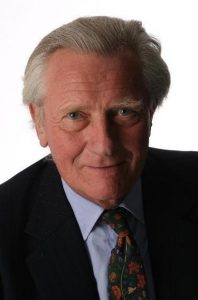

Below is the text of the speech made by John Cartwright, the then SDP MP for Woolwich, in the House of Commons on 12 December 1985.

I am grateful for the opportunity to raise the issue of the intended closure of St. Nicholas hospital. I am also grateful for the visible support of the hon. Member for Erith and Crayford (Mr. Evennett). I hope that he will have the opportunity of catching your eye, Mr. Deputy Speaker, in the course of the debate. If he does, he may speak not only for himself but for his hon. Friend the Member for Bexleyheath (Mr. Townsend). I appreciate and value the support that the hon. Members have given in the campaign on behalf of St. Nicholas hospital. Their support has demonstrated that this is an all-party campaign, and underlines the fact that the hospital serves not only my constituency but neighbouring areas.

This is the third occasion on which I have raised the question of the future of St. Nicholas hospital on the Adjournment. That illustrates the long-standing campaign waged against it by Health Service officials and the sheer determination of local people to keep it open.

It is worth putting the current problems into perspective. The first formal attack on St. Nicholas came as long ago as 1971 from the former south east regional hospital board. Its plan died with the board’s demise in 1974, but the vendetta against St. Nicholas continued. The new Greenwich and Bexley area health authority issued a formal consultation document in November 1976 proposing the removal of all acute services from St. Nicholas. Despite massive public opposition, the closure of all beds at the hospital was confirmed by the authority in July 1977. The problem then landed on the desk of the Secretary of State the present Lord Ennals. To his credit, he received several deputations, consulted widely and visited Plumstead to see for himself, not just the hospital but the area it serves. As a result he declared in December 1977:

“I do not believe it can be right to close the hospital and I am unwilling to do so.”

He justified that decision by producing what is arguably the most quoted statement about the hospital in its long and distinguished history. He said:

“St. Nicholas is a valued hospital, well situated to service a community whose population is growing. It is in Plumstead where social conditions are poor and there are many old people living in bad housing. It is also central for Thamesmead, a locality of industrial development.”

In May 1978 after further detailed discussions and some deliberation, the Secretary of State announced his final decision. He endorsed the plan put forward by the South East Thames regional health authority. It was intended to turn St. Nicholas from a district general hospital into a community hospital. The blueprint for the transformation was clear and detailed. In its new role, the hospital was to provide, in the words of the then Secretary of State,

“out-patient and minor casuality facilities; theatre and supporting services for minor surgery with about 20 beds; 20 to 25 general practitioner medical beds; and the present 41 geriatric beds with perhaps the addition of some further geriatric beds. Consideration should also be given to the establishment of a psycho-geriatric day centre.”

I admit that I was disappointed and somewhat cynical about that outcome. To me, trusting St. Nicholas to the tender mercies of those Health Service mandarins who had always wanted to close it was about as sensible as trusting Little Red Riding Hood to the wolf.

Lord Ennals did his best to reassure me. In a personal letter dated 10 July 1978, he wrote:

“I really do not think it right to contend that the change of use of St. Nicholas hospital means its eventual closure. I told the health authorities that I am not willing to agree to closure and I know that they will make every effort to develop practicable arrangements which will enable the hospital to continue. I cannot believe that the inevitable transitional problems cannot be solved and I am sure that St. Nicholas can become a viable community hospital which will complement the District General Hospitals in the Area and give valuable service to the people of Plumstead and Thamesmead.”

Unfortunately, my pessimistic forecast turned out to be more accurate than Lord Ennals’ optimistic predictions. It was only four years after his decision that the health authority once again recommended total closure of the hospital. In the meantime, it had never allowed the hospital even to try to carry out the tasks that the Secretary of State had mapped out for it. It starved it of resources, refused to let it provide the range of services included in the 1978 decision, and, far from developing the hospital, pursued a policy of systematically removing one after another of the vital elements of the 1978 package.

First came the closure of a minor surgery department. Then the number of general practitioner beds was cut. A continued rundown of out-patient facilities culminated in the transfer of two ear, nose and throat clinics to the Brook hospital. Then came the abrupt closure of the “walking wounded” accident department. In none of those cases was there any public consultation. The closures were regarded as temporary, and not therefore subject to the formal procedures. In act, they were widely seen for what they were—a deliberate campaign by the Greenwich health authority to run down St. Nicholas by back-door cuts and thus to achieve the total closure that it had been denied in 1978.

In 1982 people in the authority finally took their courage in both hands and once again started the formal procedure to shut down the hospital. Then they became embroiled in a complex argument with the Bexley health authority over the division of the financial spoils expected to result from closure. That arose because between 60 and 66 Bexley patients are being cared for in geriatric beds in Greenwich hospitals. Bexley wants to provide for them in its own area, but it cannot do so until it gets its hands on a substantial slice of cash from Greenwich. The Bexley plan was to provide extra geriatric beds at Queen Mary’s hospital in Sidcup and to create 26 new beds at Erith and district hospital, originally by 1988–89. However, we now hear that the Erith scheme is being put back, apparently as far into the future as 1993–94. Bexley is therefore left with a maximum of 34 geriatric beds at Queen Mary’s in Sidcup in which to accommodate some 60 to 66 patients now in Greenwich.

Most people would regard that as too much of a tight squeeze, but Bexley health authority officials apparently believe that it is possible because what they charmingly call their throughput is considerably higher than that of Greenwich. That seems a somewhat insensitive approach to the care of the elderly and a rather doubtful proposition. It also totally ignores the fact that many of those elderly folk come from Erith, Belvedere and Welling in the northern part of the borough, an area which is far better served by the nearby St. Nicholas hospital than by one in faraway Sidcup. In fact, I understand that some elderly people discharged from Queen Mary’s hospital in Sidcup find their way into private nursing homes, and as a result are even further away from their homes and relatives than in Sidcup.

The Bexley patients are vital to the future of St. Nicholas hospital. If beds cannot be found for the old folk who are now cared for in the Brook and Memorial hospitals in Greenwich, the space that is needed will not be released to accommodate the Greenwich patients who now occupy St. Nicholas hospital beds.

The negotiations between the two district health authorities have been a long and drawn out affair. As long ago as 17 December 1984 the hon. Member for Oxford, West and Abingdon (Mr. Patten), in his role as a Department of Health and Social Security Minister, wrote to me and said:

“I am concerned that there should not be any further delay in making the decision on the future of St. Nicholas. It is important that Greenwich and Bexley health authorities agree between themselves at an early date on the amount of revenue to be transferred for geriatric services currently provided to Bexley residents from St. Nicholas. I will ensure that South East Thames Regional Health Authority is ready to arbitrate between the two authorities if agreement is not reached soon.”

I understand that the negotiations are still not complete. The Minister gave that assurance over a year ago. Nobody can accuse the authorities concerned of intemperate haste.

May I offer what I hope will be a sensible and helpful suggestion to the Minister. Given that the Erith provision will not be available until 1993–94, is it not possible to provide funds to enable the Bexley health authority to take over beds in St. Nicholas? There is plenty of accommodation in St. Nicholas. Could not some of the beds there be allocated to Bexley to provide for those old folk who will otherwise have to be accommodated at Queen Mary’s hospital?

I very much welcome the action that the Minister has taken so far. He has not rubber stamped the closure decision; he has asked serious questions about the future of patient care if St. Nicholas is closed. It is not just geriatric patients who will be affected. In its comments upon the closure proposal, the Greenwich and Bexley family practitioner committee questioned the sense of spending considerable capital sums upon providing extra outpatient and paramedical facilities in other hospitals if St. Nicholas was closed, particularly if this would involve patients in long and difficult journeys. The family practitioner committee supported at the very least the retention of full outpatient and diagnostic services at St. Nicholas.

It is also worth recalling that 54 local general practitioners who had used the general practitioner beds at St. Nicholas oppose both the closure and the resulting transfer of those beds to Greenwich district hospital. Their comment was revealing. They said that there was a crying need for beds for the elderly, whose primary need was care rather than high technology medicine or surgery. St. Nicholas could play that complementary, supportive role, with great benefit to the two district general hospitals. Many of the routine, minor accident cases could be dealt with at St. Nicholas instead of lengthening the queues at the Brook or the Greenwich district hospitals. The pressure on beds at the two big general hospitals could be eased if none acute cases and care were available at St. Nicholas.

My constituents are incensed by the fact that St. Nicholas is not being allowed to fill this role. They want to know what on earth the point is of lengthy and detailed public consultation if a health authority can then ignore its results as blatantly as the Greenwich health authority has done in this case. St. Nicholas is ideally sited to serve not just my constituents in Plumstead, Abbey Wood and Thamesmead but many more people in the neighbouring areas of Belvedere, Welling and Erith. It is ridiculous that these potential patients and their families should be forced to undertake costly and difficult journeys to Sidcup, just because of the bureaucracy of health service boundaries.

We are not asking for the hospital to be retained in its present form. We understand that the nature of the site makes it extremely expensive to run, but it should be possible to use some of the buildings and some of the land to provide the basic essentials that are needed by a viable and effective community hospital. That would release a substantial area of land to help with the funding of the necessary capital expenditure.

None of the factors that led Lord Ennals to rule against the closure in 1978 has been removed. The population is still growing, particularly in Thamesmead. There are still large numbers of elderly people. There are still substantial areas of old housing. And growing unemployment has done absolutely nothing to improve the social deprivation in the area. If anything, the case for St. Nicholas is stronger today than it was in 1978.

I applaud the Minister for the action that he has taken so far. I urge him to follow the example of his distinguished predecessor and come and see for himself. He will find that the case for St. Nicholas rests not on loyalty to a much loved local institution, powerful though that is, but on the sheer hard fact of the need for health care in the area that St. Nicholas has served for so long and that it should be able to serve in the future.