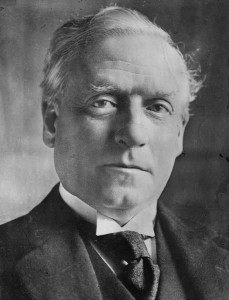

Herbert Asquith – 1887 Maiden Speech in the House of Commons

Below is the text of the maiden speech made by Herbert Asquith in the House of Commons on 24 March 1887.

MR. ASQUITH (East Fife) said, he would ask the indulgence of the House while he stated the reasons that induced him as an Englishman who represented a Scottish constituency, in the interests of Great Britain no less than in the interests of Ireland, to support the Amendment. It appeared to him that the Government were inviting them to a display of trustfulness, not to say of credulity, which might well tax the faith of the most docile and the best-disciplined majority. the Chief Secretary for Ireland had darkly hinted that when the time came for him to introduce his Bill, he would be able to unfold a terrible tale of anarchy and disorder. But up to this moment, after three nights’ hot debate, not a single responsible Minister had condescended to a single specific statement in support of the proposal of the Government. the right hon. Gentleman had contented himself first with general declamation as to the condition of Ireland, and next by appealing to the precedent of 1881. Now that appeal to precedent rested on two assumptions—first, that the state of things now was similar to the state of things existing then—a hypothesis which had been effectually-demolished by the right hon. Member for Mid Lothian (Mr. W. E. Gladstone); and, secondly, that the experiment of 1881, repeated in 1882, was so well justified by experience, so brilliantly fruitful of good results, that at this distance of time—1887—they were bound to follow it as a precedent, blindly, implicitly, without question and almost without argument. He would direct the attention of the House to that assumption. A great deal had been said about the duty of the Executive Government to enforce the law. He entirely agreed with that proposition. In his judgment it was the duty of the Executive not to inquire whether the law was good or bad, just or unjust, but to enforce it in all places, and at all times, without distinction of persons, without discrimination of cases, with undeviating uniformity, and with irresistible strength. [Ministerial cheers.] Hon. Gentleman opposite cheered that statement, but he would ask them, when, in our time, had that view of the duty of the Executive been recognized and acted upon in Ireland? Once certainly, and once only, and that was during Lord Spencer’s administration. Lord Spencer’s hand was heavy, but its pressure was even. Wherever he encountered lawlessness—among Catholics or Protestants, the Moonlighters of the South or the turbulent Orange rabble of the North—who dealt with it in one fashion, firmly, impartially, and effectively. But there was not a right hon. Gentleman now sitting on the Front Bench opposite, with two exceptions—namely, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, who, whatever might be the case now, was then a Member of the Liberal Party, and the Home Secretary, who had not then come to the close of that period of hibernation which separated the two stages of his remarkable political career—with those two exceptions there was not a right hon. Gentleman of Cabinet rank who was not a party, either as principal or accessory, to the most envenomed and bitter attacks upon Lord Spencer’s administration. He would quote for that statement the authority of Lord Salisbury himself, who said that under Lord Spencer’s administration the Nationalist League had grown into power and spread its branches throughout the whole of the country. Next he said that the practice of Boycotting, which up to that time had been comparatively rare, had established itself throughout the country, and, as Lord Salisbury pointed out, that was a practice with which no law, however stringent, could deal and which no Administration, however zealous, could put down. He, for one, did not believe in the plenary infallibility of Liberal Governments, and he did not think the proudest period in the history of the Liberal Party had been that in which it had frittered away in Office pledges which had been given when in Opposition; and, therefore. loyal though he was to his Party and his Leader, he did not think the fact that in 1881 the Liberal Government committed what he considered a colossal and disastrous mistake was any reason whatever why, in 1887, they should, in obedience to a Conservative Ministry, repeat that blunder. It was admitted that, looking at Ireland as a whole, there had been during the last six months less serious crime, whether open or secret, than in almost any corresponding period of her troubled history. What crime there had been was confined to a comparatively limited area in a few counties in the South and West. In those counties they found another phenomenon. It was in those counties that abatements of rent had been most generally refused. It was in those counties that evictions had been most exceptionally frequent in number, and most grave and cruel in their character. It was in those counties that the standard of rents, judged by the reductions made by the Land Commissioners in the course of the last few months, had been abnormally high. As to the prevalence of crime, having regard to these admitted facts, he said deliberately that this was a manufactured crisis. They knew by experience how a case for coercion was made out. the panic-mongers of the Press—gentlemen to whom every political combination was a conspiracy, and to whom every patriot was a rebel—were the first in the field. They had been most effectively assisted on the present occasion on the other side of the Channel by the purveyors of loyal fictions and patriotic hysterics wholesale, retail, and for exportation. The truth, whatever truth there was in the stories, was deliberately distorted and exaggerated. Atrocities were fabricated to meet the requirements of the market with punctuality and despatch; and when the home supply failed, the imagination of the inventive journalist winged its flight across the Atlantic, and he set to work to piece together the stale gossip of the drinking saloons of Now York and Chicago, and eked it out with cuttings from the obscure organs of the dynamic Press. And thus it was that, after six months of comparatively little crime, we found ourselves in the presence of this artificial crisis, and confronted once again with proposals for coercion. They were told—and it was true—that there were certain grave symptoms in the existing condition of Ireland. The National League was assorting its authority throughout the country. In many quarters the practice. of Boycotting was carried on to an extent that was inconsistent with the maintenance of law and good order. There was a disposition on the part of juries not to convict persons who ought to be punished. He made. these admissions; but he asked hon. Members to consider what was the meaning of the facts. His hon. Friend the Member for the Inverness Burghs (Mr. Finlay) declared the other night that he was going to support the measures of the Government because they were measures, not of coercion, but of emancipation—measures to enfranchise the suffering Irish tenant from the tyranny of secret societies. What secret societies? His hon. Friend did not attempt to answer that question; but it appeared that he was referring to the National League. Well, that was no more a secret society than was the Prim-rose League. It was an open association, and reports of the proceedings of all its branches appeared every week in United Ireland. There had been in Ireland and elsewhere secret societies such as the Fenian Brotherhood, the Carbonari in Italy, the Ku-Klux-Klan in the Southern States of America, and the Nihilists in Russia; but these secret societies had been called into existence by measures such as that to be submitted to the House. They had drawn the vitality which enabled them to tyrranize over and terrorize the people by such a policy as the Government were now asking the House to adopt, and in favour of which the Government were asking the House to devote the whole of its time, to the postponement of all the real Business of the nation. Once suspend the guarantees of the Constitution, and take away from the people the privilege of free criticism and of legitimate political agitation, and the consequence was to drive them to those sinister and subterranean methods, which wore destructive of peace and prosperity in every country in which they should exist. The really grave symptoms in Ireland were the existence of Boycotting and the indisposition of juries to convict prisoners. No coercive legislation could have the least effect in diminishing or removing either of those evils. With regard to Boycotting, he was content with the testimony of Lord Salisbury’. It was one of those impalpable things which legislation could not reach, and the only remedy for it was altering the conditions out of which it sprang. The indisposition of juries to convict depended, firstly, on the rooted antipathy and hostility of the class from which the jurors were drawn to the system of law that they were called upon to administer. In the next place, it depended on the unwillingness of men to give evidence against those whom they believed to be in sympathy with the aspirations of the masses of the community. He would illustrate this by the case of the Curtin family. He did not hesitate to say that the treatment to which that family had been exposed was a disgrace to Ireland and a scandal to humanity. But while they should lose no opportunity of denouncing the cruelty of which the Curtin family had been the victims, yet, when they came to practical legislation, they must consider the real meaning of what had occurred. What was the crime in the eyes of the people which the Curtin family were expiating by this terrible social ostracism? It was not that the head of the family shot and killed the leader of the band of marauders who invaded his house by night. It was because the sons and daughters went to Cork Assizes and gave evidence against the persons concerned in that crime. He was not defending or palliating that course of conduct, but they were sitting there as legislators, and not as moral censors. They had to consider what would he the result of their legislation. From actual violence and outrage, and even from open insult, the Curtin family had long since been protected. [“No, no!”] He was speaking of facts which he had personally investigated. Did hon. Members imagine that by the legislation which Her Majesty’s Government were going to propose, they would be able to transmute the social atmosphere in which those people lived and which rendered such treatment of them possible? Suppose they enlarged the powers of the magistrates; suppose they deprived the jurors of their share in the administration of the law; suppose they made punishments more severe; did they imagine that in that way they would increase the disposition of the peasantry of Ireland to come forward and give evidence? Not oven a drum-head court-martial could convict without testimony proving the guilt of the accused. The difficulty which they had to provide for was the difficulty which arose from the fact that the great mass of the population in Ireland were alienated from the law, and had no sympathy with its administration. We were not unfamiliar in this country with the very state of things which existed in Ireland. There was nothing novel in the symptoms. They had been witnessed in every country whenever the state of the law had not been in harmony with the wishes of the people. In the early part of the present century, in the days when it was the custom for the Attorney General to file, as a matter of course, information for seditious libel against political opponents, in vain did the Judges direct that juries had no alternative but to convict. In the teeth of the evidence, and in the face of the direction of the Judge, the jury acquitted the prisoner. It was truly an extraordinary thing that at this time of day the Government, dealing with a well-known form of social and political disease, should come to the House and repeat the catch-words of the Metternichs and Castlereaghs as if they were the latest discoveries of political science. They wore told that, after passing this Coercion Bill, the Government were going to give the Irish people a dose of remedial legislation. The procedure of the Government reminded him greatly of that enterprising speculator in the days of the South Sea Bubble who invited the public to subscribe their money in support of a scheme, the particulars of which were to be disclosed subsequently. History did not record that any dividends were ever paid on the capital so subscribed. He did not wish to impugn the good faith of the Government, and he dared say that they believed in the efficacy of the Land Bill which they were to introduce. At present, however, very little was known about that Bill. They knew that it was to provide for the extension to leaseholders of the benefits of the Land Act. That was a provision borrowed from the hon. Member for Cork (Mr. Parnell). It was further believed that the Bill would provide for the application of some of the equitable provisions of the Bankruptcy Act to the cases of a certain class of tenants. The road to prosperity for these tenants was in some way or other to He through the portals of the Bankruptcy Court—in truth a very encouraging prospect. Then they know that this remedial legislation was in the first instance to make its appearance in “another place.” That was a very significant fact. He was far from being disposed to intrust the Government with exceptional powers for the enforcement of the law on the chance, the very remote chance, that some day or other, this year or next, or on the advent of the Greek kalends, that august Assembly, which in the last 50 years had mangled and mutilated every proposal for the remedy of the grievances of Ireland, might be coerced or persuaded into acquiescing in an equitable solution of the Irish agrarian question. The Chancellor of the Exchequer not long ago, with what was then his habitual caution, declined to give a blank cheque to Lord Salisbury. He thought that they might profit by the right hon. Gentleman’s example; and the liberties of a nation being at stake, reasonably decline to honour this very serious draft upon their political credulity. He quite understood that there were hon. Members near him who took a very different view of the matter. Those hon. Members were compelled by the circumstances of their position to an exercise of faith which a very short time ago they would have been the first to ridicule and condemn. It was, perhaps, excusable in them, that under the stress of compromising memories—memories of the day when they were wont to declare “that force was no remedy,”—memories of the days still more recent when they denounced the wickedness of Irish landlords, and the more than Polish abominations of Castle rule—it was, perhaps, excusable in them that they should clutch at any pretext, however desperate, which might seem to reconcile their present with their past, He did not know who was the casuist of the Liberal Unionist Party. In that compact and complete organization he felt sure that a place must have been found for a director of consciences. “Whoever he was, his time must just now be pretty well occupied. But as for the poor Separatists “the intellectual scum of what was once the Liberal Party,” they might be thankful that they had not to exercise their humble faculties in the attempt to explain how they could vote for a Coercion Bill in the hope that some day or other, in some way or other, remedial measures might be introduced. In the course which the Party opposite were about to take, were they not either going too far or not going nearly far enough? Let them consider what would be the position of Ireland, the condition of government in that country under the system which they were about to introduce—representative institutions upon the terms that the voice of the great majority of the Representatives of the people should be systematically ignored and overridden; the right of public meeting tempered by Viceregal proclamation; trial by jury with a doctored and manipulated panel; a free Press subject to be muzzled at the caprice of an official censorship; Judges and magistrates in theory independent of the Crown, but, in fact, by the tradition and practice of their office inextricably mixed up with the daily action of the Executive. What conceivable advantage could there be either to Ireland or Great Britain from the continuance of this grotesque caricature of the British Constitution? There was much virtue in government of the people, by the people, for the people. There was much also to be said for a powerful and well-equipped autocracy. But, between the two there was no logical or statesmanlike halting-place. For the hybrid system which the Government were about to set up—a system which pretended to be that which it was not, and was not that which it pretended to be—a system which could not he either resolutely repressive or frankly popular—for this half-hearted compromise there was reserved the inexorable sentence which history had in store for every form of political imposture.