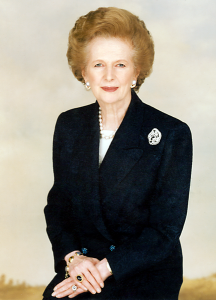

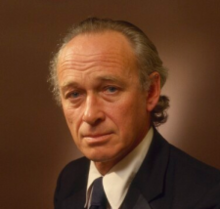

Below is the text of the speech made by Roy Jenkins, the then SDP MP for Glasgow Hillhead, in the House of Commons on 29 January 1986.

I beg to move,

That this House urges the Government to bring the United Kingdom into the Exchange Rate Mechanism of the European Monetary System forthwith.

The European monetary system, which this motion calls upon the Government to join forthwith, will be seven years old in a couple of months time. It was the most recent major initiative taken by the European Community and it was put into place remarkably quickly, partly because it did not involve a great series of interlocking individual decisions and therefore did not fall foul of any unanimity rules or even the need for a qualified majority.

I tried to relaunch the idea of a monetary route forward in a speech in Florence in the autumn of 1977. The European Council after that, in December, showed polite interest, but to say that there was any great sense of urgency or serious intent at that stage would be an exaggeration. The whole thing changed dramatically in the late winter and early spring. For most of its life the EMS has had to contend with the dollar being too high. Paradoxically, that changed because of the temporarily collapsing dollar in the early months of 1978. I vividly remember the occasion when I went to Bonn and Helmut Schmidt told me that he had changed his mind and he thought it was essential to go forward straightaway. He believed that he could get it on board as soon as the French legislative elections, due that year, as this year, were out of the way. So it happened.

The scheme was unveiled at the Copenhagen European Council that spring and was in place exactly a year later. I do not think there is serious doubt about its limited but substantial success for the participating countries. It has established the fact that it is a lasting entity, despite the fact that the buffeting waves of a violently fluctuating dollar, in particular, have been much greater than anybody expected when the scheme was being put into place. The EMS has survived well.

There have been many changes of central rates affecting nearly all the currencies in varying degrees but they have been carried through remarkably speedily and smoothly. That is a dramatic contrast to the delayed and traumatic devaluation under the otherwise admirable Bretton Woods system. Those changes have gone through with remarkable speed. When the Foreign Secretary held the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer he presided over a number of meetings of the Economic Monetary Council which put them through. That is an extraordinary example of presiding from outside over a thing which was working extremely well internally.

Some of the changes have not been such as to render the system nugatory. The Italians asked specially for a wider margin of 6 per cent. either way for the lira compared with the margin of 2·25 per cent. for the other participating currencies. When the Italian lira moved sharply last July, that was the first move for three years. The idea that there has been constant instability and change is certainly not true.

The fairly recent International Monetary Fund study calculates that the EMS has taken about 30 per cent. off the fluctuations between the participating currencies that would have occurred otherwise. That has been extremely valuable, particularly in view of how much Europe has been plagued by currency fluctuations within the Community, especially in the mid-1970s. This is one of the things that set my mind moving in this direction in 1977. Europe had been doing well throughout the 1960s and the early 1970s compared with America or Japan, but in the mid-1970s it suddenly started to do much worse. I was convinced that one of the major reasons was that the 1960s and early 1970s were a time of relative currency stability in the world, whereas the late 1970s were a time of violent currency and exchange rate fluctuations. That was internal, in Europe—outwith Japan and the United States. There was a considerable effect, but it was external to those countries.

In addition, there has been a remarkable recent development in the past couple of years in the private use of the ecu, paradoxically, perhaps, more than in the public use of the ecu. It is now a major borrowing and lending currency.

Therefore, there is no question but that the system which, by our own choice, we are outside, is successful. I think that all the participants value it and other potential participants are eager to join it. For instance, Senor Gonzalez told me just before he came into the Community that he believed that he could bring forward by a year the date of Spanish adherence to the EMS, and he would regard that as very desirable from the point of view of full Spanish membership of the Community and influence within the Community. We might well take a little notice of that point.

How was it that we did not join at the beginning? Three countries had doubts, although at slightly different stages. Italy and Ireland went away from the last European Council leaving serious doubts as to whether they would join. Then they took their courage in both hands and cam:, in. I am sure that neither of them has regretted that decision at all. Why not us? I heard the reasons given by two successive Governments. Indeed, they are engraved on my mind. I remember that in November 1978 I went to see the right hon. Member for Cardiff, South and Penarth (Mr. Callaghan), and he assured me that, in principle, he would like the Labour Government to bring Britain into full participation in the exchange rate mechanism. However, he added, “I am extremely worried at being locked in at too high a rate, which would inhibit our ability to deal with unemployment.” Almost exactly six months later I went to see the right hon. Lady who still presides over the Government, and she assured me that in principle she was extremely anxious for Britain to be a full participant, but, she said, “I am extremely worried about being locked in at too low a rate, which would inhibit our ability to deal with inflation.” So we did not join. As a matter of fact, all the participating countries had lower unemployment and lower inflation than we did in the two years that followed.

Therefore, it is difficult to believe that such fears—no doubt legitimate—as well as an endemic offshore mentality were not at work in both those Governments. That worked still more strongly than the reasons given. It was careless and sad that we should have repeated for the third time the mistake of joining late. We did so with the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951 and the European Community in 1957. If one is joining an organisation it is sensible, if possible, to be there at the beginning because one can influence the organisation’s shape. It is better to do that than to stand aside for the third time, never learning the lesson, and saying that the shape does not fit, when one has not been there to influence its creation.

Mr. Douglas Hogg (Grantham)

Will the right hon. Gentleman comment on the point that the volatility of sterling, because it is an oil currency, makes membership of the EMS more difficult for this country than for the non-oil economies?

Mr. Jenkins

That will make British membership more difficult for the European monetary system rather than for this country. In a way, we are lucky that it has been, and is still, willing to have a more volatile currency in full membership. We want to try to control the volatility of sterling as much as we can.

In view of the fear of the right hon. Member for Cardiff, South and Penarth—[Interruption.]—what happened to sterling subsequently—(Interruption.]—

Mr. Deputy Speaker (Mr. Ernest Armstrong)

Order. If the hon. member for Bolsover (Mr. Skinner) wants to intervene in the debate, he should come into the Chamber.

Mr. Jenkins

Following the fear of the right hon. Member for Cardiff, South and Penarth that he would be locked in at too high a rate, what happened was that, with us outside the EMS, sterling appreciated beyond the wildest fears of anybody in 1978–79. Over two years it rose from $1·60 to $2·40. The result was that our competitive index worsened by 60 per cent., on the scale measured by the IMF. The result of that was the destruction of one fifth of our manufacturing industry and the associated increase in unemployment.

Nobody should suggest that membership of the EMS would have obviated all that. However, I believe that it would have reduced it substantially. It is a great mistake to believe that any monetary scheme or monetary mechanism can or perhaps should resist the long-term swell of the currency ocean. It can substantially take the top off the waves, particularly when, as happens too often, exchange rates are reacting not to differing levels of inflation, not to differing rates of productivity growth, not to trade imbalances, but much more to changes of sentiments or capital flows. The monetary system can do a great deal to cut the top off such waves.

That was very much the case in 1980. Everybody knew that rate could not be sustained. It was just a question of when it came down. If we had been in the EMS, the bubble would have been pricked much more quickly, and the damage to our industry and employment would have been much more limited. We would have avoided much of the ridiculous parabola in the sky of sterling going up from $1·60 to $2·40 and then coming down within 18 months back to $1·60, and, for a short period, down to $1·07.

Mr. Nigel Spearing (Newham, South)

I should like to take the right hon. Gentleman back to some of the possible disadvantages he mentioned in relation to my right hon. Friend the Member for Cardiff, South and Penarth (Mr. Callaghan). Is it not a fact that the EMS is much more than a smoothing insurance mechanism? Are there not potential disadvantages in a Government’s requirements in respect of a general economic policy to maintain parities? Is not the ruling mechanism—that of the central banks—likely to create difficulties for any member Government which they might not have if it were not a member of the system, bearing in mind particularly the strength of the Bundesbank and of the market?

Mr. Jenkins

I hear the hon. Gentleman and his colleagues, but I think that the hon. Gentleman has himself complained about how British economic policy has developed over the past seven years. He has complained that we have had by far the highest unemployment rate in years. I do not understand how his dedicated, dogmatic anti-Europeanism can lead him to say that he would rather have what has happened outside the EMS than operate on a co-operative basis. In my view, we would have been able to avoid a significant part of the sterling fluctuation. That would have given us a substantial and healthier base for our economy.

I have been dealing in detail largely with the past. I shall now consider the position today. Although it would be better to enter the exchange rate mechanism at any time than never to enter it at all, there are obviously some times when it would be much better to enter. This is a very good time because there is a particular conjunction between the sterling-dollar rate and the sterling-deutschmark rate. Those are the two factors of primary importance at which people have been looking in seeking the most favourable juncture.

Last February, 11 months ago, there was a good occasion. The right hon. Member for Guildford (Mr. Howell) noted that in his interesting publication, which I read carefully. That opportunity was allowed to slip away, but now there is another good occasion. The pound is approximately 3·33 deutschmarks, down from 3·75 a month ago — a devaluation of more than 11 per cent. against a major European currency.

I believe that most of the decreases in oil prices may have occurred. The price was $30 a barrel in November. The price is moving, but let us assume that it settles down somewhere between $17 and $20 a barrel. We will have a very uncertain market, but at least the really substantial move has probably occurred.

Sentiment in the oil markets is very uncertain, and the price is likely to fluctuate with every rumour about what Saudi Arabia is going to do, or about the date of the next OPEC meeting. The problem is how to tame the impact of the short-term changes in sentiment without hopelessly disrupting the domestic economy.

Outside, interest rates are almost the Government’s only weapon. If we were fully in the EMS, support from our partners would provide an alternative means to manage short-term fluctuations. We would have a much better chance of living through a period of see-sawing expectations without disruptive alterations to either exchange or interest rates.

Mr. Anthony Beaumont-Dark (Birmingham, Selly Oak)

I am following the right hon. Gentleman’s argument with great interest. He talked about interest rates and the damage that fluctuation of the pound has done to manufacturing industry. The right hon. Gentleman knows Birmingham almost as well as I do, so he realises the effects. Control of the EMS would not rest on good will, which does not exist between central banks—only logic does. Because of what has happened to the pound as a result of the influence of the petrocurrency, and because of the present interest rates structure, would not interest rates be 2 to 3 per cent. higher now if we had been in the EMS? Would that not be more dangerous for us than the present system?

Mr. Jenkins

I think that interest rates would be lower if we were in the EMS. I would not say that interest rates would in all circumstances be lower in the EMS, but I would say at the present time in my view—one can only express one’s own view—interest rates would be lower, and the immediate prospect would be one of lower rather than higher interest rates.

Mr. Tony Blair (Sedgefield)

The motion says that we should forthwith join the exchange rate mechanism. Suppose we had joined in October or November last year and the best rate we could have achieved was 3·60 or perhaps 3·50 deutschmarks to the pound. Considering the pressure on the pound last week, is it not the case that we would have been raising interest rates?

Mr. Jenkins

I am saying that we are now at the best juncture we have reached for some time. There have been other good ones. I would not have joined last October. I would have joined last February—

Mr. Dennis Skinner (Bolsover)

The right hon. Gentleman said “at any time”.

Mr. Jenkins

I said it is better to get in, rather than never to get in. Over the past seven years we have become like lift dwellers in a department store. We have gone into the lift, and it has gone up and down past every floor. The attendant has called out, “Soft furnishings, hard furnishings, sports goods, toys” and we have said “No, we want none of those.” We always want to move on to the next floor. Lifts are very useful objects, but they are not suitable for permanent living. If one is always to say that there is never the perfect opportunity and thus try to get out before it is suitable, it would be more advantageous to get out on the floor that suits one, rather than on the floor that does not suit one. I would not stay in the lift indefinitely, and that is what the policy of the Government is about.

Apart from the short-term fluctuating position, there is also the medium and long-term position, and without the oil price shocks of recent weeks we would anyway have been in for a rough landing as our oil surplus runs down. What I am saying is that our huge surplus of oil will certainly be given to Russia, and it seems to me that we greatly want the assistance, if we can have it, of our other European partners to try and make that landing smoother. Be in no doubt that having reserves 10 times ours, which are those that are at the disposal of the EMS, is a considerable benefit. We are lucky that they still want us in.

Why do they? I think the reason bears upon another more general reason. They want us in more because of the importance of the City of London as a financial centre, rather than because of the importance of sterling as a currency. It is not nearly as important as the deutschmark.

It is greatly in the interests of every trading country and every economy to make sense of the world monetary system. Be in no doubt, with the fluctuations that we have had recently — and I am in favour of changes in currency rates which reflect realities in the performance of different economies—nobody is suggesting that we can or should resist the violent changes which make the free-floating rate the enemy of international trade, of international investment flows, and bring into being the grave danger of creating protectionist forces to a strong degree with currencies such as the dollar, which are forced up and kept at artificial lengths for some time. I do not think we can possibly put Bretton Woods back on its pedestal again, but we can create a tripod of greater stability, and if we are to do that, it manifestly has to be on the basis of the dollar, the yen, and the ecu as the currency of the European system.

As long as Britain is outside the mechanism, the European leg of the tripod will be hobbled by the absence of the City of London more than by the absence of sterling. It is as though New York and Chicago were outside the dollar area. That is why Britain is still welcome in the exchange rate mechanism. It is also an additional reason why we should be in favour of entering it. Enlightened self-interest is our motive for getting some sense and stability back into the international monetary system.

I am convinced that so long as Britain remains outside the ERM—outside the only major Community initiative in the past 10 years— and so long as she manifestly repeats the old habit of 1951 and 1957, we shall inevitably diminish our influence on other matters concerning the European Community. Spain noticed that fact as soon as she entered the EEC. She said, “We want to have full influence and we must be a fully participating member.” It is curious that somehow we cannot see that.

On direct and indirect grounds, the case is strong. The moment is as good a one as we are likely to get. I urge the Chancellor to overcome what I fear has now become the Prime Minister’s prejudice and, in accordance with what is now a substantial balance of informed opinion, to get on with it.