered with concrete. We are considering the possibility of similarly upgrading a few additional cells in each wing to provide the governor with a flexible amount of accommodation in which to put troublesome trainees. I hope that that is a step in the right direction.

We are also about to embark on a programme of welding together the constituent parts of the beds in each cell and anchoring them to the floor.

In the two wings to be opened later this year, cells have been provided with doors that can open outwards to prevent barricading. That will deny inmates the lime in which to cause serious damage, let alone penetrate the cell wall. I hope that the work will go a long way towards eliminating the problems that the governor and his staff have experienced.

The current control position is that, following each incident, the appropriate disciplinary action was taken. The position is being monitored by the regional director. As the hon. Gentleman knows, the governor and the staff have devoted considerable effort to the creation of a positive relationship with the inmates. Recent months have seen reductions in offences against discipline and a more relaxed atmosphere.

Castington already keeps all its inmates fully and constructively occupied. It is in the final stages of a redevelopment scheme which, as well as increasing its population from 180 to 300, will further expand the facilities and enable additional playing fields, as well as a planned hard surface area, to be brought into use. It is expected that some of those facilities will be brought into use by the end of the year.

I shall say a brief word about the national staffing scene in response to what the hon. Gentleman said about it. He expressed anxiety about the effect on the establishment of the limited funds available for prison officer overtime. To put that in context, prison officer numbers, nationally, are higher than they have ever been. They stood at 18,600 on 1 January this year. That represents and increase of about 18 per cent. since 1979. Over the same period the inmate population increased by about 12 per cent.

During the next three years—from April this year to March 1989—we plan to recruit a further 3,500 staff. Although most of those will be required to man new accommodation, some are intended to relieve pressure at existing establishments where that is justified. Despite that injection of staff, however, there remains a difference between the number of staff employed and the authorised staffing levels.

In the northern region, the shortfall between staff in post and authorised staffing levels is currently running at about 17·5 per cent. Acklington reflects that regional average. Castington, however, is staffed to within 9 per cent. of its authorised level. That favourable treatment of Castington reflects its proposed role in the handling and containment of a long-term and life sentence population.

The nationally high level of overtime working in the prison service—on average about 16 hours a week—must be seen as a major problem. We have set a cash limit on the overtime budget this year, but I must emphasise that we have not cut expenditure in cash terms. The budget, at £81·6 million, is some £5 million more than last year’s spend, and a further cash increase is proposed for next year’s budget.

The overtime budget has not significantly affected the regime at either Acklington or Castington. There has been somewhat less scope for local staff training than one might have wished, but nearly half of Castington’s discipline staff and three quarters of those at Acklington have so far undergone the four-day course in control and restraint training.

The hon. Gentleman mentioned the introduction of lifers, which is of special interest to me as I carry responsibility in the Home Office for case work on life sentence prisoners, and he expressed anxiety about their introduction at Castington. There are three main centres for young offenders who are serving sentences of custody for life, detention during Her Majesty’s pleasure and detention for life. They are located at the youth custody centres at Aylesbury, Exeter and Swinfen hall, near Lichfield. It is recognised that there is a need for a young offender lifer centre in the north and we believe that Castington will be the right establishment to take on the role.

I must make it clear, however, that there are, as yet, no firm plans to transfer young offender lifers into Castington. Such a development would be preceded by very careful preparation of staff for work with this special group of young offenders. We shall not proceed until we are satisfied that Castington can properly and safely be asked to assume this function. The hon. Member may take it that we shall keep in touch with him on that so that his representations can be given their proper weight. I appreciate his sensitivity to the concerns of those who work in the prison and of his constituents who live in the surrounding area.

Acklington is a category C establishment, which means that it caters for prisoners who cannot be trusted in wholly open conditions but are not considered to pose a serious danger to the public. The level of security of prisons such as Acklington is commensurate with that judgment. In that context, the prison’s security record has been pretty good. In 1983, four prisoners escaped but were recaptured almost immediately. In 1984 there were no escapes from within the prison, although one prisoner absconded from an outside working party. In 1985, five prisoners escaped. Two were recaptured within 48 hours and the others have since been returned to custody.

It has been suggested that some arrangement for alerting the local community of an escape should be instituted. This matter has, of course, been carefully considered by the prison authorities in consultation with the police. The arrangements that are made have to find a balance between the need to alert the public to be on the look out with the need to avoid causing undue anxiety. The view that has been taken is that the local radio station provides the best medium of communication for this purpose. I am grateful for the hon. Gentleman’s assent to that. If he has any suggestions, we will be happy to consider them.

I can confirm that there are indeed plans to demolish a substantial number of the derelict houses on the perimeter after the failure of attempts to offer them to the local authority. It is sad that that did not work out, but there we are.

The hon. Member mentioned mess staffing. It is true that the prison department has recently proposed that, unless there are very strong reasons to the contrary, officers’ messes should be staffed by civilian cooks. This is more economic, but that is not the only reason for making the change. It is in principle inappropriate to use a highly trained prison officer or prison auxiliary on this work. It is, indeed, highly desirable to release such officers for other duties more appropriate to their grade. It is much the same argument as that which has led to the replacement of police officers by ancillary office workers.

We are pursuing a consistent policy in the law and order services. Prison officers are badly needed elsewhere. The figures that I gave earlier demonstrate that. We expect to avoid redundancies and are of course prepared to retain prison auxiliaries on mess duties when no other posts can be found for them.

The hon. Gentleman referred to his concern that inmates might in future be employed in the mess under the supervision of a civilian rather than a prison officer. We shall consider carefully the views of local management and staff on this point, but in general I do not share the Prison Officers Association’s concern about this policy. Any inmates working in the mess will have been specially selected for that purpose. Civilians supervise inmates in messes and elsewhere at other establishments without difficulty. I stress that no decision has yet been taken about Acklington.

Mr. Beith

I hope that the Under-Secretary of State will take careful note of what I said about the physical location of the mess and about civilians being unaided for considerable periods of time while they are supervising inmates.

Mr. Mellor

I took that point on board. That is why I stressed that no decision has yet been taken. The hon. Gentleman’s point will certainly be looked at. We have a great interest in ensuring that everything goes smoothly at this establishment, that staff are not placed in jeopardy and that offenders do not abscond and make a nuisance of themselves in the neighbourhood. We are anxious to build on the already good relationship in the neighbourhood of Acklington.

The hon. Gentleman referred to education and reported that there is concern about the balance of the education programme. I am satisfied that the programme strikes a reasonable balance between the needs of those inmates who are capable of more advanced studies and those whose educational requirements are more basic. Literacy and remedial classes are available to prisoners who are prepared to make use of them. I know that the education officer at the prison attaches great importance to identifying and encouraging such prisoners. A number of inmates are attending classes of this kind, but we cannot and would not wish to make attendance at classes by adults compulsory. The range of the educational programmes at both Acklington and Castington, and the quality of their library services, are among the best features of the two establishments.

Mr. Beith indicated assent.

Mr. Mellor

I am grateful for the hon. Gentleman’s assent. He also referred to the employment of prisoners. The current employment plan is to provide some 173 industrial workplaces at Acklington: 100 in the tailoring workshop, up to 60 for an engineering or woodwork industry and 13 in the laundry. The present position is that the laundry is fully manned. Some 45 inmates are employed in the tailoring workshop and the aim is to employ the full complement of 100 inmates as soon as the current programme of recruitment workshop preparation has been completed. Prison service industries and farms are currently carrying out an investment appraisal of the engineering and woodwork industry being considered for Acklington. The outcome is likely to be known shortly. I shall let the hon. Gentleman know about that as soon as we have the details.

I share the hon. Gentleman’s concern about the current lack of employment opportunities at Acklington. It is also the case that the Gaydon hangar is not yet fully in use, but the hon. Gentleman may be assured that the prison department is doing what it can to speed up the process of employing inmates and making the best use of the hangar. But it is quite clearly prudent to ensure that the investment of public money in prison industries at Acklington is soundly based. The investment appraisal is designed to ensure that this objective is met.

As for medical facilities, perhaps I should explain that the purpose built hospital at Acklington was designed to serve, and does serve, the populations of the two establishments, which together now hold over 600 inmates. The medical and hospital staff also serve both establishments. I share the hon. Gentleman’s disappointment that it has not yet been possible to bring the in-patient facility into use. Initially there were problems with the internal security and control arrangements, and more recently staffing pressures on the discipline side have meant that local management has been unable to make suitable arrangements for a night patrol in the hospital area, which is physically separate from the sleeping accommodation in the main prison.

However, I understand and am happy to report that these difficulties have now been resolved. It is hoped to appoint a full-time medical officer to Acklington in the near future and that it will then be possible to set an early date for the opening of the inpatient facility to Acklington inmates, although some upgrading of physical security may be required before its use can be extended to in-patients from Castington.

Finally, it is right that I should place in perspective the matters that the hon. Gentleman has raised. Acklington prison and Castington youth custody centre are both developing, expanding institutions. For their staff these plans afford both the prospect of challenging and worthwhile work and the means and resources with which to carry it out.