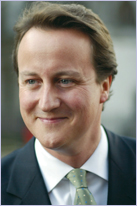

David Cameron – 2007 Speech on Public Services

Below is the text of the speech made by David Cameron, the then Leader of the Opposition, on 26 January 2007.

A few months ago Britain was told that the Conservative Party was taking its lead from a certain Guardian columnist. I’m very pleased that the Guardian is also prepared to listen to the Conservative Party.

The public services are at the heart of my vision for Britain. In recent years the Conservative Party has acquired a reputation for indifference to the public services. This was quite wrong – especially given the origin of the public services.

It was a Conservative, Rab Butler, who introduced free secondary education for all in 1944. And in the same year it was a Conservative health minister, named Henry Willink, who published a White Paper called “A National Health Service”, outlining a plan for universal, comprehensive healthcare, free at the point of need.

Lest anyone imagine I don’t admire Winston Churchill’s social policy, let me quite him from the 1945 election: “Our policy is to create a national health service to ensure that everybody in the country, irrespective of means, age, sex, or occupation, shall have equal opportunities to benefit from the best and most up-to-date medical services available.”

In fact the NHS is a truly non-party institution. It was inspired by a Liberal – William Beveridge – planned by a Conservative – Henry Willink – and introduced by a Labour minister, Nye Bevan.

Of course the three parties, then and now, have disagreements about how the NHS should be organised. But we all share an absolute belief in its aims and values. It is one of the institutions – like the monarchy or the BBC – which binds us together as a nation. And the same goes for all our great public services.

The shape of the public services

The idea at the heart of the modern Conservative approach is social responsibility. And public services are one of the clearest expressions of what that means. Social responsibility is based on a conviction that we’re all in this together. That government doesn’t have all the answers, and that society is not the same thing as the state. Social responsibility gives us a clear direction in shaping the policy agenda that will address the big challenges Britain faces.

We need to advance civic responsibility, transferring power and control to people and institutions at the local level. We need to encourage and incentivise greater corporate responsibility, to help tackle issues from climate change to obesity.

We must promote personal responsibility, recognising that our freedoms come with duties attached, and that we have collective obligations as well as individual rights.

And perhaps most importantly in respect of public services, we must enhance professional responsibility, trusting in the commitment and expertise of you and all your many thousands of colleagues working in our great public services.

Public services, open to everyone in the community, governed by rules held in common – these are the institutional manifestations of social responsibility.

But today I want to question whether the shape of our public services is the right one for this purpose.

To do this I have to go back to the beginning. We often date the origins of our public services to the end of the second world war sixty years ago.

In fact, our public services are, in their inspiration, much older than that. I believe that the ideas which went into the design of our public services are now fully a century out of date.

Let me explain. Ideas take time to germinate. It is often the intellectual theories of an earlier age that influence the practical decisions taken in the present. And so it was that our modern health, housing and education systems were designed, in the middle of the twentieth century, by men and women who were under the intellectual influence of the generation who came before them.

Britain’s public services owe their origins to the era from Bismarck to Henry Ford. It was Bismarck who, in Germany in the late 19th century, first used the power of the state to create mass welfare services, controlled from the centre. And it was Henry Ford who first mechanised production on a mass scale, using assembly lines to create higher volumes of output.

The middle years of the 20th century, when our public services were designed, were dominated by the Bismarckian idea of the role of the state, and the Fordist idea of how production should work. Rather than the mutual and self-help traditions of an earlier generation, a new intellectual climate took hold which stressed centralisation, standardisation and scale. Some would argue that these ideas were right for their day but they are wrong for our day.

Let me start with health.

Health

Michael Foot, in his biography of Nye Bevan, explained how Bevan was inspired by the great steps forward in public health made in the 19th century, especially slum clearance and sanitation.

These were the achievement of government – and Bevan applied that lesson to the design of the new health service. The NHS as it emerged was built on Fordist lines. The conscious or unconscious inspiration behind many of our modern hospitals is an assembly-line, dedicated to producing the highest volume of ‘units’ – that is, patients treated – in the shortest possible time.

Now I think this was the right model for 1946. In those days ‘healthcare’ usually meant serious, infrequent medical interventions, often surgery. And the factory model is still helpful today in the case of routine treatments such as hips and cataracts. But in general the very meaning of healthcare is different. So the model of delivery needs to change.

These days healthcare doesn’t always mean one or two visits to hospital in an individual’s life – it often means constant care, often self-managed.

There are 17 million people in Britain with long-term conditions. For them healthcare is not a passive event, but an active process, depending on personal factors such as relationships with doctors and family as much as medical factors.

Not just the hospital consultant, but also the GP, the practice nurse, the pharmacist, the care worker… these are the professionals who deliver healthcare.

In spite of government talk about the importance of primary care and local treatment many see their local health service being dismembered,

Community hospitals are being closed to make way for new, regional, super-hospitals. I think this runs directly counter to what modern healthcare means, and what people themselves want.

Prisons

The same Fordist assumption dominates another of the great public services – the prison system.

Perhaps ‘public service’ is the wrong word here – we don’t exactly want comprehensive, universal access to prisons. Our prisons are responsible for people and they operate under designs and rules laid down by government.

Those designs and rules have their intellectual origins in the 19th century. In fact our modern prisons take their very architecture from the Victorian era. Prison design has hardly changed in over 150 years – large buildings on a radial or block model, designed to keep prisoners in physical isolation.

Again, this was an enlightened and progressive step for the time, and a major improvement on the terrible conditions of pre-Victorian prisons. But today the effect is that 80 per cent of prison manpower is dedicated to security, and only 20 per cent to education, training, drugs treatment or rehabilitation.

I think that’s the wrong ratio and it reflects an out-of-date understanding of criminality and human motivation. Of course we need to maintain the highest standards of security – that, after all, must always be the top priority of the prison service. And yet I believe that we and maintain security and improve the rehabilitative work that prisons do.

Instead of institutions designed to keep offenders in isolation and idleness, we need prisons where criminals undertake a full day’s work, education or training.

Over the last decade, re-offending rates have increased substantially. The current government has shown a failure of planning because they did not build the prison places required. There has been a failure of policy, because re-offending rates have gone up. And there has been a failure of political will because even when they knew there was a problem, nothing was done about it.

Education

Then there is education. Again, we take our idea of education from the era of Bismarck and Ford. Our modern secondary school system began with Rab Butler’s Education Act in 1944. This sought to preserve the independence and variety that already existed in education, while arranging for universal access.

The real change came with Dick Crossman’s comprehensive schools in the 1960s. Universal education is one of the great achievements of modern times. And yet I do not believe that universal education has to mean standardised education. Comprehensive education should not mean all children, of all aptitudes and interests, being taught together in the same classes, studying the same subjects at the same pace.

Real education involves a recognition of difference among people. Schools should help each child work towards his or her best self – not force every child into the same mould. There is a wealth of evidence and new thinking pointing the way to a better system of educating children. A system based on the individual aptitudes of individual children, yet which recognises the crucial role of sociability and shared endeavour.

This is why I am committed to an extension of setting and streaming within schools. A more plural understanding of how education works requires a more plural education system itself – one which welcomes a diversity of schools.

I recently visited a Muslim girls’ school called Feversham College in Bradford. When I first walked in I was rather taken aback by the sight of rows of girls dressed in jilbabs. But those girls were confident, articulate… in a word, well-educated. The experience confirmed the vital importance of schools having a clear ethos – and I see no problem with that ethos being a religious one.

I am pleased that, after years of preaching the need for standardised education, Labour has come to realise this. That is why I was proud to support the Education Bill that went through Parliament last year.

We need to go much further, but Labour have made a start.

Housing

Next, a word about housing. This was another of Nye Bevan’s responsibilities after the war. And he made great efforts to ensure ‘dignity’ – that key Bevanite word – for the families who would live in the new housing.

But the demand of the day was volume. That meant standardisation of design and cheap construction. Partly because of his wish for high quality homes, Bevan never built enough of them. Harold Macmillan, by contrast, built 300,000 homes a year – but it was not possible to ensure that each house was comfortable and beautiful, let alone different from its neighbours.

The principle of mass production and standardisation really took off in the 1960s and 70s, with the results we are all familiar with.

Architects under the influence of Corbusier, the Henry Ford of architecture, built blocks which resembled not so much factories, as warehouses for the efficient storage of human beings.

Surely everyone now recognises the need for better housing design – and in many communities across the country, we are seeing real progress.

And yet we are in danger of reverting to the Macmillanite model: not high-rises, but rabbit hutches – ugly mass produced boxes.

There is an urgent need for more affordable homes. The Government-funded scheme for low-cost home ownership has helped only 40,000 people to buy a stake in their homes in the past seven years, while the estimated demand is for 60,000 households per year.

We need to stimulate real innovation in design and the growth of low-cost housing which is nevertheless beautiful to look at and comfortable to live in.

This requires a great liberalisation of the planning rules and building regulations.

Professionals

So that is how our public services are designed and built. The emphasis on volume. The large centres of production, achieving standardisation and economies of scale. The user comes to the producer, and the producer is in charge. All in all, a sense on the part of the individual that public services are something that happens to you, not with you, let alone – God forbid – by you.

Part of that is the way that the different public services seem to exist in parallel worlds. Because of the focus on large units of production, they tend to operate in silos. The other day I had a meeting with a constituent of mine with very impaired mobility. He always needs someone to help him get out of bed and move around. He explained how if his wife is delayed away from home and he needs to move, he has no option but to call an ambulance, at enormous cost to the taxpayer and at real risk to people in life-threatening situations.

This is crazy – all he needs is a care worker on call who can come out in an emergency. But social care and health are funded separately and organised separately, and one does emergency call-outs and the other doesn’t.

He has no power to organise his own emergency cover – he has to take what the public services offer and make the most of it.

Now, you often hear that public services suffer ‘producer capture’ – that they work according to the convenience of the producers, not the users they actually exist for.

And in a sense – as my constituent’s story reminds us – that’s true. And yet it is a sad irony that a system which disempowers the user, also seems to disempower the front-line professional as well.

It is a tragedy that public service professionals are among the least satisfied people in the labour force.

And why is this? Because the attempt to create standardised units of production reduces producers to assembly-line workers.

Their vocation is stifled by the demands of a job that rates conformity over innovation. No wonder so many young professionals leave the public services each year.

The New Jerusalem

So I hope I have demonstrated that the design of our public services is out of date. They too often reduce the individual user to the status of a unit, and they disempower the professionals whose vocation is all that makes public services work.

Now I want to briefly sketch the outline of an alternative design.

This alternative is – if I may borrow from the socialist phrase-book – the New Jerusalem: the liberal-conservative ideal.

It involves a diversity of independent, locally accountable institutions, providing public services according to their own ideas of what works and their own experience of what their users want.

It involves a government which acts as a regulator of services, not a monopoly provider – monitoring service standards on behalf of the public, but not always delivering them.

As George Osborne has said, it involves a Treasury which acts as a department for value for money, rather than trying to run every department and public agency from the centre.

It involves, most of all, individuals and families who are empowered with choice. Pluralism on the supply side is matched with freedom on the demand side. The public become, not the passive recipients of state services, but the active agents of their own life.

They are trusted to make the right choices for themselves and their families. They become doers, not the done-for.

Responsible, engaged, informed – in a word, adult. And out of this messy creativity, this multitude of personal choices, comes what we all – left, right and non-aligned – want for our country.

Great public services for all. Decent local schools, which everyone, rich and poor, Muslim and Christian, wants to send their children too.

Housing which leads the world in beauty, in environmentalism, in comfort. Prisons which work, not just at keeping criminals off the streets, but at returning them to the streets reformed and healthy and employable. Local hospitals which are the envy of the world – but not the envy of the neighbouring town, because all hospitals in Britain reach the highest standards.

And this is the great paradox – out of freedom, comes equality. Those who oppose diversity argue that it will lead to inequalities. Yet surely we must accept that the attempt to eliminate inequality by central planning has failed. True equality is not the formal and oppressive standardisation of Fordism, but the natural balancing-out that comes from diversity.

The road to the New Jerusalem

So much for the theory. The most important point I want to make today is this. For some on the right there is nothing easier, or more enjoyable, than describing our New Jerusalem – this paradise of pluralism and freedom and choice.

Indeed, many of my critics on the right earn a living doing just that – describing paradise, and expressing astonishment that I can’t see it too.

Well of course I can – but I aspire to lead the country, not just write about it. And that means I have to take the country as it comes. We cannot always reach our goal as the crow flies. We have to walk to Jerusalem, along a difficult and winding road. We need a clear direction and a relentless focus on the destination – but we have to adapt to realities on the ground.

It will take a long time and it will be difficult – but that is the only way to get there safely. In 1867, after he had secured the passage of the Reform Bill enfranchising working class voters for the first time, Benjamin Disraeli said this:

“In a progressive country, change is constant; and the great question is, not whether you should resist change which is inevitable, but whether that change should be carried out in deference to the manners, the customs, the laws and the traditions of the people, or in deference to abstract principles and arbitrary and general doctrines.”

That is the spirit in which I approach the reform of the public services. I take inspiration from an earlier phase of reform – the changes to trade union law in the 1980s. Big bang reform was a failure. One-step-at-a-time trade union reform was a great success. Ferdinand Mount has called this the “long runway approach to political change”, and the alternative “vertical take off followed by crash landing”.

He talks of “the virtues of slow politics. Like slow food, it tastes better.” So yes to change – urgent change in some cases, change to address serious problems. But change in a way that works – and lasts. And change that is in deference to the manners and customs of the people who work in the public services and the people who use them.

Because it is people who matter most. This is not political flannel – it is a vital principle of management and reform. Even if the design and the structures of an organisation are imperfect – and I think they often are in the case of our public services – they often work nonetheless, because the people who inhabit those structures make them work. And if we suddenly shifted to a perfect design, a perfect structure, but didn’t bring the people with us – the new system would work less well than the old one.

That is why I believe there is so much unhappiness in the public services at the moment, and why Mr Blair and Mr Brown are finding that their reforms aren’t working.

It is not enough for reforms to be right in principle – they have to work with the grain of the professionals.

Accepting the legacy

So let me finish by setting out some simple ideas for the sort of change we want to pursue. Overall, we will avoid making the great mistake of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown.

They came to office with great enthusiasm for the public services – but little idea of what to do with them.

The first two terms were wasted in first abolishing, then partially reinstating, the reforms the previous Government had introduced.

We will not tear up the legacy we receive from Labour. In each of the public services I have mentioned, there are reforms Mr Blair and Mr Brown have introduced that we would want to keep and improve.

In healthcare, we will keep Foundation Hospitals, and move over time to a position in which all hospitals have their freedoms.

We will keep independent delivery of some NHS healthcare, and Payment by Results, and extend these reforms in a way that enhances the professional responsibility of the NHS workforce.

We are committed to independence for the NHS, to take politicians out of day-to-day management; and we will improve the way objectives are set.

We will remove the top-down targets that distort clinical judgments and focus on health outcomes, not medical processes.

In education, we will keep City Academies and trust schools, and take these reforms further. We want to look at current VAT regulations which discourage City Academies from opening their facilities to the community.

We believe schools should be allowed to insist that parents sign Home School contracts which reflect the ethos of the school.

And we will further reform the supply side, so that a greater range of school places are available to parents.

In housing, we will keep the Decent Homes Initiative and maintain the emphasis on more affordable homes.

We will go further, changing the planning rules to allow for more affordable homes and more innovation in design.

We want to see an extension of the right to buy which saw so many families become homeowners in the 1980s.

And in penal policy, we will keep the purchaser-provider split that has been introduced under NOMS.

I also think that the Government is right to try to bring the prisons and probation services much closer, and introduce end-to-end management of each offender by a single caseworker. We want to build on these reforms to put rehabilitation at the heart of penal policy.

System entrepreneurs

So the challenge for us is not to design some grand new structures for the public services – but to make what we’ve got, work properly; and to put in place the systems which will eventually lead to the natural evolution of structures.

To use a medical metaphor: just as modern healthcare is less about major surgery and more about health management, so our reforms should be.

I don’t want to carve up the public services, as if they were laid out unconscious on an operating table.

I want to introduce antibodies into their bloodstream, antibodies which by natural and organic processes find their target and do their work.

It’s often the case in large organisations that there is a number of choke-points, places where relationships don’t work properly.

In the prison service there is often a choke point between prison education departments and the officers responsible for security.

In healthcare, the consultants often need to communicate more with the nurses, and the GPs need to work more closely with the pharmacists.

Parents and teachers often seem to have an adversarial relationship in education. And so on.

I want us to introduce agents into the system to solve these choke-points. I have spoken before about system entrepreneurs – people expert at devising system solutions to organisational and social problems.

There are many system entrepreneurs in the public sector and civil service already – but I believe we need to widen the pool of talent we can draw on.

I would like to see public agencies inviting professionals from other disciplines in to help remove the choke points that stop them working effectively.

Let me give you an example. Earlier this week I visited the Christchurch Family Medical Centre in Bristol. The site includes an NHS surgery and a pharmacy. Now I am convinced that we could see far more co-operation – and co-location – between GP clinics and pharmacies. It is estimated that around half of all GP visits are unnecessary – and the problems in primary and community care often lead to unnecessary hospital visits too.

Patients with diabetes or asthma should never have to go near a hospital – they could be treated jointly by their GP and a pharmacist.

As I saw in Bristol, there are already excellent experiments in GP-pharmacy co-operation, and the Government has said it will support such initiatives.

But it’s not happening on anything like the scale it needs to. There is clearly a system failure – or failures – preventing this. It is as likely to be a cultural problem as a structural one, and the result of a whole set of local circumstances rather than a single national policy.I do not believe we need a huge Whitehall-led reorganisation to make this simple and necessary change take place.

GPs and pharmacists rarely have the time, or the skills, to sort out system failures themselves. We need to send systems entrepreneurs in, at the local level and in Whitehall, to identify what’s going wrong and put it right.

This is not about imposing a new blueprint, re-engineering the structures on the drawing board. It is about recognising where the problems are and allowing professionals the opportunity and the incentive to resolve them.

Community care

And here’s another idea – an even bigger one. As I have been saying, healthcare is increasingly delivered in primary and residential settings and even in the home.

It is increasingly ‘owned’ by patients themselves. But there are two major challenges to local care. One is the threat to community hospitals, which ministers tell us are often under-occupied and over-expensive.

148 community hospitals have closed or downgraded or are threatened with closure. The other is the shortage of affordable places in care homes – since 1997 700,000 people have had to sell their homes to pay for care.So the answer to the problem – over-capacity in community hospitals and under-capacity in care homes – seems straightforward.

Unite them. Break down the barriers between healthcare and social care at the local level, by combining a community hospital and a care home in one organisation.

Now, there are practical difficulties here – not least the divide in funding arrangements between NHS and social services.

And there are structural changes that would need to happen, either immediately or in the future, to facilitate such a reform on a large scale – not least allowing community hospitals to move out of PCT ownership and become charitable trusts or foundation trusts, with proper freedom and local ownership.

But even in the current system, change is possible.

I know this combined hospital-cum-care home can work because I got the idea from a real example – in Chipping Norton in my constituency.

This shows the potential for innovation and change that already exists in the public sector.

Individual budgets

There are further measures we can introduce to break down the divide between health and social care. The constituent I mentioned earlier, who finds himself caught between the two services, is perfectly capable of organising his own care.

He just needs control over the money that is currently spent on his behalf. We have started moving towards this arrangement with the system of direct payments. But I believe we need to go further. We need to simplify Direct Payments by combining an individual’s entitlements to community healthcare and social care into a single budget. That way patients can commission their care from the providers of their choice, on the terms that suit them. These reforms – combining care homes and community hospitals, combining healthcare and social care entitlements – are big ideas.But I believe they can work because they reflect the need that is apparent on the ground, and because they represent the principle of local institutions catering to empowered citizens.

There are many ideas like this, floating around and waiting for action. We need to free up the supply side in education – why is it so hard for a school to grow, or for a new school to open? What are the technical changes that we need to introduce to stimulate greater diversity in education?

We need to get probation officers working in prisons, getting to know their clients before they are released. Why isn’t this a widespread practice?

What cultural or organisational changes are necessary – in national legislation and in local practice?

We need to involve residents in the maintenance and development of housing estates – why are we still so impressed when this actually happens?

What are the right mechanisms for encouraging this? Many of these ideas will require major, structural reform – but not immediately, and never in a way which upsets working practices and relationships that work.

I’d like to see as much ad hoc, local innovation as possible – and I’d like Whitehall and local government actively to sponsor it by assisting with systems enterprise.

That way, when we do move towards a more liberalised structure, the necessary attitudes and working practices have already taken root.

I do not pretend there are no tensions to resolve in our thinking about public service reform. There are – not least the essential tension between greater localism and professional autonomy on one hand, and the need to ensure higher standards through national policy on the other.

One way through is to recognise that with more responsibility and freedom, must come more accountability – accountability not to government but to the users of the service.

And so we need a new contract with the professionals.

Government will strip out targets and top-down control – if you put in place proper professional standards.

We should give front line staff more discretion – but have higher expectations of them too. So as we move forward in our policy review, developing the detailed solutions to the many complex challenges of public service improvement, I hope you can see clearly where the modern Conservative Party is coming from.

We do not want to arrive in government as Labour did, with good intentions but no clear strategy and no considered reform plan.

We do not want to waste time, energy, resources and – vitally – the goodwill of those who work in public services, with reforms that go first in one direction and then another.Our guiding principles are clear, based on our belief in social responsibility. In place of manic reform at a pace that does more harm than good, a more patient approach that avoids lurching from one direction to another.

In place of centralisation, a real commitment to local decision-making. In place of top-down instruction, empowerment of bottom-up innovation. In place of targets that measure processes, a focus on objectives that measure outcomes. Above all, trust in the professionalism of those who devote their lives to serving the public. We will give you the responsibility you deserve, so you can give the people of this country the public services they deserve.