The Book of A History of Parliamentary Elections and Electioneering in the Old Days by Joseph Grego, published in 1886. This book was made available by Project Gutenberg. An HTML5 version is available on their website at https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/52156/pg52156-images.html.

The Project Gutenberg eBook, A History of Parliamentary Elections and

Electioneering in the Old Days, by Joseph Grego

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: A History of Parliamentary Elections and Electioneering in the Old Days

Showing the State of Political Parties and Party Warfare at the Hustings and in the House of Commons from the Stuarts to Queen Victoria

Author: Joseph Grego

Release Date: May 24, 2016 [eBook #52156]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A HISTORY OF PARLIAMENTARY

ELECTIONS AND ELECTIONEERING IN THE OLD DAYS***

E-text prepared by MWS, Wayne Hammond, and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made

available by Internet Archive/American Libraries

(https://archive.org/details/americana)

Note: Project Gutenberg also has an HTML version of this

file which includes the original illustrations.

See 52156-h.htm or 52156-h.zip:

(http://www.gutenberg.org/files/52156/52156-h/52156-h.htm)

or

(http://www.gutenberg.org/files/52156/52156-h.zip)

Images of the original pages are available through

Internet Archive/American Libraries. See

https://archive.org/details/historyofparliam00greg

Transcriber’s note:

Text enclosed by underscores is in italics (_italics_).

Text enclosed by equal signs is in bold face (=bold=).

A carat character is used to denote superscription. A

single character following the carat is superscripted

(example: y^e). Multiple superscripted characters are

enclosed by curly brackets (example: hon^{ble}).

A HISTORY OF PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS

AND ELECTIONEERING IN THE OLD DAYS

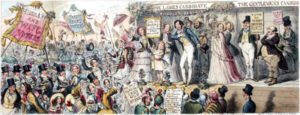

[Illustration: “THE RIGHTS of WOMEN” or the EFFECTS of FEMALE

ENFRANCHISEMENT]

A HISTORY OF PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS

AND ELECTIONEERING IN THE OLD DAYS

Showing the State of Political Parties and Party

Warfare at the Hustings and in the House of

Commons from the Stuarts to Queen Victoria

[Illustration: CANDIDATES ADDRESSING THEIR CONSTITUENTS.]

Illustrated from the Original Political Squibs, Lampoons

Pictorial Satires, and Popular Caricatures of the Time

by

JOSEPH GREGO

Author of “James Gillray, the Caricaturist: His Life, Works, and Times”

“Rowlandson, the Caricaturist: His Life, Times, and Works,” etc.

London

Chatto and Windus, Piccadilly

1886

[The right of translation is reserved]

“I think the Tories love to buy

‘Your Lordships’ and ‘Your Graces,’

By loathing common honesty,

And lauding commonplaces....

I think the Whigs are wicked Knaves

(And very like the Tories)

Who doubt that Britain rules the waves,

_And ask the price of glories_.”

W. M. PRAED (1826).

“A friend to freedom and freeholders--yet

No less a friend to government--he held

That he exactly the just medium hit

’Twixt place and patriotism; albeit compell’d,

Such was his sovereign’s pleasure (though unfit,

He added modestly, when rebels rail’d),

To hold some sinecures he wish’d abolish’d,

But that with them all law would be demolish’d.”

LORD BYRON.

PREFACE.

Apart from political parties, we are all concerned in that important

national birthright, the due representation of the people. It will be

conceded that the most important element of Parliaments--specially

chosen to embody the collective wisdom of the nation--is the legitimate

method of their constitution. Given the unrestricted rights of

election, a representative House of Commons is the happy result;

the opposite follows a tampering with the franchise, and debauched

constituencies. The effects of bribery, intimidation, undue influence,

coercion on the part of the Crown or its responsible advisers, an

extensive system of personal patronage, boroughmongering, close or

pocket boroughs, and all those contraband devices of old to hamper

the popular choice of representatives, have inevitably produced a

legislature more or less corrupt, as history has registered. Bad as

were the workings of the electoral system anterior to the advent

of parliamentary reform, it speaks volumes for the manly nature of

British electors and their representatives that Parliaments thus basely

constituted were, on the whole, fairly honest, nor unmindful altogether

of those liberties of the subject they were by supposition elected to

maintain; and when symptoms of corruption in the Commons became patent,

the degeneracy was not long countenanced, the national spirit being

sufficiently vigorous to crush the threatened evils, and bring about a

healthier state of things.

The comprehensive subject of parliamentary elections is rich in

interest and entertainment; the history of the rise, progress, and

development of the complex art of electioneering recommends itself to

the attention of all who have an interest in the features inseparable

from that constitution which has been lauded as a model for other

nations to imitate. The strong national characteristics surrounding, in

bygone days, the various stages of parliamentary election--peculiarly a

British institution, in which, of all people, our countrymen were most

at home--are now, by an improved elective procedure, relegated to the

limbo of the past, while the records of electioneering exist but as

traditions in the present.

With the modifying influence of progress, and a more advanced

civilisation, the time may come when the narrative of the robustious

scenes of canvassing, polling, chairing, and election-feasting, with

their attendant incidents of all-prevailing bribery, turbulence, and

intrigue, may be regarded with incredulity as fictions of an impossible

age.

It has been endeavoured to give the salient features of the most

remarkable election contests, from the time when seats began to

be sought after until comparatively recent days. The “Spendthrift

Elections,” remarkable in the annals of parliamentary and party

warfare, are set down, with a selection from the literature, squibs,

ballads, and broadsides to which they gave rise. The illustrations

are selected from the pictorial satires produced contemporaneously

upon the most famous electoral struggles. The materials, both literary

and graphic, are abundant, but scattered; it is hoped that both

entertainment and enlightenment may be afforded to a tolerant public by

the writer’s efforts to bring these resources within the compass of a

volume.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I.

PAGE

The assembling of parliaments--Synopsis of parliamentary

history--Orders for the attendance of members--Qualifications

for the franchise: burgesses, burgage-tenures, scot and lot,

pot-wallopers, faggot-votes, splitting--Disqualifications:

alms, charity, “faggots,” “occasionality”--Election of knights

of the shire, and burgesses--Outlines of an election in the

Middle Ages--Queen Elizabeth and her faithful Commons--An

early instance of buying a seat in the Commons--Returns

vested in the municipal corporations; “Money makes the

mayor to go”--Privileges of parliament--“Knights girt with

a sword”--Inferior standing of the citizens and burgesses

sent to Parliament--Reluctance of early constituencies to

sending representatives to parliament--Paid members--Members

chosen and nominated by the “great families”--The Earl of

Essex nominating his partisans and servants--Exemption

from sending representatives to the Commons esteemed

a privilege--The growth of legislative and electoral

independence--The beginning of “contested elections”--Coercion

at elections--Lords-lieutenant calling out the train-bands for

purposes of intimidation--Early violence--_Nugæ Antiquæ_; the

election of a Harrington for Bath, 1658-9; the present of a

horse to paid members--The method of election for counties,

cities, and boroughs--Relations of representatives with their

constituents--The “wages” of members of parliament--“Extracts

from the Proceedings of Lynn Regis”--An account rendered to the

burgesses--The civil wars--Peers returned for the Commons in

the Long Parliament after the abolition of the House of Lords. 1

CHAPTER II.

Influence of administration under Charles I.--Ballad on

the Commonwealth--House of Commons: “A General Sale of

Rebellious Household Stuff”--The Parliament under the

Restoration--Pepys and Prynne on the choosing of “knights

of the shire”--Burgesses sent up at the discretion of the

sheriffs--The king’s writ--Evils attending the cessation of

wages to parliamentary representatives--Andrew Marvell’s ballad

on a venal House of Commons--The parliament waiting on the

king--Charles II. and his Commons--“Royal Resolutions,” and

disrespect for the Commons--The Earl of Rochester on Charles

II.’s parliament--Interference in elections--Independence

of legislators _versus_ paid members--The Peers as “born

legislators and councillors”--“The Pensioner Parliament”

coincident with the remission of salaries to members of the

Commons--“An Historical Poem,” by Andrew Marvell--Andrew

Marvell as a paid member; his kindly relations with his Hull

constituents--Writ for recovering arrears of parliamentary

wages--Uncertainty of calling another parliament--The

Duke of Buckingham’s intrigues with the Roundheads; his

“Litany”--Degradation of parliament--Parody of the king’s

speech--Relations of Charles II. and his Commons--Summary

of Charles II.’s parliaments--Petitioners, addressers, and

Abhorrers--The right of petitioning the throne--The Convention

Parliament--The Long Cavalier Parliament--The Pensioner

Parliament and the statute against corruption--“The Chequer

Inn”--“The Parliament House to be let”--The Habeas Corpus

Parliament--The country preparing for Charles II.’s fourth

parliament--Election ballads: “The Poll,”--Origin of the

factions of Whigs and Tories--Whig and Tory ballads--“A

Tory in a Whig’s Coat”--“A Litany from Geneva,” in answer

to “A Litany from St. Omer”--The Oxford Parliament of eight

days--“The Statesman’s Almanack”--A group of parliamentary

election ballads, 1679-80--Ballad on the Essex petitions--The

Earl of Shaftesbury’s “Protestant Association”--“A Hymn

exalting the Mobile to Loyalty”--The Buckingham ballad--Bribery

by Sir Richard “Timber” Temple--The Wiltshire ballad--“Old

Sarum”--Petitions against prerogative--The royal pretensions to

absolute monarchy--The “Tantivies,” or upholders of absolute

kingly rights over Church and State--“Plain Dealing; or, a

Dialogue between Humphrey and Roger, as they were returning

home from choosing Knights of the Shire to sit in Parliament,

1681;” “Hercules Rideing”--“A Speech without-doors, made

by a Plebeian to his Noble Friends”--Philippe de Comines

on the British Constitution--On freedom of speech--A true

Commonwealth--The excited state of parties at the summoning

of the Oxford Parliament, 1681--Ballads on the Oxford

Parliament--The impeachment of Fitz-Harris, and the proposal of

the opposition to exclude the Duke of York from the “Protestant

succession”--Squabble on privilege between the Peers and

Commons--The Oxford Parliament dismissed, after eight days, on

this pretence--“The Ghost of the Late Parliament to the New

One to meet at Oxford”--“On Parliament removing from London to

Oxford”--“On his Majesty’s dissolving the late Parliament at

Oxford”--A “Weeked” Parliament. 22

CHAPTER III.

Electioneering on the accession of James II.--A parliament

summoned by James II.--The municipal charters restored in

the nature of bribes--Lord Bath, “the Prince Elector,” and

his progress in the west--Electioneering strategies--How Sir

Edward Evelyn was unjustly cozened out of his election--The

constitution of James II.’s Parliament--Inferior persons “of no

account whatever” chosen to sit in the Commons--The question

of supplies, the royal revenue, and prerogative--Assembling

of James II.’s parliament--The corrupt returns boldly

denounced--Violence at the elections--The abdication of

James II., and the “Convention Parliament”--Accession of

the Prince of Orange--Ballad “On the Calling of a Free

Parliament, Jan. 15, 1678-9”--Ballads on William III.’s

Parliament: “The Whigs’ Address to his Majesty,” 1689; “The

Patriots,” 1700--An election under William III., for the

City of London--“The Election, a Poem,” 1701; the electors,

the Guildhall, the candidates; Court-schemers _versus_

patriotic representatives; and “the liberties of the people”

_versus_ the “surrendered Charters”--Electioneering under

Queen Anne--The High Church party--“The University Ballad;

or, the Church’s Advice to her Two Daughters, Oxford and

Cambridge,” 1705--Whigs and “Tackers”--The Nonconformity

Bill--Mother Church promises to “wipe the Whigs’ nose”--The

“case of Ashby and White,” and the dispute thereon between the

Lords and Commons--Breaches of privilege--“Jacks,” “Tacks,”

and the “Occasional Conformity Bill”--Ballad: “The Old Tack

and the New,” 1712--The Act against bribery--Past-masters

of the art of electioneering--Thomas, Marquis of Wharton;

his election feats, and genius for canvassing-Election,

1705--“Dyer’s Letters”--Reception of a High Church “Tantivy”

candidate--Discomfiture of the “Sneakers”--Lord Woodstock’s

electioneering ruse at Southampton, 1705--“For the Queen and

Church, Packington”--Dean Swift on election disturbances

in Queen Anne’s reign--Sir Richard Steele’s mishap when a

candidate for election--Steele’s parliamentary career--“The

Englishman” and “The Crisis”--Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, an

accomplished hand at electioneering--Her _ruse_ against Lord

Grimston--“Love in a Hollow Tree”--Dr. Johnson on scandals

revived at election-time--Failure of the High Church party

to bring in the Chevalier--The accession of George I., and

the Tory discomfiture--“The Whigs’ answer to the Tories”--The

Jacobite and Hanoverian factions--Ballads upon “Nancy,” “the

Chevalier,” and George of Hanover, 1716--The disaffected and

their hatred to Sir Robert Walpole--Ballad: “King James’s

Declaration”--The abortive Jacobite rising in 1715--Ballad:

“The Right and True History of Perkin”--The end of Perkin’s

attempt. 56

CHAPTER IV.

Sir Robert Walpole “chaired” on his election for Castle

Rising, 1701--“Robin’s Progress”--Walpole in Parliament--His

offices--Impeached by the Commons for corruption on the death

of George, Prince of Denmark--Returned for King’s Lynn--Firmly

established in power on the accession of George I.--“A

Tory Bill of Costs for an Election in the West, 1715”--The

Septennial Act, 1716--The elections of 1721--Walpole’s

“universal salve”--“The Election carried by Bribery and the

Devil,” 1721--Municipal corruption--Ballad: “Here’s a Minion

sent down to a Corporate Town”--The elections of 1727--“Ready

Money, the Prevailing Candidate; or, the Humours of an

Election,” 1727--“No bribery, but pockets are free”--Ballad:

“The Laws against Bribery Provision may make”--“The Kentish

Election, 1734”--“The Country Interest” _versus_ “the

Protestant Interest”--Vane and Dering _versus_ Middlesex

and Oxenden--Vane’s treat to his electors--Walpole paraded

in effigy--Hogarth’s design on the election of 1734: Sir

Robert Fagg--“The Humours of a Country Election,” 1734--The

first suggestion for Hogarth’s series of four election

prints--Plays, operas, and poems on elections--The oath

imposed upon electors--“A New-year’s Gift to the Electors of

Great Britain,” 1741--“The flood of corruption”--Walpole, as

“The Devil upon Two Sticks,” carried through the “Slough of

Despond,” 1741--“A Satire on Election Proceedings,” dedicated

to “Mayors and Corporations in general,” 1741--Walpole’s

lease of power threatened--Satirical version of Walpole’s

“Coat of Arms”--The Westminster election of 1741--Wager and

Sundon _versus_ Vernon and Edwin--A patriotic “Address to the

Independent and Worthy Electors” of Westminster, 1741--Royal

canvassers--“Scene at the Westminster Election,” 1741--Lord

Sundon calls in the grenadiers to close the poll--The

Westminster Petition, 1741--A new election--Wager and Sundon

unseated; Edwin and Percival returned--Admiral Vernon and

Porto Bello--“The Funeral of Independency,” 1741--“The Triumph

of Justice,” 1741--Walpole defeated--“The Banner of Liberty

displayed,” 1741--A ministerial mortification--Ballads upon

the Westminster election of 1741--“The Independent Westminster

Electors’ Toast”--“The Downfall of Sundon and Wager”--“The

Independent Westminster Choice”--“The True English-Boys’

Song to Vernon’s Glory”--Triumph of the “Country party” or

“Patriots”--“The Body of Independent Electors of Westminster”

constituted into a society--Their anniversary dinners--A

dinner-ticket, 1744--The Stuart rising of 1745--Lord

Lovat’s trial--Meeting of “The Independent Electors of the

City and Liberty of Westminster” at Vintners’ Hall, March,

1747--Jacobite toasts--“The Spy detected:” ejectment of a

ministerial spy from Vintners’ Hall--The state of parties

at the Westminster election, 1747--Earl Gower and his son,

Lord Trentham--Falling-off of the Independent party--Trentham

and Warren _versus_ Clarges and Dyke--“The Two-Shilling

Butcher,” 1747--The Duke of Cumberland and the Prince of Wales

as rival canvassers--The Duke of Bedford’s support of Lord

Trentham--“The Jaco-Independo-Rebello-Plaido”--“The Humours of

the Westminster Election; or, the Scald Miserable Independent

Electors in the Suds,” 1747--Jacobite vagaries--“Great

Britain’s Union; or, the Litchfield Races,” 1747--The

Jacobite rebellion--Political animosities carried on to the

race-course--Alternate Whig and Tory race meetings--The Duke

of Bedford horsewhipped at the Litchfield races on Whittington

Heath--Ballad on the _fracas_: “The Lords’ Lamentation; or,

the Whittington Defeat,” 1747--Trentham _versus_ Vandeput,

1749--The _fracas_ at the Haymarket Theatre--Frenchified Lord

Trentham’s deadly attack on his own electors--Gallic valour

and the Admiralty Board--Ballad: “Peg Trim Tram in the Suds;

or, No French Strollers,” 1749--“Britannia Disturbed, or an

Invasion by French Vagrants, addressed to the Worthy Electors

of the City of Westminster,” 1749--Violence and bribery--“Aux

Electeurs très dignes de Westminster”--The Duke of Bedford’s

oppression and injustice to his tenants--Hogarth’s print of “A

Country Inn-yard at the Time of an Election,” 1747--The Hon.

John Child--“No Old Baby.” 78

CHAPTER V.

The Pelham Administration--Corruption rife--“The Duke of

Newcastle as the Complete Vermin-Catcher of Great Britain;

or, the Old Trap new baited,” 1754--Ministerial bribes

and baits--Boroughmongering--“Dissection of a Dead Member

(of Parliament)”--A mass of corruption--Henry Pelham’s

measures--The Jews’ Naturalization Bill, 1753--Death of

Pelham--“His Arrival at his Country Retirement and Reception,”

1754--Pelham’s reception across the Styx--The elections of

1754--Humours of canvassing--The election for the City of

London: “The Liveryman’s Levee,” 1754--“The City Up and Down;

or, the Candidates Pois’d,” 1754--City candidates: Sir John

Barnard, Slingsby Bethell, William Beckford, Sir Richard Glyn,

Sir Robert Ladbroke, Sir Crispe Gascoyne, and Sir William

Calvert--Sir Sampson Gideon, the loan contractor, and “The

Jews’ Naturalization Bill”--“A Stir in the City; or, Some

Folks at Guildhall,” 1754--Ballad on the City election at the

Guildhall--“The Parliamentary Race; or, the City Jockies,”

1754--Ballad on “The Parliamentary Race for the City”--The

London and Oxfordshire elections--“All the World in a Hurry;

or, the Road from London to Oxford,” 1754--Ballad on “The

London Election”--The Oxford Election; Candidates: Wenham and

Dashwood _versus_ Turner and Parker--Ballad on the Oxford

election--The four election pictures by William Hogarth

having reference to the county election for Oxfordshire,

1754--“The Election Entertainment”--Humours of an election

feast--“The low habits of venal wretches”--“The New Interest”

_versus_ “The Old Interest”--Election party cries in 1754:

“Give us our eleven days”--Ballad on alteration in the

style--Party animosities--“Act against Bribery”--“Kirton’s

Best”--“Canvassing for Votes,” 1754--“Punch, Candidate for

Guzzledown”--“The Royal Oak” _versus_ “The Crown,” otherwise

“The Excise Office”--“The Polling Booth,” Oxfordshire,

1754--Ballad on the humours of polling--“Chairing the Members,”

1754--Burlesque on Bubb Dodington--The dangers of chairing--A

ministerial dinner, 1754--Hogarth’s sketches of “Bubb

Dodington and the Earl of Winchilsea”--Murderous incidents

of the Oxfordshire election--Wrecking houses--Parliamentary

interest _versus_ place--Hawking “marketable ware”--Diary

of Bubb Dodington (Lord Melcombe Regis)--Overtures from

the Pelhams--Bubb’s “parliamentary interest”--A prime

minister--“Bubbling” a boroughmonger--The intriguer

over-matched--The Bridgwater Election, 1754--Details of an

election contest in 1754, from Dodington’s diary--The Duke of

Newcastle, an arch-negotiator--Bubb and his “parliamentary

interest” bought for nothing--The vitiating effects of bribery

and corruption on a representative legislature--“Burning

a Prime Minister in Effigy,” 1756--Denunciations against

venal ministers and the vital injuries they inflict on the

constitution. 125

CHAPTER VI.

John Wilkes, the _pseudo_ “Champion of Liberty”--W.

Hogarth as a partisan--His attack on Wilkes and Churchill,

the _North Briton_, 45--Hogarth’s unfortunate political

satires--“The Times,” Plate I., 1762--Lord Bute as Hogarth’s

patron--“The Epistle to Hogarth,” by Churchill--“The

Times,” Plate II., withheld from publication; given to

the public in 1790--The demagogue tried in court at

Westminster--Hogarth’s print of “John Wilkes, a patriot”--The

_North Briton_, No. 45--Severe animadversions on Hogarth by

Wilkes and Churchill--The “Bruiser,” Charles Churchill, by

Hogarth--His reprisal--Hogarth, Wilkes, and Churchill: “A

Bear Leader”--Wilkes’s illegal imprisonment on “a general

warrant”--Wilkes in the Tower--“A Safe Place,” 1763--“Daniel

cast into the Den of Lions; or, True Blue will never stain,”

1763--Wilkes set at liberty--His appearance in parliament,

and duel--Wilkes absconds to Paris--Is outlawed for contempt

of court--Returns from Paris, and contests the City of London

at the general election, 1768--The City candidates--The

nomination--The poll--Wilkes at the bottom of the poll--The

adulation of the mob--Wilkes’s letter to the king--His

submission to the Treasury--Wilkes a candidate for the

county of Middlesex--“The Return of Liberty,” and “Liberty

revived”--The Brentford election--Violent conduct of the

“Wilkes and Liberty” mob--Candidates for Middlesex--“No.

45 N.B.”--Wilkes returned for Middlesex--Dr. Franklin on

“Wilkes and the Brentford election”--“John Wilkes elected

Knight of the Shire for Middlesex, March 28, 1768, by the

Free Voice of the People”--More of the “Wilkes and Liberty”

riots--The mob in London--Universal turbulence--The attack on

the Mansion House--“The Laird of the Boot”--“The Rape of the

Petticoat”--Lord Bute and the Princess of Wales--The _Oxford

Magazine_ on the valour of the Lord Mayor--The view taken by

the _Political Register_--Ballad on Lord Mayor Harley’s seizure

of the “Boot and Petticoat”--Surrender of Wilkes--Released

by the rabble--His second surrender--“The Scot’s Triumph; or,

a Peep behind the Curtain”--Wilkes a prisoner in the King’s

Bench--The Wilkes riots in St. George’s Fields--Southwark in

a state of siege--The military under arms--Wilkes’s address

from the King’s Bench Prison, “To the Gentlemen, Clergy, and

Freeholders of the County of Middlesex”--The mob demonstration

outside the King’s Bench on the opening of parliament--The

Riot Act read--The massacre of St. George’s Fields--The case

of William Allen, deliberately assassinated--“The Scotch

Victory; murder of Allen by a Grenadier.--St. George’s Fields,

1768”--The ministerial approval of the butcheries by the

soldiers--Justice Gillam--The circumstances of the riot--The

soldiers tried--The murderer shielded from justice; his escape,

and subsequent pension--Horne Tooke as a witness--He brings

the guilty to justice--The defence by the Government--“The

Operation,” 1768--“Murder screened and rewarded” 157

CHAPTER VII.

Death of Cooke, Tory member for Middlesex, 1768--A fresh

election--Serjeant Glynn, Wilkes’s advocate, a Radical

candidate for the vacant seat; opposed by Sir W. Beauchamp

Proctor--Proctor’s mob of hired ruffians--“The Hustings

at Brentford, Middlesex Election”, 1768--Prize-fighters

employed to terrorize the electors--Dastardly attack

on the hustings--Glynn’s “Letter to the Freeholders of

Middlesex”--Proctor’s repudiation of the charge of “hiring

banditti”--Horne Tooke’s “Philippic” to Proctor--The true

facts of the case--The circumstantial account given in the

_Oxford Magazine_--The rioters beaten off--Electioneering

manœuvres: summoning electors as jurymen--The bruisers

recognized--Broughton engaged as generalissimo of the

forces--An expensive contest--Glynn’s letter of acknowledgment

to his constituents--The “Parson of Brentford”--Poetical

tributes to Horne Tooke--Results of the injuries inflicted

by the hired ruffians: Death of Clarke--“The Present State

of Surgery; or, Modern Practice,” 1769--Trial of Clarke’s

murderers--The bruisers defended by the ministers--Found

guilty, and sentenced to transportation, but receive a royal

pardon and pensions for life--Partial conduct and verdict of

the College of Surgeons--“A Consultation of Surgeons”--The

petitions and remonstrances addressed to the Throne--Colonel

Luttrell sent to parliament, though not duly elected, to

represent Middlesex in place of Wilkes--An unconstitutional

vote of the Commons: “296 votes preferred to 1143”--Lord

Bacon on the lawful power of Parliaments--The Crown and its

advisers, and the odium attaching to their unconstitutional

proceedings--Servile addresses--The loyal address from the

“Essex Calves”--“The Essex Procession from Chelmsford to St.

James’s Market for the Good of the Common-Veal,” 1769--Charles

Dingley, “the projector”--The bogus city address--“The

Addressers”--The _fracas_ at the King’s Arms, Cornhill--A

battle-royal--“The Battle of Cornhill,” 1769--Administrative

bribes of preference “Lottery Tickets”--“The Inchanted

Castle; or, King’s Arms in an Uproar,” 1769--Walpole’s

account of the procession--“The Principal Merchants and

Traders assembled at the Merchant Seamen’s Office to sign

y^e Address”--“Epistle to the _North Briton_,” 1769--The

“Abhorrers” of Charles II.’s reign revived--The Administration

arraigned with their crimes--Address of the Quakers to James

II.--“The conduct of ninety-nine in a hundred of the people

of England ‘Abhorred’”--The loyal address forwarded to St.

James’s Palace--“The Battle of Temple Bar,”--The addressers

routed--“Sequel to the Battle of Temple Bar: Presentation of

the Loyal Address at St. James’s Palace,” 1769--The fight

at Palace Yard--“The Hearse,” and Lord Mountmorres--The

lost Address recovered--Account of the procession from the

_Political Register_--The _Town and Country Magazine_--A royal

proclamation against the rioters: _Gazette Extraordinary_--“The

Gotham Addressers: or, a Peep at the Hearse”--“A Dialogue

between the Two Heads on Temple Bar,” 1769 178

CHAPTER VIII.

More petitions and remonstrances to the king--Petition

of the Livery of London--The king’s advisers denounced

by the citizens--An arraignment of ministerial crimes

and misdemeanours--Undue prerogative and its abuses--The

alienation of our colonies, and the consequent loss of

America--The king’s contemptuous reception of the city

petition--Disrespect shown to the corporation at the Court

of St. James’s--Threatening attitude of the military--An

unscrupulous and tyrannical ministry--A poetical petition--The

king visits the city petition with “severe censure”--A more

stringent remonstrance prepared--The violated “right of

election”--An unrepresentative parliament--“The true spirit

of parliaments”--“The constitution depraved”--The Coronation

Oath violated--The king’s answer, condemning the former

petition, and the city remonstrance--“Nero fiddled while

Rome was burning”--Further popular agitations--Horne Tooke’s

“Address to the Freeholders of the county of Middlesex”--“The

Middlesex Address, Remonstrance and Petition”--“Constitutional

liberties attacked in the most vital part”--“A self-elected

and irresponsible Parliament”--The petitions from Middlesex

and Kent received at St. James’s in silence--The Westminster

remonstrance--Corrupt administration of the House of

Commons--The king prayed to dissolve a parliament no longer

representing the people--The right of petitioning impeached

by the Commons--The king replies that “he will lay the

remonstrance before parliament”--“Making a man judge in his

own trial”--The undignified reception of the Westminster

remonstrance--Parliamentary counter-petitions at the

bidding of corrupt ministers--The city vote of thanks to

Lord Chatham, for his patriotic “zeal for the rights of the

people”--The king’s answer considered at a general assembly

of the citizens--Alderman Wilkes on the violation of the

rights of election and of the constitution--The recorder

characterises the remonstrance as a libel--The conduct of

ministers in the case of Colonel Luttrell’s election--A fuller

remonstrance from the city--The results of the Revolution of

1788 contravened--The king’s answer--Beckford requests leave

to reply--His dignified speech to the king--The king remains

silent--“Nero did _not_ fiddle while Rome was burning”--The

courtiers abashed--The king prorogues parliament with an

address approving of the conduct of both Houses--The citizens

eventually triumph in “the cause of Liberty and of the

Constitution”--Lord Chatham’s eulogium pronounced upon the

“patriotic spirit of the metropolis”--Beckford and Chatham,

the champions of popular rights--The national importance of

their conduct at this crisis of our history--Civic honours

paid to Beckford--His speech to the king inscribed on the

monument erected to his memory in the Guildhall--The corrupt

ministers cowed--An uncontested election for Westminster,

1770--Sir Robert Bernard’s nomination--His election, without

expense or disorder--Speeches of Sir J. Hussey Delaval and

Earl Mountmorres on the late conduct of the Government--The

advantages of leaving the people to the legitimate exercise of

their liberties, uninfluenced by the administrative interest,

corruption, and undue influence, the usual features at an

election. 207

CHAPTER IX.

“The Spendthrift Election,” Northampton, 1768--Expensive

contests, the defeated men appearing in the

_Gazette_--Colchester; Hampshire--Three noble patrons

adversaries at Northampton: the Earls of Halifax,

Northampton, and Spencer--Open-house at ancestral seats--The

“perdition of Horton”--The petition and scrutiny on the

Northampton election--The event referred to chance--Cost

of the contest--The results of the reckless expenditure

upon the fortunes of the patrons--Sir Francis Delaval at

Andover, 1768--His attorney’s bill: item, “to being Thrown

out of window, £500”--Reckoning without the host--An

hospitable entertainment--Returning thanks--The Mayor

_versus_ the Colonel--“Sir Jeffery Dunstan’s Address to

the Electors of Garratt,” 1774: a parody upon election

manifestoes-“Lord Shiner’s Appeal to the Electors of

Garratt”--Bribery at elections, and “controverted election

petitions”--Various methods of acquiring “Parliamentary

interest”--Boroughs cultivated for the market, like

other saleable commodities--Patronage--Buying up

burgage-tenures--Recognized prices of votes--The Ilchester

tariff--“Dispensers of seats”--Lord Chesterfield’s experience

of borough-jobbing--The seven electors of Old Sarum--Typical

sinks of corruption--Boroughbridge, Yorkshire--“The last

of the Boroughbridges”--A solitary franchise-holder; one

man returning two representatives--The bribery scrutiny,

Hindon, 1774--203 bribed electors out of a constituency of

210--Wholesale corruption--Bribing candidates committed to the

King’s Bench--A fine of “a thousand marks”--Boroughmongering

at Milborne Port--Lord North’s agent--A wholesale purchase

of “bailiwicks”--Supineness of the Commons and ministerial

influence--Corrupt bargains ignored by the House--Illegal

interference of peers and lords of parliament in elections;

Westminster election, 1774--“Money, meat, drink, entertainment

or provision”--The partiality of persons in power manifested

at “election bribery commissions”--The “king’s menial servants

disqualified”--“Direct solicitation of the peers”--Worcester,

1774, wholesale swearing-in of electors as special

constables--Convenient formula for defeating evidence of

bribery before the House--High-Sheriffs returning themselves,

Abingdon, 1774--The instance of Sir Edward Coke--“The sheriff

in no respect the returning officer for boroughs”--The

election made void by the sheriff returning himself--Morpeth,

1774--An election determined by main force--The candidate

forcibly returning “himself and friend”--A “bribing” candidate

preferred to a “main-force” candidate--Petersfield, Hants--The

Shaftesbury “Punch,”--Pantomimic method of distributing

bribes--The mysterious “Glenbucket”--Sudbury, 1780--A wager on

the result of a controverted petition--A mayor insisting upon

carrying on an election all night--The Shaftesbury “Punch”

outdone by the Shoreham “Christian Society”--A well-organized

scheme for “burgessing business”--The “Society” a “heap of

bribery”--Stafford, 1780; The price paid by R. B. Sheridan

for his seat--Tom Sheridan a candidate for Stafford, on his

father’s retirement, 1806--The successful candidate for

Stafford presented with a new hat at the hustings, by a

subscription of his constituents--“A Mob-Reformer,” 1780--The

first entry into public life of William Pitt--“The spirit of

the country in 1780”--Pitt seated for Appleby, one of Sir James

Lowther’s pocket-boroughs--Pitt’s early political friends:

the Duke of Rutland and Lord Euston--Pitt’s letter to his

mother, Lady Chatham, on his coming election--No necessity to

visit constituencies--Choice of seats offered to the young

premier, 1784--Nominated for the City of London--Invited

to stand for Bath, represented by his late father Earl

Chatham--Pitt returned for the University of Cambridge,

1784, which he represented till his death--The dissolution

delayed by the theft of the Great Seal from the Chancellor’s

residence, 1784--Pitt’s letter to Wilberforce on the coming

elections--Pitt “a hardened electioneerer”--The war carried

into the great Whig strongholds--The subscription to forward

Wilberforce’s return for Yorkshire--Earl Stanhope on “Fox’s

Martyrs”--Fox’s courage under adversity--Wilkes returned as the

ministerial representative for Middlesex--Wilkes’s “address

to the electors”--“The Back-stairs Scoured”--“The boldest

of bilks”--“Reconciliation of the Two Kings of Brentford,”

1784--“The New Coalition,” 1784--Charles James Fox’s first

entry into public life--Returned for Midhurst, 1769--His first

speech on the Wilkes case--Wilkes at a levée: he denounces to

the king his friend Glynn as a “Wilkite”--Canvass of Pitt’s

friends--The poet Cowper’s description of Pitt’s cousin, the

Hon. W. W. Grenville, seeking for suffrages--The amenities of

canvassing in the old days: saluting the ladies and maids--A

most loving, kissing, kind-hearted gentleman--W. W. Grenville

and John Aubrey returned for Buckinghamshire, 1784 226

CHAPTER X.

The Great Westminster election of 1784--Wilkes’s famous

election contest for Middlesex dwarfed by comparison-State

of political excitement--Relations of parties in the

Commons--Fox’s India Bill--“Carlo Khan”--Downfall of the

Coalition Ministry--Pitt made premier by the will of the

king--“Back-stair influence,” and Court intrigues--“The

royal finger”--Hostility of the East India Company against

Fox--An administration called to power with a working

minority--Defeated on division--Vote of want of confidence--The

House dissolved--The great election campaign--“The storm

conjured up”--The popular aversion to the late Coalition

Ministers shown at the hustings--“The royal prerogative exerted

against the palladium of the people”--Horace Walpole on the

situation--The Whig losses all over England--Fox’s contest for

Westminster--A forty days’ poll--The metropolis in a state of

ebullition--Party cries--The streets a scene of combat--The

rival mobs--The Guards--Hood’s sailors; their violent

partisanship and reckless attacks--The “honest mob”--Fox’s

narrow escape--The Irish chairmen beat the sailor-mob--A

series of pitched battles--Partial behaviour of the special

constables--Their interference and violence--Flood of ballads

and political squibs--Rowlandson’s caricatures on the

contest--The odium revived against the late Coalition Ministry;

turned to political account by the Court party--“The Coalition

Wedding: the Fox and the Badger quarter their Arms”--“Britannia

aroused; or, the Coalition Monsters destroyed”--Pitt’s election

manœuvres; his bidding for the favour of the citizens--Pitt

presented with the freedom of the city--“Master Billy’s

Procession to Grocers’ Hall”--The king threatens to retire

to Hanover in the event of a defeat--Ministerial wiles--Bids

of place and pension--Extensive “ratting”--“The Apostate

Jack Robinson, the Political Rat-catcher. N.B. Rats taken

alive!”--“The Rival Candidates: Fox, Hood, and Wray”--Rival

canvassers--“Honest Sam House, the Patriotic publican”--The

hustings, Covent Garden--The “prerogative standard”--“Major

Cartwright, the Drum-Major of Sedition”--“The Hanoverian

Horse and the British Lion”--“Fox, the Incurable”--Fair

canvassers--The ladies of the Whig aristocracy a bevy of

beauty; the Duchess of Devonshire, the Countess of Duncannon,

the Duchess of Portland, Lady Carlisle, etc.--“The Devonshire,

or Most Approved Manner of securing Votes”--“A Kiss for a

Vote”--Tory lady canvassers: Lady Salisbury, the Hon. Mrs.

Hobart--“Madame Blubber, the Ærostatic Dilly”--Walpole’s

account of the canvassing--Fox’s favour with the fair--The

Duchess of Devonshire’s exertions on behalf of the Whig

chief--Earl Stanhope on “Fox’s Martyrs”--His account of

the contested election--Pitt’s letters on the Westminster

election, to Wilberforce, and James Grenville--Pitt’s account

of the country elections--His anxiety about Westminster--Earl

Stanhope’s summary of the Westminster election--Ballads on

the contest--“The Duchess Acquitted; or, the True Cause of

the Majority on the Westminster Election”--Tory libels on the

Duchess of Devonshire--“The Wit’s Last Stake; or, the Cobbling

Voters and Abject Canvassers”--“The Poll”--Animadversions

against Sir Cecil Wray--“Lords of the Bedchamber”--“The

Westminster Watchman”--A flood of _jeux d’esprit_--“On undue

influence”--“A concise Description of Covent Garden at the

Westminster election”--“Stanzas in Season”--The Prince of Wales

a zealous partisan of Fox--“Lady Beauchamp, Lady Carlisle, and

Lady Derby at the Hustings”--Poetical tributes--The Duchess

of Devonshire saves the Whig cause at Westminster--“On the

Duchess of Devonshire and Lady Duncannon canvassing for

Fox”--“On a certain Duchess”--Horace Walpole’s nieces, the

Ladies Waldegrave, “the three Sister Graces,” canvassing

for Fox--“Epigram on the Duchess of Devonshire”--“Impromptu

on her Grace of Devon”--“Ode to the Duchess”--“The Paradox

of the Times”--A new Song, “Fox and Freedom”--The downfall

of Wray--“The Case is Altered”--Bringing in outlying

voters--“Procession to the Hustings after a Successful

Canvass”--“Every Man has his Hobby-Horse”--Fox carried into the

House by the duchess--_Exit_ Sir Cecil Wray!--“For the Benefit

of the Champion--a Catch.” “No Renegado!” Wray defeated--“The

Westminster Deserter drumm’d out of the Regiment”--Apotheosis

of the fair champion--“Liberty and Fame introducing Female

Patriotism (the Duchess of Devonshire) to Britannia”--The

close of the poll--Wray demands a scrutiny--Partial and

illegal conduct of the high bailiff as returning-officer--Fox

triumphant--The ovation--The chairing procession--Two days

of festivities--The reception at Devonshire House--The

Prince of Wales’s rejoicings--The fête at Carlton

Palace--Rival interests--Mrs. Crewe’s rout--The tedious and

prolonged progress of the scrutiny--Fox for Kirkwall--“The

Departure”--Fox recovers damages against the high bailiff

for illegality in refusing to make a return--The affair only

settled a year later--“Defeat of the High and Mighty Balissimo

Corbettino and his Famed Cecilian Forces, on the Plains of

St. Martin,” 1785--Corbett ordered by the court to make his

return--Cast in damages--Fox’s final majority 257

CHAPTER XI.

Another Westminster election, 1788--Lord Hood appointed

to the Admiralty Board, 1788--A fresh contest--Lord John

Townshend, a candidate in the Whig interest--Defeat of Lord

Hood--Two Whig members for Westminster--Mob violence, the

Guards, Hood’s sailors--Ministerial support--“Election Troops

bringing their Accounts to the Pay-table” (Treasury Gate),

1788, by J. Gillray--“An Independent Elector”--Helston,

Cornwall, 1790--Lady canvassers--A violent “eccentric”--“Proof

of the Refined Feelings of an Amiable Character, lately a

Candidate for a Certain Ancient City,” by J. Gillray--“The

‘Marplot’ of his Own Party”--Abuses of patronage--Traditions

of boroughmongering--Accumulations of seats and parliamentary

interests--Cartwright’s tables of pocket boroughs--Pitt’s early

patron, Sir James Lowther--“The tyrant of the North”--“Pacific

Entrance of Earl Wolf (Lord Lonsdale) into Blackhaven,”

1792--Great distress prevalent throughout the country, in

1795; its effect on political agitation--Political clubs

clamour for parliamentary reform--The king and his advisers

in disfavour--Revolutionary societies and the “Seditions

Bill”--Gillray’s caricatures--“Meetings of Political Citizens

at Copenhagen House,” 1795--Whig agitation against the

threatened incursions on the “liberty of the subject”--“The

Majesty of the People”--“A Hackney Meeting,” 1796--A threatened

constitutional struggle averted by a dissolution of parliament,

1796--Pitt’s tactics--“The Dissolution; or, the State Alchymist

producing an Ætherial Representation,” 1796--Mr. Hull’s

costly electioneering experience at Maidstone, 1796--Horne

Tooke unsuccessful at Westminster, 1790 and 1796--Fox and

the favour of the mobocracy--“The Hustings, Covent Garden,”

1796--Electioneering squibs--The _Anti-Jacobin_ and the

member for Southwark--Canning’s lines on George Tierney,

“The Friend of Humanity and the Knife-grinder,” 1797--Grey’s

reform measure first moved in 1797--Defeat of the Whigs,

and their temporary abstention from the debates--Increased

political agitation out of doors--Great reform meetings--Medal

commemorative of the gathering at Warwick--“Loyal Medal,” a

parody of the “Greathead” patriotic medal--The secession of

“the party”--Horne Tooke as a political agitator--The Brentford

Parson’s pamphlets--Horne Tooke a political portrait painter,

and the _Anti-Jacobin_--“Two Pair of Portraits, dedicated to

the Unbiased Electors of Great Britain,” 1798--Meeting on the

twentieth anniversary of Fox’s membership for Westminster--The

Whig chief’s speech to his constituents--“The Worn-out Patriot;

or, the Last Dying-Speech of the Westminster Representative

at the Shakespeare Tavern,” 1800--Horne Tooke seated for “Old

Sarum”--The opposition to his membership led by Temple--Lord

Camelford’s nominees--“Political Amusements for Young

Gentlemen; or, the Brentford Shuttlecock,” 1801--“Horne Tooke

as the ‘Shuttlecock’”--Unexpected honours thrust upon Captain

Barlow at Coventry, 1802--Middlesex Election for 1804--The

Brentford Hustings--“A Long Pull, a Strong Pull, and a Pull

All Together;” Sir Francis Burdett drawn to the poll--“The

Governor in his Glory,” 1804--The Westminster election,

1806--The Radical Reformers--“Triumphal Procession of Little

Paull”--“The Highflying Candidate mounting from a Blanket,”

1806--The coalition between Hood and Sheridan--Paull tossed

at the hustings--Burdett for Middlesex--“Posting to the

Election; or, a Scene on the Road to Brentford,” 1806--William

Cobbett “A Radical Drummer,” 1806--“Coalition Candidates,”

Hood and Sheridan--Sheridan disconcerted--“View of the

Hustings in Covent Garden, Westminster Election,” 1806--“Who

suffers?”--The general election, 1807--A split in the Radical

camp--Differences between Burdett and Paull--“Patriots deciding

a Point of Honour; or, the Exact representation of the

Celebrated Rencontre which took place at Coombe Wood, between

Little Paull the Tailor and Sir Francis Goose,” 1807--“The Poll

of the Westminster Election,” 1807--“the Republican Goose at

the Top, etc.”--Horne Tooke and Sir Francis Burdett--“The Head

of the Poll; or, the Wimbledon Showman,” 1807--“The Chelmsford

Petition; Patriots addressing the Essex Calves” 289

CHAPTER XII.

The “royal” Duke of Norfolk an enthusiastic

“electioneerer”--Wilberforce’s electioneering experiences--His

contest for Hull--The price of freemen--The great fight for

Yorkshire, 1807--“The Austerlitz of Electioneering”--The

candidates, Wilberforce, Lord Milton and Lascelles--The

Fitzwilliam and Harewood interests--Three hundred thousand

pounds expended--The voluntary subscription to defray the

expenses of Wilberforce’s candidature--The poll--The county

in a state of ferment--Election wiles; false rumours;

“Bruisers”--All the conveyances bespoke--Wilberforce’s

victory--His motives for the contest--“Groans of the

Talents”--Personation--Female canvassers under false

colours--Travelling expenses of electors--Carrying cargoes

of freeholders by water--Kidnapping--The caricaturists on

elections--Customary episodes of a Westminster election,

delineated by Rowlandson and Pugin--George Cruikshank as

an election caricaturist--The “Speaker’s Warrant” for

committing Burdett to the Tower, 1810--“The Little Man in

the Big Wig,” 1810--“The Election Hunter,” 1812--“Saddle

White Surrey for Cheapside”--Southwark election, 1812--“The

Borough Candidates”--“An Election Ball,” 1813--The Westminster

election, 1818--“The Freedom of Election: or, Hunt-ing

for Popularity and Plumpers for Maxwell,” 1818--“Hunt, a

Radical Reformer”--“A Political Squib on the Westminster

Election,” 1819--“Patriot Allegory, Anarchical Fable, and

Licentious Parody”--Major Cartwright, an unsuccessful

candidate--Cartwright’s Petition to the House of Commons

on the needful reform of a corrupt representative

system, 1820--Statistics of borough-mongering--“Sinks

of corruption”--“353 members corruptly imposed on the

Commons”--The coming elections of 1820--John Cam Hobhouse--His

imprisonment--“Little Hob in the Well”--“A Trifling

Mistake--corrected,” 1820--Radicals--“The Root of the King’s

Evil; Lay the Axe to it,” 1820--The Riot Act--“The Law’s Delay.

Showing the advantage and comfort of waiting the specified time

after reading the Riot Act to a Radical Mob; or, a British

Magistrate in the Discharge of his Duties, and the People

of England in the Discharge of Theirs,” 1820--“The Election

Day”--Dissolution of Parliament, 1820--“Coriolanus addressing

the Plebs,” 1820--“Freedom and Purity of Election! Showing the

Necessity of Reform in the Close Boroughs,” 1820--“Radical

Quacks giving a new Constitution to John Bull,” 1820--Burdett

and Hobhouse as Radical Reformers 324

CHAPTER XIII.

The last parliament of George IV.’s reign--The country

clamorous for retrenchment--The Tory _régime_ growing

irksome--The king’s illness, 1830--John Doyle’s caricatures

upon public events (HB’s “political sketches”)--“Present

State of Public Feeling Partially Illustrated,”

1830--Death of the king--“The Mourning Journal: Alas! Poor

Yorick!”--“The Magic Mirror; or, a Peep into Futurity”--The

Princess Victoria--Accession of William IV.--Whig

prospects reviving--Brougham, “A Gheber worshipping the

Rising Sun”--Wellington, a “Detected Trespasser”--Party

intrigues--“Anticipation; or, Queen Sarah’s Visit to

Bushy”--The old campaigner--“_Un_-Holy Alliance; or, an

Ominous Conjunction”--The general election, 1830--“Election

Squibs and Crackers for 1830. Before and After the

Election”--Caricaturists, as politicians, usually above party

prejudices--W. Cobbett returned for Oldham--“Peter Porcupine”

an M.P.--“A Characteristic Dialogue”--Changes of seats--“The

Noodle Bazaar”--Heads for Cabinets--John Bull and the

_Times_--“The man that is easily led by the nose”--“Resignation

and Fortitude; or, the Gold Stick”--“The Rival Candidates;”

Boai and Grant--Wellington’s leadership threatened: “The

Unsuccessful Appeal”--The popular will--Attacks upon the

Wellington and Peel Ministry--Results of the general election

unfavourable to the Cabinet--“A Masked Battery”--“A Cabinet

Picture”--“Guy Fawkes; or, the Anniversary of the Popish

Plot”--Defeat foreshadowed--“False Alarm; or, Much Ado

about Nothing”--The Eastern Question fatal to Wellington’s

Ministry--“Scene from the Suppressed Tragedy entitled the

Turco-Greek Conspiracy”--“His Honour the Beadle (William IV.)

driving the Wagabonds out of the Parish”--The adoption of

liberal progress--Preliminary skirmishing--“The Coquet”--The

ministry thrown out--“Examples of the Laconic Style”--“A

very Prophetical and Pathetical Allegory,” 1831--Reform on

the road--“Leap-Frog down Constitution Hill,” 1831--Another

appeal to the country--“Anticipated Radical Meeting”--The

dissolution--“Great Reform” Specialists; John Bull and his

constitutional deformity--“Hoo-Loo-Choo, _alias_ John Bull,

and the Doctors”--“May-Day”--“Leap-Frog on a Level; or,

Going Headlong to the Devil”--The Reformers having it all

their own way--A swinging pace--Political squibs on the

elections of 1831--The great battle of Lord Grey’s Reform

Bill--“The New Chevy Chase,” a poetical version of the reform

struggle--“Votaries at the Altar of Discord”--“Peerless

Eloquence”--Slaughter of the Innocents--“Niobe

Family”--Extinction of pocket boroughs--Reform at a breakneck

pace--“John Gilpin”--William IV. carried away by the old

Grey--“The Handwriting on the Wall: ‘Reform Bill!’”--A warning

to reformers--Grey and “Brissot’s Ghost”--“Macbeth” and “The

Tricoloured Witches”--Grey, Durham, and Brougham--Althorp and

Russell--A tub to a whale--“A Tale of a Tub, and the Moral

of the Tail”--Renovations at the King’s Head: “Varnishing--A

Sign (of the Times)”--“The Rival Mount-o’-_Bankes_; or, the

Dorsetshire Juggler”--Root-and-branch reform--“LINEal Descent

of the Crown,” a hint from Hogarth’s works, 1832--Hobhouse in

office--“The Cast-off Cloak”--Radicalism over-warm--“Mazeppa”

(William IV.): “Again he urges on his wild career”--“Ministers

in their Cups” 343

CHAPTER XIV.

John Doyle, a Tory Caricaturist--The Tories out in the

cold--“The Waits,” 1833--Grey and the king--“Sindbad the

Sailor and the Old Man of the Sea,” 1833--Parliamentary

reform not carried far enough--Burdett, Hume, and O’Connell:

“Three Great Pillars of Government; or, a Walk from White

Conduit House to St. Stephen’s,” 1834--“Time running away

with the Reform Bill”--General election, 1834-5--Party

competition--“The Opposition ’Busses”--“Original Design

for the King’s Arms, to be placed over the New Speaker’s

Chair,” supporters, Burdett and Cobbett--“Inconveniences that

might have arisen from the Ballot”--Bribery and violence

discounted--General election of 1835--Broadside squibs on the

Windsor election--Tory view of the decline of the British

constitution, “A New Instance of the Mute--ability of Human

Affairs,” 1837--Appeal to the Constituencies in 1837--“Going

to the Fair with It: a cant phrase for doing anything in an

extravagant way”--Contortions of statesmen to keep in place:

“Ins and Outs”--“Fancy Ball: Jim Crow Dance and Chorus,”

1837--Conversion of Sir Francis Burdett from Radicalism to

Toryism--“A Fine Old English Gentleman, one of Olden Time,”

1837--A bye-election for Westminster--Burdett opposed by

Leader--“Following the Leader”--“May-Day in 1837”--Whig

gambols--Sir Francis Burdett invites the verdict of his

Westminster constituents upon his change of front--Thackeray’s

pictorial squib on the event--“The Guide”--“The Rivals; or,

Old Tory Glory and Young Liberal Glory,” 1837--Sir Francis

Burdett re-elected--His valedictory speech at the Westminster

hustings, 1837--His quarrel with Daniel O’Connell, the

Liberator--Defeat of Leader--“The Dog and the Shadow”--“Race

for the Westminster Stakes between an Old Thoro’bred and a

Young Cock-tail; weight for age. The old ’un winning in a

canter,” May, 1837--“Taking up a Fare: All the World’s a

Stage”--Burdett’s attack on Democracy--“The Last and Highest

Point at which the unheard-of Courage of Don Quixote ever did,

or could arrive, with the Happy Conclusion”--“An Old Song to

a New Tune”--“The Raddies”--Fate of Leader--“A Dead-horse:

a sorry subject; what was once a Leader in the Bridgwater

Coach”--“The Three Tailors of Tooley Street. We, the People

of England”--“Reorganizing the (Spanish) Legion”--Burdett

for North Wilts--“Grinding Young”--Lord Durham--“The Newest

Universal Medicine”--“The Rejected of Kilmarnock”--Joseph Hume

defeated at Middlesex--“Figurative Representation of the Late

Catastrophe!”--Dan O’Connell providing the rejected candidates

with seats--“Great Western General Booking Office”--Hume for

Kilkenny--“Shooting Rubbish”--The interval before parliament

reassembled--“Retzsch’s Extraordinary Design of Satan Playing

at Chess with Man for his Soul,” 1837--Party tactics--“A Game

at Chess (again): the Queen in Danger”--“High Life below

Stairs (inverted), as lately performed at Windsor by her

Majesty’s servants”--“Election Day: a Poetical Sketch from

Nature”--The hustings--The chairing--John Sterling’s poem,

“The Election,” 1841--A New Election at Aleborough--Rival

Houses--The Candidates--The attorneys--A corrupt bargain--The

canvassing--Indirect bribing--The Bribery Act set at

naught--Female voters, a fanciful prospect by George

Cruikshank--“Rights of Women; or, a View of the Hustings with

Female Suffrage,” 1835--Memorable electioneering experiences:

Two eminent writers as candidates for seats in parliament,

1857--Incidents in the canvassing of James Hannay--W. M.

Thackeray’s contest at Oxford--Summary of bribery at elections:

Bribery Acts 374

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

SEPARATE PLATES.

PAGE

THE RIGHTS OF WOMEN; OR, A VIEW OF THE HUSTINGS WITH

FEMALE SUFFRAGE. 1835 _Frontispiece_

READY MONEY, THE PREVAILING CANDIDATE; OR, THE HUMOURS

OF AN ELECTION 84

THE HUMOURS OF A COUNTRY ELECTION. 1734 90

TO THE INDEPENDENT ELECTORS OF WESTMINSTER. VERNON AND

EDWIN. 1741 97

MEETING OF THE ASSOCIATION OF INDEPENDENT ELECTORS OF

WESTMINSTER: THE SPY DETECTED. MARCH, 1747 109

THE HUMOURS OF THE WESTMINSTER ELECTION; OR, THE SCALD

MISERABLE INDEPENDENT ELECTORS IN THE SUDS. 1747 113

GREAT BRITAIN’S UNION; OR, THE LITCHFIELD RACES. 1747 114

BRITANNIA DISTURBED BY FRENCH VAGRANTS. LORD TRENTHAM FOR

WESTMINSTER. 1749 121

ALL THE WORLD IN A HURRY; OR, THE ROAD FROM LONDON TO

OXFORD. 1754 134

THE OXFORDSHIRE ELECTION--THE POLLING BOOTH. 1754 145

“WILKES AND LIBERTY” RIOTS. THE SCOTCH VICTORY. MURDER OF

ALLEN BY A GRENADIER. MASSACRE OF ST. GEORGE’S FIELDS. 1768 174

THE HUSTINGS AT BRENTFORD, MIDDLESEX ELECTION, 1768. SERJEANT

GLYNN AND SIR W. BEAUCHAMP PROCTOR 178

SEQUEL TO THE BATTLE OF TEMPLE BAR--PRESENTATION OF THE LOYAL

ADDRESS AT ST. JAMES’S PALACE. 1769 201

MASTER BILLY’S PROCESSION TO GROCERS’ HALL--PARLIAMENTARY

ELECTIONS--PITT PRESENTED WITH THE FREEDOM OF THE CITY. 1784 264

THE APOSTATE JACK ROBINSON, THE POLITICAL RAT-CATCHER. 1784 265

THE RIVAL CANDIDATES--GREAT WESTMINSTER ELECTION. 1784 266

THE HANOVERIAN HORSE AND THE BRITISH LION. MARCH, 1784 268

THE WIT’S LAST STAKE; OR, THE COBBLING VOTER AND ABJECT

CANVASSERS 275

LORDS OF THE BEDCHAMBER 276

THE WESTMINSTER WATCHMAN 277

THE CASE IS ALTERED 281

THE PROCESSION TO THE HUSTINGS AFTER A SUCCESSFUL CANVASS 282

THE WESTMINSTER DESERTER DRUMMED OUT OF THE REGIMENT. DEFEAT

OF SIR CECIL WRAY. HUSTINGS, COVENT GARDEN, WESTMINSTER

ELECTION. 1784 284

LIBERTY AND FAME INTRODUCING FEMALE PATRIOTISM (DUCHESS OF

DEVONSHIRE) TO BRITANNIA. 1784 285

DEFEAT OF THE HIGH AND MIGHTY BALISSIMO CORBETTINO AND HIS

FAMED CECILIAN FORCES, ON THE PLAINS OF ST. MARTIN, ON

THURSDAY, THE 3RD DAY OF FEBRUARY, 1785, BY THE CHAMPION

OF THE PEOPLE AND HIS CHOSEN BAND 287

PROOF OF THE REFINED FEELINGS OF AN AMIABLE CHARACTER, LATELY

A CANDIDATE FOR A CERTAIN ANCIENT CITY 293

PACIFIC ENTRANCE OF EARL WOLF (LORD LONSDALE) INTO BLACKHAVEN.

1792 296

MEETING OF PATRIOTIC CITIZENS AT COPENHAGEN HOUSE, 1795.

SPEAKERS: THELWALL, GALE JONES, HODSON, AND JOHN BINNS 298

THE DISSOLUTION; OR, THE ALCHYMIST PRODUCING AN ÆTHERIAL

REPRESENTATION. WILLIAM PITT DISSOLVING THE HOUSE OF COMMONS.

1796 300

TWO PAIR OF PORTRAITS. PRESENTED TO ALL THE UNBIASED ELECTORS

OF GREAT BRITAIN. 1798 305

MIDDLESEX ELECTION, 1804. A LONG PULL--A STRONG PULL--AND A

PULL ALL TOGETHER 312

POSTING TO THE ELECTION; OR, A SCENE ON THE ROAD TO BRENTFORD.

1806 315

THE LAW’S DELAY. READING THE RIOT ACT. 1820 334

CORIOLANUS ADDRESSING THE PLEBS. 1820 338

ELECTION SQUIBS AND CRACKERS FOR 1830 346

HIS HONOUR THE BEADLE (WILLIAM IV.) DRIVING THE WAGABONDS OUT

OF THE PARISH. NOV. 28, 1830 354

LEAP-FROG DOWN CONSTITUTION HILL. APRIL 13, 1831 356

HOO-LOO-CHOO, _alias_ JOHN BULL, AND THE DOCTORS. MAY 2, 1831 357

LEAP-FROG ON A LEVEL; OR, GOING HEADLONG TO THE DEVIL. MAY

6, 1831 358

JOHN GILPIN. MAY 13, 1831 366

“THE HANDWRITING ON THE WALL.” MAY 26, 1831 367

VARNISHING--A SIGN (OF “THE TIMES”). JUNE 1, 1831 370

THE RIVAL MOUNT-O’-_Bankes_; OR, THE DORSETSHIRE JUGGLER. MAY

25, 1831 371

MAZEPPA--“AGAIN HE URGES ON HIS WILD CAREER.” AUG. 7, 1832 372

THREE GREAT PILLARS OF GOVERNMENT; OR, A WALK FROM WHITE

CONDUIT HOUSE TO ST. STEPHEN’S. JULY 23, 1834 376

INCONVENIENCES THAT MIGHT HAVE ARISEN FROM THE BALLOT 378

SMALLER ILLUSTRATIONS.

CANDIDATES ADDRESSING THEIR CONSTITUENTS _Title page_

WALPOLE CHAIRED. 1701 79

THE PREVAILING CANDIDATE; OR, THE ELECTION CARRIED BY BRIBERY

AND THE D----L 82

KENTISH ELECTION. 1734 86

THE DEVIL ON TWO STICKS. 1741 92

WESTMINSTER--THE TWO-SHILLING BUTCHER. 1747 111

THE ELECTION AT OXFORD--CANVASSING FOR VOTES. 1754 144

THE OXFORDSHIRE ELECTION--CHAIRING THE MEMBERS. 1754 147

GEORGE BUBB DODINGTON (LORD MELCOMBE REGIS) AND THE EARL OF

WINCHILSEA. 1753 149

BURNING A PRIME MINISTER IN EFFIGY. 1756 155

JOHN WILKES, A PATRIOT 159

A BEAR-LEADER. HOGARTH, CHURCHILL, AND WILKES 160

A SAFE PLACE. WILKES IN THE TOWER, 1763 162

THE NEW COALITION--THE RECONCILIATION OF “THE TWO KINGS OF

BRENTFORD.” 1784 254

A MOB-REFORMER. 1780 256

THE COALITION WEDDING--THE FOX (C. J. FOX) AND THE BADGER

(LORD NORTH) QUARTER THEIR ARMS ON JOHN BULL 263

BRITANNIA AROUSED, OR THE COALITION MONSTERS DESTROYED 264

HONEST SAM HOUSE, THE PATRIOTIC PUBLICAN, CANVASSER FOR FOX 266

MAJOR CARTWRIGHT, THE DRUM-MAJOR OF SEDITION 267

THE DEVONSHIRE, OR MOST APPROVED MANNER OF SECURING VOTES. 1784 270

EVERY MAN HAS HIS HOBBY HORSE--FOX AND THE DUCHESS OF DEVONSHIRE 282

FOR THE BENEFIT OF THE CHAMPION--A CATCH. DEFEAT OF THE

MINISTERIAL CANDIDATE, SIR CECIL WRAY, WESTMINSTER

ELECTION. 1784 283

ELECTION TROOPS BRINGING THEIR ACCOUNTS TO THE PAY-TABLE,

WESTMINSTER. 1788 290

AN INDEPENDENT ELECTOR 291

AT HACKNEY MEETING--FOX, BYNG, AND MAINWARING 299

THE HUSTINGS--COVENT GARDEN. 1796 301

THE FRIEND OF HUMANITY AND THE KNIFE-GRINDER 302

LOYAL MEDAL. 1797 305

THE WORN-OUT PATRIOT, OR THE LAST DYING SPEECH OF THE

WESTMINSTER REPRESENTATIVE, ON THE ANNIVERSARY MEETING,

HELD AT THE SHAKESPEARE TAVERN, OCTOBER 10, 1800 308

POLITICAL AMUSEMENTS FOR YOUNG GENTLEMEN, OR THE BRENTFORD

SHUTTLECOCK BETWEEN OLD SARUM AND THE TEMPLE OF ST.

STEPHEN’S. 1801 310

THE OLD BRENTFORD SHUTTLECOCK--JOHN HORNE TOOKE RETURNED

FOR OLD SARUM. 1801 310

BRITANNIA FLOGGED BY PITT--THE GOVERNOR IN ALL HIS GLORY. 1804 313

THE HIGHFLYING CANDIDATE, LITTLE PAULL GOOSE, MOUNTING FROM

A BLANKET--_Vide_ HUMOURS OF WESTMINSTER ELECTION. 1806 315

COALITION CANDIDATES--SHERIDAN AND SIR SAMUEL HOOD. 1806 316

A RADICAL DRUMMER. 1806. W. COBBETT 317

VIEW OF THE HUSTINGS IN COVENT GARDEN--WESTMINSTER ELECTION.

1806 318

PATRIOTS DECIDING A POINT OF HONOUR; THE DUEL AT WIMBLEDON,

BETWEEN SIR FRANCIS BURDETT AND JAMES PAULL. WESTMINSTER

ELECTION. 1807 320

THE POLL OF THE WESTMINSTER ELECTION, 1807. ELECTION CANDIDATES;

OR, THE REPUBLICAN GOOSE AT THE TOP OF THE POLL. ON

THE POLL: BURDETT, COCHRANE, ELLIOTT, SHERIDAN, PAULL;

BELOW ARE TEMPLE, GREY, GRANVILLE, PETTY, ETC. 321

THE HEAD OF THE POLL; OR, THE WIMBLEDON SHOWMAN AND HIS

PUPPET. 1807. TOOKE AND BURDETT 322

THE CHELMSFORD PETITION: PATRIOTS ADDRESSING THE ESSEX CALVES 323

THE FREEDOM OF ELECTION; OR, HUNT-ING FOR POPULARITY, AND

PLUMPERS FOR MAXWELL. 1818 332

HUNT, A RADICAL REFORMER 334

THE GHEBER WORSHIPPING THE RISING SUN. JULY 6, 1830 345

WILLIAM COBBETT--“PETER PORCUPINE” 348

SINDBAD THE SAILOR AND THE OLD MAN OF THE SEA. JUNE 8, 1883 375

DESIGN FOR THE KING’S ARMS, TO BE PLACED OVER THE SPEAKER’S

CHAIR. FEB. 17, 1835 377

A HISTORY OF PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS IN THE OLD DAYS.

CHAPTER I.

CONCERNING EARLY PARLIAMENTS AND ELECTIONS OF KNIGHTS AND BURGESSES.

The subject of elections being so indissolubly bound up with that of

parliamentary assemblages and dissolutions, it will not be out of place

to glance at the progress of that institution. John was the first

king recorded to summon his barons by writ; this was directed to the

Bishop of Salisbury. In 1234 a representative parliament of two knights

from every shire was convened to grant an aid; later on (1286) came

the parliament of Merton; and in 1258 was inaugurated the assembly

of knights and burgesses, designated the _mad_ parliament. The first

assembly of the Commons as “a confirmed representation” (Dugdale) was

in 1265, when the earliest writ extant was issued; while, according

to many historians, the first regular parliament met in 1294 (22 Edw.

1), when borough representation is said to have commenced. From a

deliberative assembly, it became in 1308 a legislative power, without

whose assent no law could be legally constituted; and in 1311, annual

parliaments were ordered. The next progressive step was the election

of a Speaker by the Commons; the first was Peter de la Mare, 1377. A

parliament of _one_ day (September 29, 1399), when Richard II. was

deposed, is certainly an incident in the history of this institution;

the Commons now began to assert its control over pecuniary grants.

In 1404 was held at Coventry the “Parliamentum Indoctum” from which

lawyers were excluded (and that must have offered a marked contrast

to parliaments in our generation). In 1407 the Lords and Commons

assembled to transact business in the Sovereign’s absence. Reforms

were clearly then deemed expedient: in 1413 members were obliged to

reside at the places they represented,--this enactment has occasioned

expense and inconvenience in obeying “the letter,” but appears to

have otherwise been easily defeated as regards “the spirit;”[1] in

1430 the Commons adopted the forty-shillings qualification for county

members. A parliament was held at Coventry in 1459; this was called

the _Diabolicum_. The statutes were first printed in 1483; in 1542

the privilege of exemption from arrest was secured to members; and in

1549 the eldest sons of Peers were admitted to sit in the Commons.

With James I. commenced those collisions between the Crown and the

representatives of the people which marked the Stuart rule. The Commons

resisted those fine old blackmail robberies known during preceding

reigns as “benevolences,” under which plea forced contributions were

levied by the Crown, especially during Elizabeth’s reign. James I.

pushed these abuses too far, in his greed for money.

The parliament of 1614 refused to grant supplies until grievances

were redressed; James dismissed them, and imprisoned several members.

This short session was known as the “Addled Parliament.” The “Long

Parliament” assembled in 1640, and the House of Peers was abolished by

it in 1649; and later on, a Peer sat in the Commons. This parliament,

proving intractable, was dissolved by Cromwell in 1653. Under Charles

II., with the restoration of monarchy, the Peers temporal resumed

their functions, and in 1661 the Lords spiritual were allowed to

resume their seats, and the Act for triennial parliaments was unwisely

set aside by the Commons. The relations between the Crown and the

Commons were again becoming strained in 1667, when an Act excluding

Roman Catholics from sitting in either House was forced through the

legislature. From this point the narrative of electioneering incidents

may commence, the more appropriately since it was at this time there

arose the institution of the familiar party distinctions of Whig and

Tory.

The orders for the attendance of members and the Speaker were somewhat

curious; for instance, among the orders in parliament regulating

procedure, the following are noteworthy:--

Feb. 14, 1606.--The House to assemble at eight o’clock, and

enter into the great business at nine.

May 13, 1614.--The House to meet at seven o’clock in the

morning, and begin to read bills at ten.

Feb. 15, 1620.--The Speaker not to move his hat until the third

_congée_.

Nov. 12, 1640.--Those who go out of the House in a confused

manner before the Speaker to forfeit 10_s._

May 1, 1641.--All the members that come after eight to pay

1_s._, and those that do not come the whole day to pay 5_s._

April 19, 1642.--Those who do not come to prayers to pay 1_s._

Feb. 14, 1643.--Such members as come after nine o’clock to pay

1_s._ to the poor.

March 21, 1647.--The Speaker to leave the chair at twelve

o’clock.

May 31, 1659.--The Speaker to take the chair constantly every

morning by eight o’clock.

April 8, 1670.--The back door in the Speaker’s chamber to be

nailed up during the session.

March 23, 1693.--No member to take tobacco into the gallery, or

to the table, sitting at committees.

Feb. 11, 1695.--No news-letter writer to presume to meddle with

the debates, or disperse any in their papers.

Orders touching motions for leave into the country:--

Feb. 13, 1620.--No member shall go out of town without open

motion and licence in the House.

March 28, 1664.--The penalty of £10 to be paid by every knight,

and £5 by every citizen, etc., who shall make default in

attending.

Nov. 6, 1666.--To be sent for in custody of the serjeant.

Dec. 18, 1666.--Such members of the House as depart into

the country without leave, be sent for in custody of the

serjeant-at-arms.

Feb. 13, 1667.--That every defaulter in attendance, whose

excuse shall not be allowed this day, be fined the sum of £40,

and sent for in custody, and committed to the Tower till the

fine be paid.

That every member as shall desert the service of the House

for the space of three days together (not having had leave

granted him by the House, nor offering such sufficient excuse

to the House as shall be allowed), shall have the like fine

of £40 imposed on them, and shall be sent for in custody, and

committed to the Tower; and that the fines be paid into the

hands of the serjeant-at-arms, to be disposed of as the House

shall direct.

April 6, 1668.--To pay a fine of £10.

A few words of explanation regarding technicalities will be found

in place, since the qualifications of voters have a distinctive

language of their own, used to indicate their various degrees of

electoral privilege. The terms, “burgage tenures,” “scot and lot,”

“pot-wallopers,” “splitting,” “faggot votes,” etc., occur constantly,

and it may be desirable to indicate in advance the meanings attached to

these enigmatical expressions.

Burgage tenures consist of one undivided and indivisible tenement,

neither created, nor capable of creation, within time of memory, which

has immemorially given a right of voting; or an entire indivisible

tenement, holden of the superior lord of a borough, by an immemorial

certain rent, distinctly reserved, and to which the right of voting is

incident.

Another qualification determined the right of voting “to be in such

persons as are seized in fee, in possession, or reversion, of any

messuage, tenement, or corporal hereditament within the borough, and in

such persons as are tenants for life or lives, and, for want of such

freeholds, in tenants for years determinable upon any life or lives,

paying scot and lot, and in them and in no other.”

Potwallers--those who, as lodgers, boil the pot. Pot-wallopers, or

Pot-boilers.

The word Burgess extends to inhabitants within the borough.

The right of election being generally vested “in inhabitants paying

scot and lot, and not receiving alms or any charity,” these terms

require explanation. What it is to pay scot and lot, or to _pay scot_

and _bear lot_ is nowhere exactly defined. According to Stockdale’s

“Parliamentary Guide,” compiled in 1784, it is probable that, from

signifying some special municipal or parochial tax or duty, they

came in time to be used in a popular sense, to comprehend generally

the burdens and obligations to which the inhabitants of a borough or

parish were liable as such. What seems the proper interpretation is,

that by inhabitants “paying scot and lot,” those persons are meant

whose circumstances are sufficiently independent to enable them to

contribute in general to such taxes and burdens as they are liable to

as inhabitants of the place. In Scotland, when a person petitions to be

admitted a burgess of a royal borough, he engages he will _scot_ and

_lot_, i.e. _watch_ and _ward_; and by statute (2 Geo. 1, c. 18, s. 9)

it is ascertained that in the election of representatives for the city

of London, the legislature understood _scot_ and _lot_ to be as here

explained.

As to the disqualifications, _alms_ means parochial collections or

parish relief; and _charity_ signifies sums arising from the revenue of

certain specific sums which have been established or bequeathed for the

purpose of assisting the poor. There are further nice distinctions in

the latter; for on election petitions persons receiving certain defined

charities were qualified to vote, while other charities disqualify

for the identical return. The burgage tenement decision which defines

the nature of this qualification as set down, arose on a controverted

election in 1775 for Downeton or Downton, a borough in Wilts, the

right of voting being admitted by both sides to be “in persons having

a freehold interest in burgage tenements, holden by a certain rent,

fealty, and suit of court, of the Bishop of Winchester, who is lord of

the borough, and paying reliefs on descent and fines on alienation.”

Thomas Duncombe and Thomas Drummer were the sitting members; and the

counsel for the petitioners, Sir Philip Hales and John Cooper, objected

to some twenty votes recorded for the candidates elected. “It was

proved that the conveyances to some were made in 1768, _i.e._ the last

general election, but that the deeds had remained since that time in

the hands of Mr. Duncombe, who is proprietor of nearly two-thirds of

the burgage tenements in Downton; so that the occupiers had continued

to pay their rents to him, and expected to do so when they became due

again, considering him as their landlord, and being unacquainted with

the grants made by him to the voters; and that there were no entries

on the court rolls of 1768 of those conveyances, nor of the payment

of the alienation fines. The conveyances to others appeared to have

been _printed_ at the expense of Mr. Duncombe, and executed after the

writ and precept had been issued, some of them being brought _wet_ to

the poll. The grantees did not know where the lands contained in them

lay, and one man at the poll produced a grant for which he claimed a

vote, which, on examination, appeared to be made to another person.”

The practice of making such conveyances about the time of an election

had long prevailed in the borough; the votes so manufactured were known