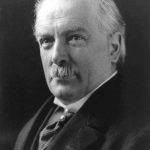

The speech made by David Lloyd George, the then Prime Minister, in the House of Commons on 14 December 1921.

We generally select for the moving and seconding of the Address Members of what I may call budding promise; but we regarded this occasion as being so exceptional that it was thought desirable to select men whose promise had matured into reputation and respect in the House. My hon. and gallant Friend who moved, and my right hon. Friend who seconded, have made speeches worthy of the reputation which they have already won in this House—well-considered, thoughtful, prudent, discreet. There were many difficulties which they avoided. They realised that it was necessary, not merely to carry these Articles in this House, but also to secure the assent of the Irish representatives as well; and all those who take part in this Debate must necessarily be hampered by that knowledge. These Articles of Agreement have received a wider publicity than probably any treaty that has ever been entered into, except the Treaty of Versailles. They have been published in every land.

No agreement ever arrived at between two peoples has been received with so enthusiastic and so universal a welcome as the Articles of Agreement which were signed between the people of this country and the representatives of the Irish people on the 6th of this month. They have been received in every quarter in this country with satisfaction and with relief. They have been received throughout the whole of His Majesty’s Dominions with acclaim. I saw that they were characterised in some quarters as “a humiliation for Britain and for the Empire.” The Dominions of the Crown are not in the habit of rejoicing over acts of humiliation to the Empire, for which they have sacrificed so much. Every article was telegraphed to them as soon as the Treaty was signed and, without a dissentient voice, Governments and Parliaments not merely sanctioned and approved, but expressed satisfaction and joy at the transaction. Every Ally sent through its leading Ministers congratulations to the British Government on the accord—tried friends of ours, not in the habit of being glad when we are humiliated. At home, in the great Dominions of the Crown, among our Allies, throughout the whole of the civilised world, this has been received not merely with satisfaction, but with delight and with hope.

I am very much obliged to my right hon. Friend (Sir Donald Maclean) for the kind words he used in reference to the part which I took, but let me say at once that, in so far as this Agreement has been achieved, it would not have been done without the most perfect collaboration among all the members of the British Delegation. Every one of them worked hard; each of them contributed from his mind and from his resource. The same thing applies—and here I am in cordial agreement with my right hon. Friend—to the part played by the representatives of Ireland. They sought peace, and they ensued it. There were some of my right hon. Friends who took greater risks than I did in signing this Treaty. It will be remembered to their honour. There were men on the other side who took risks. The risks they took are only becoming too manifest in the conflict which is raging at this hour in Ireland, and all honour to them. Not a word will I say—and I appeal to every Member in this House not to say a word—to make their task more difficult. They are fighting to make peace between two great races designed by Providence to work together in partnership and in friendship.

It is very difficult on an occasion like this to knew exactly what to say, what to dwell upon, what one ought to elaborate, what needs elucidation, what you can just leave to the mere Articles to speak for themselves; and there is no greater difficulty for a man who has been immersed in a business for months than to know exactly what to explain. That is the difficulty I am experiencing at the present moment. If the House will put up with me, I propose to expound the general effect of the Articles of Agreement, leaving it to those who take part later in the Debate to answer any criticisms or respond to any inquiries, or to clear up any obscurities which may appear in the mind of any Member of this House. I understand that an Amendment will be moved which traverses practically the whole of these Articles of Agreement, and there will certainly be another opportunity for my right hon. Friend, and probably for myself, to say a few words later on.

The main operation of this scheme is the raising of Ireland to the status of a Dominion of the British Empire—that of a Free State within the Empire, with a common citizenship, and, by virtue of that membership in the Empire and of that common citizenship, owning allegiance to the King.

Mr. R. McNEILL

“Owning allegiance”!

The PRIME MINISTER

And swearing allegiance to the King. [Interruption.] My hon. Friend can make his observations later on.

Mr. J. JONES

They will not be worth much, if he does make them.

The PRIME MINISTER

I will explain as best I can the nature and extent of this transaction. What does “Dominion status” mean? It is difficult and dangerous to give a definition. When I made a statement at the request of the Imperial Conference to this House as to what had passed at our gathering, I pointed out the anxiety of all the Dominion delegates not to have any rigid definitions. That is not the way of the British constitution. We realise the danger of rigidity and the danger of limiting our constitution by too many finalities. Many of the Premiers delivered notable speeches in the course of that Conference, emphasising the importance of not defining too precisely what the relations of the Dominions were with ourselves, what were their powers, and what was the limit of the power of the Crown. It is something that has never been defined by an Act of Parliament, even in this country, and yet it works perfectly. All we can say is that whatever measure of freedom Dominion status gives to Canada, Australia, New Zealand or South Africa, that will be extended to Ireland, and there will be the guarantee, contained in the mere fact that the status is the same, that wherever there is an attempt at encroaching upon the rights of Ireland, every Dominion will begin to feel that its own position is put in jeopardy. That is a guarantee which is of infinite value to Ireland. In practice it means complete control over their own internal affairs, without any interference from any other part of the Empire. They are the rulers of their own hearth—in finance, administration, legislation, as far as their domestic affairs are concerned—and the representatives of the Sovereign will act on the advice of the Dominion Ministers. That is in as far as internal affairs are concerned. I will come later on to the limitations which have been rendered necessary because of the peculiar position of Ireland in reference to Great Britain, and the Army and Navy more particularly.

I come now to the question of external affairs. The position of the Dominions in reference to external affairs has been completely revolutionised in the course of the last four years. I tried to call attention to that a few weeks ago when I made a statement. Since the War the Dominions have been given equal rights with Great Britain in the control of the foreign policy of the Empire. That was won by the aid they gave us in the Great War. I wonder what Lord Palmerston would have said if a Dominion representative had come over here in 1856, and said, “I am coming along to the Conference of Vienna.” I think he would have dismissed him with polite disdain, and wondered where he came from. But the conditions were different. There was not a single platoon from the Dominions in the Crimean War. It would have been equally inconceivable that there should have been no representatives of the Dominion at Versailles or at Washington. Why? There had been a complete change in the conditions since 1856. What were they? A million men—young men, strong, brave, indomitable men—had gone from all the Dominions to help the Motherland in the hour of danger. Although they came to help the Empire in a policy which they had no share in passing, they felt that in future it was an unfair dilemma to impose upon them. They said: “You are putting us in this position—either we have to support you in a policy which we might or might not approve, or we have to desert the old country in the time of trouble. That is a dilemma in which you ought never to put us. Therefore, in future, you must consult us before the event.” That was right; that was just. That was advantageous to both parties. We acceded to it gladly.

The machinery is the machinery of the British Government—the Foreign Office, the Ambassadors. The machinery must remain here. It is impossible that it could be otherwise, unless you had a Council of Empire, with representatives elected for the purpose. Apart from that, you must act through one instrument. The instrument of the foreign policy of the Empire is the British Foreign Office. That has been accepted by all the Dominions as inevitable. But they claim a voice in determining the lines of our future policy. At the last Imperial Conference they were there discussing our policy in Germany, our policy in Egypt, our policy in America, our policy all over the world, and we are now acting upon the mature, general decisions arrived at with the common consent of the whole Empire. The sole control of Britain over foreign policy is now vested in the Empire as a whole. That is a new fact, and I would point out what bearing it has upon the Irish controversy.

The advantage to us is that joint control means joint responsibility, and when the burden of Empire has become so vast it is well that we should have the shoulders of these young giants under the burden to help us along. It introduces a broader and a calmer view into foreign policy. It restrains rash Ministers, and it will stimulate timorous ones. It widens the prospect. When we took part in discussion at the Imperial Conference, what struck us was this, that, from the mere fact that representatives were there from the Pacific and the Indian Ocean, and from other ends of the world, with different interests, the discussion broadened into a world survey. That was an advantage. Our troubles were Upper Silesia, the Ruhr Valley, Angora and Egypt, and they came there with other questions—with the problems of the Pacific, Honolulu, the Philippines, Nagasaki, and Pekin. All these problems were brought into the common stock, and a wide survey was taken by all the representatives of the Empire, who would honour the policy decided upon, and support that policy when it was challenged. They felt that there was not one among them who was not speaking for hundreds of thousands and millions of men who were prepared to risk their fortunes and their lives for a great Empire.

That is the position which has developed in the last four years. If any one will take the trouble—which I took a few days ago—to read Pitt’s speeches on the Union, he will see how this development within the last four years has altered the argument about Union. What was Pitt’s difficulty? His one great difficulty was this: He was in the middle of a great war, a Continental war, which was not going too well, and no doubt our power was being menaced, and menaced seriously. What did he find? He found two co-ordinating Parliaments, each with full, equal powers to declare peace and war, to enter into treaties and alliances, and he said: “This is a danger.” There had been recent rebellion. He never knew what peril might develop out of that state of things. Had he had the present condition of things to deal with, does anyone imagine that that is the course he would have pursued? Had he found that the question of treaties, alliances, peace and war were left, as they are now, to a great council of free peoples, each of them self-governing, and coming together with the Motherland to discuss their affairs and decide upon their policy, what he would have done then would have been to invite Ireland to come to that Council Chamber, to merge her interests and her ideals with the common ideals of the whole of those free peoples throughout the Empire. That is the position.

Ireland will share the rights of the Empire and share the responsibilities of the Empire. She will take her part with other Free States in discussing the policy of the Empire. That, undoubtedly, commits her to responsibilities which I have no doubt here people will honour, whatever may ensue as a result of the policy agreed upon in the Council Chamber of the Empire. That is a general summary of the main proposition which is involved in these Articles of Agreement.

It is all very well to say “Dominion Home Rule” or “Dominion Self-government.” The difficulties only begin there—difficulties formidable and peculiar to Ireland. There are multitudes of people in this country to-day who are made happy by the thought that they have settled the Irish Question, and they are happy because they said a year or two ago that the way to settle it was by Dominion Home Rule. “That settles it.” I can assure my right hon. Friends opposite that they are not alone in this sense of self-satisfaction. But it does not settle it. You do not settle great complicated problems the moment you utter a good phrase about them.

Mr. J. JONES

“I am the man who knows.”

The PRIME MINISTER

Oh, yes, I do. Certainly I do. I have discovered it. There are innumerable letters, resolutions and speeches which have all said: “Try Dominion Home Rule!” They had all one defect in common. They ignored all the obstacles and, therefore, they gave us no counsel as to how we were to overcome them. It is no use giving a general prescription in complicated cases. You may find the same symptoms, but you cannot ignore the constitution of the patient, his temperament, and, above all, his history, because you may find that there are evils in his system which have been left there by earlier imprudences. Therefore, it is no use going to a chemist, and ordering one general prescription. You have to deal with the complications, and you have to deal with the complications in Ireland, attributable to its history and to the imprudences of statesmen. [HON. MEMBERS: “Hear, hear!”] Yes, of both sides.

These are the things that make a settlement in Ireland difficult, and we found them very difficult of solution. I hope we have found the solution. I never like to be too confident or too sanguine when I am talking of Ireland. Therefore, I am not going to say that we have found the specific at last. It has been said so often, but we must try. At any rate, I can see nothing better.

What were the difficulties? There was the preliminary difficulty that the parties were not ready to come together. There was the difficulty that arose from the geographical and strategical position of Ireland. There was no use saying, “You must treat Ireland exactly as you treat Canada or Australia.” There was Ireland, right across the ocean. The security of this country depends on what happens on this breakwater, this advance post, this front trench of Britain. We knew that, and that was one of the greatest difficulties with which we had to deal. There was no use saying: “Apply Dominion Home Rule fully and completely.” We had to safeguard the security of this land. I am only now enumerating the difficulties. The next difficulty was the question of the National Debt and pensions. Every Dominion has its war debt and its pensions. Unless you make some arrangement with Ireland now, Irishmen in Ireland would be the only Irishmen who would escape contribution to the Great War. Irishmen in this country, Irishmen in the Dominions, Irishmen in the United States of America, are all paying their share. Unless there were conditions in our Agreement that Irishmen in Ireland should also bear the same burden as Irishmen anywhere else, they would escape.

The third was the difficulty which arose from rooted religious animosities. I am sorry to use the word “animosities” in connection with religion, but there they are. It is no use ignoring them. They produce fears, I think exaggerated fears, but it is a great mistake to imagine that exaggerated fears are not facts because they are exaggerated. Even the exaggeration is a fact which you have got to deal with as long as it is rooted in men’s minds, perhaps extravagantly accentuated by recent events in North and South. There were the attacks on Protestants in the South. There were the difficulties about turning men out of shipyards in the North. There were these facts, which accentuated old differences, and added new fuel to old flames and stirred up embers. Then there was the question of protective tariffs and of the accessibility of the ports, the possibility of the exclusion of British ships from the coastal trade of Ireland, just as they are excluded in other Dominions. But the greatest difficulty of all was undoubtedly that created by the peculiar position of the north-eastern end of Ireland itself. That had wrecked every settlement up to the present. Those are roughly the peculiar difficulties, the difficulties which are Irish, which are not Dominion difficulties, and before you applied Dominion status you had to deal with each and all of these complicated troubles rooted in the past history of Ireland.

Now I will deal with them. First in regard to allegiance. If anyone challenges what I am saying—and I understand it is going to be challenged—I will defer what I intend to say until an Amendment is moved on that subject. But for the moment I will confine myself to the statement that there has been complete acceptance of allegiance to the British Crown, and acceptance of membership in the Empire and acceptance of common citizenship. I come to the first of the great difficulties—the security of this country if full and complete Dominion Government were conferred upon, Ireland. My right hon. Friend the Member for Paisley (Mr. Asquith) pointed out in his letter to the “Times” that, that meant that they would have complete control over their army and the navy. They could raise any army they liked and any navy they liked. I pointed out over a year ago what that meant. I said that they could in these circumstances raise an army of half a million men. I think that that was rather ridiculed at the time. I have only got to point out two or three facts. The first is that Australia, with practically the same population, has sent that number of men overseas. The second is that during the War Great Britain raised very nearly one-sixth of its population to put under arias. That would have meant 700,000 in Ireland, and my recollection is that Scotland actually raised, with the same population, something like 700,000 men.

There are two objections, apart from the security of this country, to that being permissible. I say that, even from the point of view of the security of this country, there was an element of danger, but there are two objections apart from that. This country has, since the War, taken the leading part in the disarmament of land forces, and taken a leading part in America in the disarmament of naval forces. We were the first power to put an end to conscription. We took a leading part in imposing the abolition of conscription upon our enemy countries in the Treaty of Peace. We could do so because we were setting the example ourselves. But these problems of the disarmament are the problems of the immediate future. How could the British Empire exercise the weight which it ought to exercise in pressing on other countries the importance of reducing these great forces, which had so much to do with provoking and precipitating the war, when in partnership side by side near us we had a country with forces numbering perhaps 500,000 of men all trained for war? That is the international objection.

The second objection is of a different character. If Southern Ireland trained all its young men, and raised these big forces, one can imagine the apprehension that would fill the hearts of men in the North-East of Ireland. They would be driven, if only to give their people a sense of protection, to pursue the same course. You, therefore, would have all the young men of the North-East of Ireland enrolled, trained, and equipped as fighting forces of the North. What would happen? You would have two rival powers, with menacing conditions, and in those conditions an attitude of defence is apt to be distorted into a gesture of menace. Those are conditions in which conflict always begins. It was desirable, in the interests of the Empire, in the interests of the world, in the interests of Ireland herself, that there should be a limitation imposed upon the raising of armaments and the training of armed men within those boundaries.

I now come to the other side, which is put forward by those who think that we ought not to have allowed any armed forces at all. Let my hon. Friends who think that consider what it means. You cannot guarantee law and order in a country unless you have, to support your civilian forces, a certain number of armed men. We think of Ireland as a country concerned merely about Nationalist questions, concerned merely about these conflicts which have been raging during the last few years. But Ireland has exactly the same problems that we have at bottom. In Belfast there were strikes some time ago, and a considerable number of armed men had to be sent there to maintain peace. In my own country, in Wales, we had a great strike. [HON. MEMBERS: “Lock out!”] We had a stoppage of work, an involuntary stoppage of work. A certain number of extreme men were threatening sabotage. The Government felt compelled to send a considerable number of armed men there to maintain order and protect property. You cannot have a Government responsible for law and order, unless you also equip them with the right to raise a certain number of armed men to support the civil authority. That is all that has been done.

The limit is not beyond what is necessary for the purpose. If you take the most sanguine view, the numbers will not exceed, for the whole of Ireland, 40,000 men. That is not an extravagant figure for the maintenance of order in North and South, with all the possibilities of conflict which may arise. I know exactly what the idea of my friends in the North of Ireland is as to the numbers they require, and if they require these numbers in the North of Ireland, it is not too much to say that it would be unfair to say that the Government in the South of Ireland responsible for law and order should get something corresponding, on the population, to those figures.

Sir F. BANBURY

How do you propose to enforce the limit?

The PRIME MINISTER

That is the Treaty—which is the only question now before us. My right hon. Friend enquires, if this Treaty be broken, what shall we do to enforce it? I am quite willing to face that. It is not a question of one Article. It is a question of the whole of the Articles. If Ireland break faith, break her Treaty—if such a situation has arisen—the British Empire has been quite capable of dealing with breaches of Treaties with much more formidable Powers than Ireland. But we want to feel perfectly clear that when she does so, the responsibility is not ours, but entirely on other shoulders.

I now come to the second force—the Navy. With regard to the Navy we felt that we could not allow the ordinary working of Dominion status to operate. Here we had the experience of the late War, which showed how vital Ireland was to the security of this country. The access to our ports is along the coasts of Ireland. For offence or defence, Ireland is a post which is a key in many respects, and though I agree that Ireland is never likely to raise a great formidable Navy which will challenge us upon the seas, I would remind the House that minelayers and submarines do not cost much, and that they were our trouble mostly in the War. Then as to naval accessibility to the ports of Ireland. The use of coastal positions for the defence of our commerce and the British Islands in time of war is vital. We could not leave that merely to good will, or to the general interpretation of vague conditions of the Treaty. Good will has been planted, but it must have time to grow, and it must not be exposed too much to the winds of temptation. Therefore, we felt that where the security of these islands was concerned, we must leave nothing to chance. My right hon. Friend the Member for Paisley has charged me with having stigmatised Dominion Home Rule as lunacy. I never did so—never. My right hon. Friend, had he taken the trouble to read the speech before criticising it, would have seen that. He said some rather unkind things about me recently, but I think that to force him to read my speeches would be too severe a penalty. I am not complaining, except that I think that if he does criticise my speeches, he is in honour bound to read them.

Mr. ASQUITH

I have read them.

The PRIME MINISTER

Then my right hon. Friend’s memory must be very bad indeed. I never stigmatised Dominion Home Rule as lunacy. What I did say was that to allow Ireland the right to raise unlimited forces, which would provoke civil war there, and be a menace to us, to allow Ireland to raise a navy and any craft she chose, when Ireland was so vital to our defence, was lunacy, and I still say so.

Mr. ASQUITH

It is quite clear that the right hon. Gentleman did not read my speech.

The PRIME MINISTER

If my right hon. Friend says now that he did not say that I characterised Dominion Home Rule as lunacy, then I at once withdraw, but his followers certainly have done so, and I understood that he did also. At any rate, let me make it clear, for the benefit of his supporters that I never did say that. I confined the statement purely to the unlimited raising of forces and to the raising of an independent navy.

Mr. ASQUITH

Which I have never proposed or sanctioned.

The PRIME MINISTER

I have read within the last 24 hours a letter which my right hon. Friend wrote to his organ, the “Times.” I will bring it here tomorrow. He will find there a passage in which he makes it perfectly clear that he would leave the army and navy in the same position in Ireland as in Canada.

Mr. ASQUITH

No.

The PRIME MINISTER

For the moment we will postpone the duel till to-morrow. All I say is that if my right hon. Friend did not say so, and assuming that I am right, such a proposal was sheer lunacy. That is only a kind of provisional characterisation of his speech. So much for the military forces of the Crown. What we have done there is this: We felt that the defence of these islands by sea ought to be left to the British Navy. That is better for Ireland and better for England. There is the inherited skill, there is the power, there is the tradition of the Navy, so that the first thing we provided for was that, in the case of war, we should have free access to all the Irish harbours and creeks. If there be war, we cannot wait for discussions between Governments as to whether you can send your ships here or land men there. The decision must be left to the discretion of the men who conduct the operations.

That is safeguarded by these Articles of Agreement. That does not mean that we do not contemplate that Ireland should take her share in the defence of these islands, the defence of her own coast, and by defending her own coasts helping us to defend ours. In five years we propose to review the conditions, and we trust it will then be possible to allocate a certain proportion of defence to Ireland herself. But that is a matter for discussion and agreement. We shall welcome her co-operation just as we welcome the co-operation of the great Dominions in naval defence and in all the other defence that is necessary for the Empire. If there are any questions to be put upon it, I shall be very glad to answer them.

I now come to the question of tariffs. Here I confess that I was very reluctant to assent to any proposition which would involve Ireland having the right to impose tariffs upon British goods, although undoubtedly it was a Dominion right. Ultimately, and only very reluctantly, we assented to this, for the reason that Ireland is more dependent upon Britain in the matter of trade than is Britain upon Ireland. For Irish produce, especially agricultural products, England is substantially the only purchaser. That is certainly not the case in the opposite way. Therefore, the danger of any menace to our trade and commerce from this quarter is one which is entirely in our own hands; but I did think it was very important that there should be a protection against any legislation which would exclude British ships from the coastal trade with Ireland, and that was inserted in the Agreement.

I come now to the more vexed question of Ulster. Here we had all given a definitely clear pledge that, under no conditions, would we agree to any proposals that would involve the coercion of Ulster. That was a pledge given by my right hon. Friend the Member for Paisley when I served under him as my chief. I fully assented to it. I have always been strongly of the view that you could not do it without provoking a conflict which would simply mean transferring the agony from the South to the North, and thus unduly prolonging the Irish controversy, instead of settling it. Therefore, on policy I have always been in favour of the pledge that there should be no coercion of Ulster. There were some of my hon. Friends who thought fit to doubt whether we meant to stand by that pledge. We have never for a moment forgotten the pledge—not for an instant. That did not preclude us from endeavouring to persuade Ulster to come into an All-Ireland Parliament. Surely Ulster is not above being argued with. You cannot hold that arguing a question, and saying that a person ought to take a certain course, is coercing him. If you threaten—if you say you will use the forces of the Crown, that is coercion; but if you say that in your judgement it is in his interests, in the interests of the whole of Ireland, and in the interests of the British Empire, in the interests of the minority in the South, that Ulster should come in, surely that is an argument which we are entitled to use, and entitled to press?

Mr. R. McNEILL

If you use it fairly.

The PRIME MINISTER

I claim that we have used it fairly—quite fairly. We have used every argument in favour of it. I have heard from the benches where the hon. Member for Canterbury (Mr. R. McNeill) sits my right hon. Friend Lord Carson set forward as the ultimate ideal—the unity of Ireland. I have never heard an Ulster leader challenge the proposition that that was the ultimate ideal. I meant to have the quotation before me, but I did not think that would be doubted. If that be the ultimate ideal, was it unfair to Ulster to recommend that they should consider the question? That is all we have done. The refusal of Ulster even to enter into discussion, as long as an all-Ireland Parliament was a subject of discussion, raised artificial barriers in the way of an interchange of views. We could not have agreed to withdraw the discussion of an all-Ireland Parliament from the Conference without breaking it up, and we should not have been justified in breaking it up upon a refusal even to enter into a discussion of the desirability of the proposal. The responsibility was too great, and we could not accept it.

What is the decision we have come to in this Treaty? Ulster has her option either to join an All-Ireland Parliament, or to remain exactly as she is. No change from her present position will be involved if she decide, by an Address to the Crown, to remain where she is. It is an option which she may or may not exercise, and I am not going to express an opinion upon the subject. If she exercise her option with her full rights under the Act of 1920, she will remain without a single change except in respect of boundaries. We were of opinion—and we are not alone in that opinion, because there are friends of Ulster who take the same view—that it is desirable, if Ulster is to remain a separate unit, that there should be a readjustment of boundaries.

Mr. LYNN

No.

The PRIME MINISTER

I stated that there are people who express that opinion, and I think it is wise. Just see what it means. There is no doubt—certainly since the Act of 1920—that the majority of the people of two counties prefer being with their Southern neighbours to being in the Northern Parliament. Take it either by constituency or by Poor Law unions, or, if you like, by counting heads, and you will find that the majority in these two counties prefer to be with their Southern neighbours. What does that mean? If Ulster is to remain a separate community, you can only by means of coercion keep them there, and although I am against the coercion of Ulster, I do not believe in Ulster coercing other units. Apart from that, would it be an advantage to Ulster? There is no doubt it would give her trouble. The trouble which we have had in the South the North would have on a smaller scale, but the strain, in proportion, on her resources would be just as great as the strain upon ours. It would be a trouble at her own door, a trouble which would complicate the whole of her machinery, and take away her mind from building. She wants to construct; she wants to build up a good Government, a model Government, and she cannot do so as long as she has got a trouble like this on her own threshold, nay, inside her door.

What we propose I think is wise for Ulster, namely, that you should have a re-adjustment of boundaries, not for the six counties, but a re-adjustment of the boundaries of the North of Ireland which would take into account where there are homogeneous populations of the same kind as that which is in Ulster, and where there are homogeneous populations of the same kind as you have in the South. If you get a homogeneous area you must, however, take into account geographical and economic considerations. For instance, there is a little area, I believe, of Catholics, right up in the North-East of Antrim, cut off completely from the South. Nobody proposes, because the numbers there would be in favour of joining the South, that that should be taken away from the North and put into the South. You must have regard to economic considerations as well; but taking into account all these considerations, I believe it is in the interest of Ulster that she should have people who will work with her and co-operate with her, and help her along, and not make difficulties, not merely inside her boundaries, but difficulties with her neighbours as well. For those reasons we have recommended a Boundary Commission. It is not for me to say what the result will be, whether it will mean that the area of Ulster will be diminished or increased. There are those who think both, but at any rate, we propose to set up an arbitration. There will be a nominee of the. Northern Government, a nominee of the Irish Free State, and there will be a Chairman appointed by the Government, and we will take care to get a man of distinction and a man whose impartiality will commend itself to all parties alike.

Mr. ASQUITH

This is a very important point. I would like my right hon. Friend to tell us, is the operation of this proposed Boundary Commission to be by counties, or by any specific areas, or merely an enumeration of population?

The PRIME MINISTER

No, no! If my right hon. Friend will take the actual terms, he will find that we avoid giving specific directions of that kind to the Arbitrator. He is there to adjust the boundaries, and he can take into account these considerations.

Mr. ASQUITH

The boundaries as between North and South?

The PRIME MINISTER

As between the Northern community and the Southern. He takes into account the wishes of the inhabitants, but, as I pointed out, if that were the sole criterion, you might take away a little corner of North-East Antrim. Therefore, you have also got to take into account geographical considerations and economic considerations. You have also got little islands of Protestants in Catholic areas, and you must undoubtedly take into account whether a given place is an economic centre for one area or the other. I think I have dealt with the difficulties with which we were confronted.

I now come to the question of machinery, of how these provisions can be carried into effect. There are permanent and provisional arrangements to be made. With regard to the permanent arrangements these must be formulated by the Irish representatives themselves. Here we are going to follow the example which has been set in the framing of every constitution throughout the Empire. The constitution is drafted and decided by the Dominion, the Imperial Parliament taking such steps as may be necessary to legalise these decisions. Any proposal in contravention of this Agreement will be ultra vires. The position of the Crown must, therefore, be assured. Relationship to the Empire must be established, the rights of Ulster safe-guarded, and likewise provisions for the protection of religious minorities must be incorporated. Provisions as to the Army and Navy must also be inserted. Within these limits, Ireland herself determines the constitution of her own Government. Written assurances have been given by the plenipotentiaries that before they do so they are to take into full consultation the representatives of the Southern minority. I believe there have already been interchanges of views between them of the most friendly character. They are most anxious—I am convinced they are most anxious—to do everything in their power to retain the minority within their area. They want their experience, they want their training, they want the help which they can give to reconstruct the Ireland to which they are all attached; and I am convinced that the leaders of the majority in Ireland mean to do all in their power to make it not merely possible for the minority to live there, but to make it as attractive as possible for them to continue their citizenship among them.

Then there are the provisional arrangements. What is to be done before the Constitution is set up? There are two ways of dealing with that.

One would be the status quo, leaving the forces of the Crown there to operate. But that is obviously undesirable once we have arrived at an agreement. There is a danger of incidents occurring which might imperil the whole Agreement. We therefore propose that a Provisional Government should be set up with such powers as are now vested in the Crown. That Government must represent the existing majority of Irish representatives. As soon as that is arranged, the whole responsibility for the Government of Ireland outside the Northern Province would be handed over to this Provisional Government and the Crown forces will be withdrawn.

That is the substance of the Agreement we have entered into. There are such questions as Acts of Indemnity which are vital. We do not want questions to be raised on one side or the other which would involve the courts for years, and which would provoke controversies between the two countries. There must be an Act of Indemnity, and a Bill will be introduced into this House. It is only proposed now to take the ratification or sanction or assent or approval of this document; but a Bill will have to be introduced in another Session to ratify the arrangement, and give it statutory effect. If anything has been overlooked, if anything has to go into this Agreement, that must be agreed to between the various plenipotentiaries. But the introduction of Amendments without assent would undoubtedly break the Treaty, because the other party would not be bound by any alteration made either in one Parliament or the other. What applies to this Parliament equally applies to the Parliament of Southern Ireland. I have no doubt at all there will be Amendments moved there to leave out certain restrictions and limitations and qualifications. Once they are inserted, the Treaty goes. The same thing applies to any Amendment in this Parliament. Unless the wisdom of our entering into this Agreement is seriously challenged, it would only be a waste of the time of this House to enter into a defence of it.

So far there have been but two criticisms, and I will deal very briefly with them. The first is that this is a surrender to rebellion, and is therefore a derogation from the dignity of the Crown and the prestige of the Empire. The best answer to that is the effect which the agreement has had throughout the whole civilised world, and notably in the Dominions. The part played by the Monarch has added dignity and splendour to the Throne.

Sir W. JOYNSON-HICKS

On a point of Order. I am exceedingly sorry to intrude on the Prime Minister. I did not raise this point of Order when two previous speakers were addressing the House, because they were moving and seconding the Address. I now ask your ruling, Sir, as to whether the name of the Monarch can be introduced into a Debate in this House. I submit with great deference that it is one of the oldest and longest standing Rules of Order of this House that no reference whatever should be made to the personality of the Crown or the action of the Crown. In these circumstances, I ask whether it is in order for the right hon. Gentleman or for any other Member in this Debate to refer to the action of the Crown in regard to this matter?

Mr. SPEAKER

I think the hon. Baronet has stated the position of this House just a little too broadly. In moving the Address in reply to the Speech from the Throne, it is not possible to avoid using the name of the Sovereign. Our rule—a very sound one—is that the name of the Sovereign should not be brought into Debates to influence decisions.

The PRIME MINISTER

It is only to that extent I propose to go, and, having regard to the terms of the Address, it is essential I should make that reference. The prestige of the Empire has been enormously enhanced by this Agreement. It has given the Empire a new strength. There was a very remarkable communication which came the other day from an able correspondent at Washington, and I think it worth reading to the House:

“Regarding the Irish settlement strictly from the American standpoint, its effects must be beneficial on Anglo-American relations and ought to bring about a close and firm friendship between England and the United States, which hitherto has been impossible, because all attempts at amity were defeated by Irish malcontents in this country. Ireland has long been an issue in American politics. It has affected elections and controlled policies. It has divided parties. It has defeated treaties, agreements, and co-operation between England and the United States because of the terrorism exercised by the Irish.”

It ends up:

“The ‘New York Times,’ voicing the general approval, states that some politicians in this country will lament that their source of reputation and of livelihood has been taken from them, but nothing can really abate the deep satisfaction with which the entire world will receive the news.”

That is the Washington correspondent of the “Morning Post.” There is a lack of co-ordination there, but it is very creditable to the news columns of that paper. There is no doubt at all that he is one of the ablest correspondents which any paper has got in America at the present time, and that is very well known. It has added to the conviction which the world already possessed that Britain somehow or other always gets over her difficulties. It is dangerous to discuss the ethics of rebellion.

Lieut. – Commander KENWORTHY

Hear, hear!

The PRIME MINISTER

I meant no personal reflection. Is it to be laid down that no rebellion is ever to be settled by pacific means? If the terms are good, are they never to be negotiated with rebels? Whom else could we have negotiated with? This House is the last authority in the world to maintain that proposition. It owes its greatest rights and privileges to concessions made to successful rebels. And may I also point out that the most ruthless repression of any Irish insurrection was effected by the greatest English rebel in history, leading an army of rebels, on behalf of a rebel government, to crush the Irish who had rallied to their legitimate Sovereign. If you take the greatest battle in Irish history—and I am sure my friends from Ulster will forgive me if I allude to it; you might have thought sometimes it was fought only yesterday—it was a battle fought by a British army led by a revolutionary King against an Irish army led by a King who had been deposed by an English revolution. There were more than half, I believe, of the English aristocracy who still believed him to be the rightful occupant of the Throne. There are considerations when you come to discuss rebellion in Ireland which are very difficult to disentangle, and we had better not say too much about them. The same arguments were advanced when there was appeasement of Canada. One of the Bills that was carried through this House was characterised by the “Morning Post” of that day as the “Rebels Reward” Bill. I make my hon. Friends a present of that. That “Rebels Reward” Bill, 70 years later, brought over 500,000 valiant men to our aid in our greatest trouble. The Earl of Chatham when dealing with rebellion in the United States of America, moved a Resolution which ended like this:

“Fully persuaded that to heal and to redress will be more congenial to the goodness and magnanimity of His Majesty and more prevalent over the hearts of generous and free-born subjects than the rigours of chastisement and the horrors of civil war.”

That is equally true to-day. He said, in the course of the speech in which he commended that to the House of Lords:

“It is difficult for a Government, after all that has passed, to shake hands with defiers of the King, defiers of Parliament, defiers of the people. … Mercy cannot do harm. It will seat the King where he ought to be, throned in the hearts of his people; and millions at home and abroad now employed in obloquy and revolt would pray for him.”

Therefore I do not shrink from this settlement. There are those who say we might have done it a year or two ago. Who can say? It is easy for you to see clearly what you can propose, but you must choose your time in proposing it. Statesmanship consists not merely in the wisdom of your proposals, but in the choosing of the right moment. My right hon. Friend the Member for Paisley and I belong in different ranks to the same profession. I belong to the lower and working ranks, and consequently the less remunerated. He knows what it is to settle an action, and he knows it depends upon your choosing exactly the moment. You must not choose it when the parties are full of fight, when they are confident they are going to win, when they are confident, not merely in the justice of their case, but in the invincibility of their counsel. Who can stand against it? That is not the time to settle. You have got to wait until difficulties have cropped up which they had never foreseen, when doubt begins to enter their minds as to the completeness of their victory, when the costs are mounting up, and the only smile is on the face of the solicitor, when they are tired out by pleadings and counter-pleadings and all the delays and wearing mechanism of the law. That is the time. But if you propose too soon, it means not merely that you fail then, but that you interpose obstacles in the way of settling at the right time. You cannot repeat exactly the same terms which have already been rejected—and terms which may be excellent to-day would not have been looked at a year ago—but you cannot repeat them once they have been thrown over. Every counsel knows that, and every statesman ought to know it.

In 1917 we tried a settlement. Representatives of Sinn Fein would not come to the Convention, and for the rest one party would not agree to the unity of Ireland and the other party would not look at anything without it. The result was division. What was ultimately agreed to was not carried by a majority of that Convention. There were moments when we all feared that we proposed a Conference too soon, and if any of those who think that we might have done it a year ago could have just peeped through and seen the last hours which ended in agreement, they would have wondered whether, on the whole, we might not have waited a little longer. You have done it, but only just. I believe that it could not have been done had you not faced Ireland with the accomplished fact of the rights of Ulster. That accomplished fact—by legislation, by the setting up of the Government, by the operation of the Government—it was there to deal with, not in the abstract, not in an argument, not in contention across tables, but in an actual living Government. There are those who still think it could have been done a year or two ago. We do not think so.

Mr. CHAMBERLAIN

Hear, hear!

The PRIME MINISTER

We have got in support of our view this agreement, and can anyone say it could have been reached a year ago? I do not believe it could. But it has been done. I invited here time and again conferences, and those invitations were not accepted. The fact of the matter is that public opinion on neither side was quite ripe. It was only when it came to be realised by everybody that prolonging the agony would only mean more loss, devastation, irritation, and trouble that the moment came when men of reason on both sides said: “Let us put an end to it.” You could not have done it earlier; but here it is, as far as it has gone. We have got this document. [An HON. MEMBER: “A scrap of paper!”]

On the British side we have allegiance to the Crown, partnership in the Empire, security of our shores, non-coercion of Ulster. These are the provisions we have over and over again laid down, and they are here, signed in this document. On the Irish side there is one supreme condition—that the Irish people as a nation should be free in their own land to work out their own national destinies in their own way. These two nations, I believe, will be reconciled. Ireland, within her own boundaries, will be free to marshal her own resources, direct her own forces—material, moral and spiritual—and guide her own destinies. She has accepted allegiance to the Crown, partnership in the same Empire, and subordinated her external relations to the judgement of the same general Council of the Empire as we have. She has agreed to freedom of choice for Ulster. The freedom of Ireland increases the strength of the Empire by ending the conflict which has been carried on for centuries with varying success, but with unvarying discredit, for centuries. Incidents of that struggle have done more to impair the honour of this country than any aspect of its world dominion throughout the ages. It was not possible to interchange views with the truest friends of Britain without feeling that there was something in reference to Ireland to pass over. This brings new credit to the Empire, and it brings new strength. It brings to our side a valiant comrade.

During the trying years of the War we set up for the first time in the history of this Empire a great Imperial War Cabinet. There were present representatives of Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, and India, but there was one vacant chair, and we all were conscious of it. It was the chair that ought to have been filled by Ireland. In so far as it was occupied, it was occupied by the shadow of a fretful, resentful, angry people—angry not merely for ancient wrongs, but angry because, while every nation in the Empire had its nationhood honoured, the people who were a nation when the oldest Dominion had not even been discovered had its nationhood ignored. The youngest Dominion marched into the War under its own flag. As for the flag of Ireland, it was torn from the hands of men who had volunteered to die for the cause which the British Empire was championing. The result was a rebellion, and, at the worst moment of the War, we had to divert our mind to methods of dealing with the crisis in Ireland. Henceforth that chair will be filled by a willing Ireland, radiant because her long quarrel with Great Britain will have been settled by the concession of liberty to her own people, and she can now take part in the partnership of Empire, not merely without loss of self-respect, but with an accession of honour to herself and of glory to her own nationhood.

By this agreement we win to our side a nation of deep abiding and even passionate loyalties. What nation ever showed such loyalty to its faith under such conditions? Generations of persecution, proscription, beggary and disdain—she faced them all. She showed loyalty to Kings whom Britain had thrown over. Ireland stood by them, and shed her blood to maintain their inheritance—that precious loyalty which she now avows to the Throne, and to the partnership and common citizenship of Empire. It would be taking too hopeful a view of the future to imagine that the last peril of the British Empire has passed. There are still dangers lurking in the mists. Whence will they come? From what quarter? Who knows? But when they do come, I feel glad to know that Ireland will be there by our side, and the old motto that “England’s danger is Ireland’s opportunity” will have a new meaning. As in the case of the Dominions in 1914, our peril will be her danger, our fears will be her anxieties, our victories will be her joy.