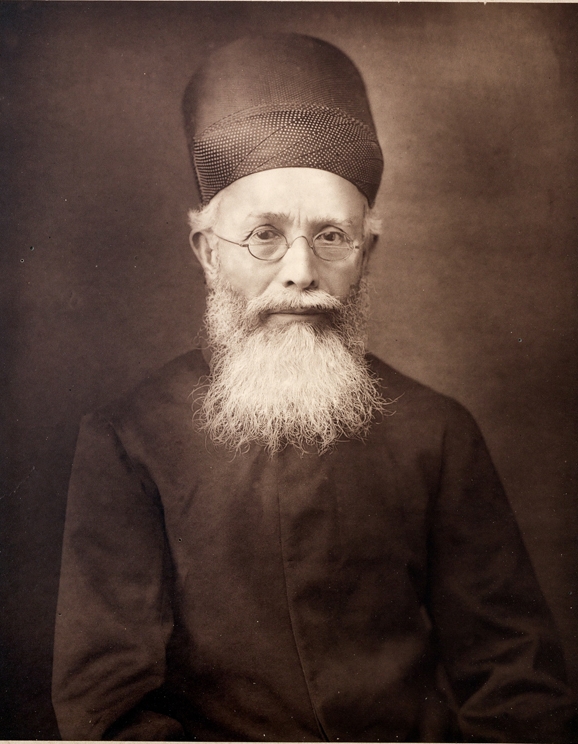

Below is the text of the speech made by Dadabhai Naoroji, the then Liberal MP for Finsbury Central, in the House of Commons on 20 September 1893.

Forty years ago, when I first spoke upon this question, I expressed my faith that the British people were lovers of justice and fair play. After those 40 years, and with an intimate acquaintance with the people of this country, and a residence of 38 years, I repeat that faith. I stand here again in that faith, ten times stronger than ever it was before—that the British people are lovers of their Indian subjects—and I stand here in that, faith hoping that India will receive justice and fair dealing at the hands of this Parliament.

I might also add, Sir, that from that time to the present I have always held that the British rule is the salvation of India. A higher compliment I cannot pay to the British rule. It has done a great many good things, and has given new political life to India. If certain reforms that can be made, and about which there was no difficulty, are brought about, both England and India will be blessed. I do not want to occupy much of your time, so I will not say more on this point.

I acknowledge with the deepest gratitude that so far, in several respects, though not in all, the English rule in India had been a great and an inestimable blessing. With regard to the Amendment I propose, in which I ask that a Royal Commission be appointed in order that we may come to the bottom of many questions of grievances, and especially into the principle and policy of the British rule as it exists at present, I may just quote a few words that were uttered by the right hon. Gentleman the Prime Minister only a few days ago in connection with the question that is before us. He says— I must make an admission. I do not think that in this matter we ought to be guided exclusively—perhaps even principally—by those who may consider themselves experts.

It is a very sad thing to say, but unquestionably it happens not infrequently in human affairs, that those who ought, from their situation, to know the most and the best, yet from prejudice and prepossessions know the least and worst. How far that is applicable to the Indian administration I am not undertaking to say; that is exactly what the inquiry ought to settle—whether the views expressed by the Anglo-Indian officials are the right views, or whether they are mistaken in the way the Prime Minister thinks they may be. He says, again— I certainly, for my part, do not propose to abide finally and decisively by official opinion. Independent opinion—independent but responsible—is what the House wants in my opinion in order to enable it to proceed safely in the career upon which, I admit, that it has definitively entered. And that is exactly what I appeal to.

In the matter of the difference of opinion that exists between the Indian officials on the one hand and the native opinion on the question it is absolutely necessary—especially in the case where this House cannot in any way watch the taxes and the taxpayers, which it cannot at a distance of 5,000 miles—it is absolutely necessary that there should be some independent inquiry to satisfy this House and the public whether the administration is such as it ought to be.

I hear that grumbling has begun to come from India itself. Only the other day, the 15th June, a telegram appeared in The Times saying that there seemed to be little doubt that all classes of India would soon join in demanding a strict and impartial inquiry into the excessive cost of the Indian establishments and the contributions levied on the Indian Treasury by the War Office, the Admiralty, and the Foreign Office; it was universally felt that India has been treated very unfairly in these matters, and that any attempt to stifle or delay the inquiry would cause much bitterness and discontent. Now, this is not all that has to be inquired into.

I say that the whole policy and principle of the Budget, and the whole administration requires an overhauling. The last inquiry we all know took place in 1854. Since then there has not been an inquiry of the same kind. When we see the Prime Minister himself acknowledging only a few weeks ago, on the 30th June, that the expenditure of India, and especially the military expenditure, is alarming, and when we see also the Finance Minister telling us in his last speech— The financial position of the Government of India at the present moment is such as to give cause for apprehension, I think it will be admitted by the House that the time has come when it is exceedingly necessary that some fair inquiry ought to be made into the state of affairs.

Well may the Prime Minister say that the expenditure is alarming, when we see that in 1853 and 1854—when the last inquiry took place—the annual expenditure of India was £28,000,000, whereas now in 1893 and 1894, excluding everything connected with public works, railways, &c, we have an expenditure of Rx68,000,000, which means an increase of 140 per cent. upon the expenditure of 1853 and 1854 in 40 years. The question is, whether this expenditure is justifiable or not?

No inquiry has been made during these 40 years, and it is time, with such an additional expenditure, that full inquiry ought to be made. And then we know, at the same time, that from the beginning of this century to the present day there has been a constant wail and complaint that India is poor; and when we remember that the latest Finance Ministers emphatically laid down that it is the poorest country in the world, even compared with Turkey in Europe, I think it will be enough to satisfy the House that there ought to be a proper inquiry. I will now take a few illustrations of the principles on which the Budget, as it were, is built up, and consequently which also is an indication of the principles and policy of the whole administration.

I have here the Colonial Office built at an expense of £100,000; every farthing of which is paid from the British Exchequer. I have the India Office built at nearly or about £500,000; every farthing of which is taken out of the Indian Exchequer from the Revenue of the poorest country in the world. The Colonial Service is given in the finance accounts as about £168,000; every farthing of which is paid from the British Exchequer. The Indian expenses or establishments given in the India Office expenditure is something like £230,000; every farthing of which is taken from the Indian Exchequer.

But there is one item which, small as it is, is peculiarly indicative of the curious relations between England and India. I refer to the examinations that take place in England to send out young men for service in India, where they get a splendid career. They inflict upon us, rightly or wrongly—I am not discussing the justifiableness of such an injury—injuries of six different kinds. They take the bread from the mouths of the natives; they take away from the natives the opportunities of service in their own country which they otherwise would have. That is the material welfare we lose.

They take away also esteem and the wealth of experience, because when an English official of 20 or 40 years’ experience leaves the country all his accumulated wisdom is utterly lost to us, and we do not get the benefit of the wealth of that wisdom which we have a right to from the experience of those who are serving in India. The result of that again is that we have no opportunity of exercising our faculties, or of showing our capacity for administration. So that I think, as a law of nature, our capacity is stunted, we lose and wither, and we naturally become, as it were, incapable in time of showing that we have capacity for government. And what follows? You add insult to injury.

After stultifying our growth, our mental and moral capacity, we are told that we are not capable. Well, Sir, I cannot, of course, enter into the details of these various injuries we suffer; but I say that here are these English youths who are to go out to India for a splendid career, and yet for their examination and further education in this country India must be charged £18,000 a year. This is a significant example of the relations that exist between India and England.

Lastly, I will give one more authority. Lord Hartington has put the case very significantly. He once said— There can, in my opinion, be very little doubt that India is insufficiently governed. I believe there are many districts in India in which the number of officials is altogether insufficient, and that is owing to the fact that the Indian Revenue would not boar the strain if a sufficient number of Europeans were appointed. The Government of India cannot afford to spend more than they do on the administration of the country; and if the country is to be better governed that can only be done by the employment of the best and most intelligent of the natives in the Service. I want to point out this as an illustration of the relations that subsist between England and India.

I need not say anything about the saving of £2,000 in the salary of Lord Kimberley, by appointing him also as the President of the Council. Much has been said on this point, so I will not add to it. By one stroke of the pen about 10,000,000 rupees additional burden is put on the poor taxpayer of India by giving a British exchange of 1s. 6d. to the European officials. This means this, that the starving are to be starved more in order that the well-fed may have their fill.

I think the House will ask whether such should be the relations between the two Revenues? To come to the next proposition. Another illustration of what I am saying is charging India with half the expense of the Opium Commission. I will not say much upon that subject, because I find that almost the whole of the English Press, as well as the Indian Press, have condemned that proposal, and have used strong words, which I should be unwilling to use—that is to say, the English Press has used very strong words against that proposal, and I will only use the softer and milder word—that it is unjust.

It was the English people, in the interest of what they consider their own morality, who proposed that this Commission should be instituted, and it must be remembered that it was this House that had settled that such a Commission should be given. Under such peculiar circumstances, to ask the people of India to pay half of this expense is anything but just. And what is still more striking is this—that in 1870 the same question was before this House, and then the right hon. Gentleman the Prime Minister, and in 1891 the Leader of the House (Mr. W. H. Smith), laid it down distinctly that India should not suffer in the slightest way; that unless the House was prepared to give to India the surplus of £6,000,000 of 1870 to make up the deficit of every year in Indian Revenue, neither the Prime Minister nor the Leader of the House in 1891 (Mr. W. H. Smith) would proceed any further, or would listen to any representation about it. After such just protest against any movement of that kind, that the Prime Minister should now agree to this proposition is, I must confess, altogether beyond my comprehension.

The next illustration, and a very significant one, is one upon which I need not dwell long, because only a short time ago a Debate took place in the House of Lords on the subject of military expenditure, when. Lord Northbrook, who has been Viceroy of India; the Duke of Argyll, who has been a Secretary of State; Lord Kimberley and Lord Cross were present, and it was the unanimous opinion of their Lordships that the Treasury and the War Office had treated India very unjustly in respect of the military expenditure and upon expeditions.

I will read one extract from Lord Northbrook to show the manner in which India is treated in that respect. The whole Debate is worth a very careful perusal, and if hon. Gentlemen of this House will peruse that Debate they will get some idea of what highest Indian officials think of the relations of England with India. I will read one extract of Lord Northbrook’s speech, which is very significant.

He said— The whole of the ordinary expenses in the Abyssinian Expedition were paid by India, only the extraordinary expenses being paid by the Home Government. I may interpose that, had it not been for the agitation I raised on that occasion, there is no doubt that the Indian Government would have been saddled with the whole of that expense. As it is, they had only to pay the ordinary expenses, and the British Government to pay the extraordinary expenses, though we had nothing to do with that. Lord North-brook goes further.

He goes on to say— The argument used being that India would have to pay her troops in the ordinary way, and she ought not to seek to make a profit out of the affair. But how did the Home Government treat the Indian Government when troops were sent out during the Mutiny? Did they say—’We do not want to make any profit out of this?’ Not a bit of it. Every single man sent out was paid for by India during the whole time, though only temporary use was made of them, including the cost of their drilling and training as recruits until they were sent out. I think this is a significant instance of the relations between England and India, and I hope the House will carefully consider its position.

In regard to the injustice of the military expense, even a paper (The Pioneer), which takes the side of the Government against the Indians generally, has expressed the opinion that the sum now imposed is an injustice, and that the expense is a large item annually increasing. It gives the whole—I think £2,200,000 in all—and then says— This sum is a terrible drain on the resources of India, and might well be reduced. One more significant instance of these things. When the Afghan War took place it was urged upon this House that it was an Imperial question; that the interests both of England and India were concerned in it; and it was right and proper that this House and this country should take a fair share in the expenditure of that war.

The right hon. Gentleman the Prime Minister accepted the view which Mr. Fawcett put forward, and he said— In my opinion, my hon. Friend the Member for Hackney has made good his case. And he says again that it is fair and right to say that, in his opinion, the case of his hon. Friend the Member for Hackney is completely made good, and that case, as he understood it, had not received one shred of answer.

Well, Sir, the case was then that this war had taken place in which both India and England were equally interested; that as it was an Imperial question, and not altogether an Indian question, a portion of the expenses ought to be defrayed by this country. And the right hon. Gentleman the Prime Minister, true to his word, when he came into power, did contribute a certain portion on that ground. We might have expected that he would have contributed half of it, but he contributed nearly a quarter; out of an expenditure of £20,000,000 or £21,000,000 he contributed from the British Exchequer £5,000,000, for which I can assure the House we are most grateful, not so much for the sake of the money, but because the principle of justice was admitted. It was admitted that this country had something to do with India; and if it has its rights, if it draws millions and millions a year from India, it has also its duties. And the first time this was ever admitted was on the occasion I have referred to by the right hon. Gentleman the Prime Minister. We regard it as a great departure in the administration of the country.

Now, I urge that there is a large Military and also Civil expenditure upon Europeans. It is avowedly declared—over and over again we have been told—that a British Army and some British Civil Service in India are necessary for the maintenance of the British power, as well as in the interests of India. That in order to maintain British power there must be a certain amount of British Army nobody denies; but the question is whether the employment of this British Army is entirely for the interests of India alone, or whether it is not also necessary for the maintenance of the British power in India? In other words, are not the two countries equal partners in the benefit to be derived from the European Services; and, if so, should not England pay for this as well as India? I urge the consideration of this upon the House.

I say that part of the military expenditure is for the interests of the British Empire; that the maintenance of this Army involves the interests of Great Britain as well as India, and that both should equally share the expenditure for the maintenance of the British power in India and for the protection of British interests there. I may have to say a great deal upon this subject, but considering the time we have at our command I will be very brief. I would only say this: that on the discussion which formerly took place the right hon. Gentleman the Leader of the Opposition took an opposite view to the view held by the right hon. Gentleman the Prime Minister. Among the other reasons this was one of the reasons urged—that if India had belonged to an independent Ruler, like the Mogul, it would have been necessary for him to have entered into the war precisely as the Indian Government had done, and for precisely the same objects.

There was no doubt, therefore, that Her Majesty’s Government were following out a right line of policy in throwing the whole of the cost upon Indian finance. For these reasons he gave the Government his cordial support—that is to say, for throwing the whole expenditure on India. The right hon. Gentleman, however, forgets altogether that when the Mogul was the Emperor, and when the natives were a self-governing people, every farthing spent in the country on every soldier returned back to the people, whilst at the present time, in maintaining a foreign distant Power, you are drawing considerable amounts of money from the Indians for the Europeans, every farthing of which is completely taken away from the people under the present circumstances. That makes it entirely different.

When a foreign domination compels the people to find every farthing for the sinews of war, then the money does not go back to the people as it would under, a Home Ruler. That is not the position of Britain. Britain is 5,000 miles away from India, and sends thousands of Europeans and foreigners over to India in order to support her power. We have to find every farthing of the cost, and then we are told it is only what the Mogul would have done. It is as different as the poles, as the House will recognise.

It may be remembered that a few months ago a Petition was presented to this House from a public meeting in Bombay. In the Despatch quoted from the Government of Lord Lytton to the Secretary of State, he put the question in such a form that I shall be perfectly content to leave his words before the House. After making certain preliminary remarks, the Despatch goes on— We are constrained to represent to Her Majesty’s Government that, in our own opinion, the burden now thrown upon India on account of the British troops is excessive, and beyond what an impartial judgment would assign, considering the relative material wealth of the two countries and the mutual obligations that subsist between them.

All that we can do is to appeal to the British Government for an impartial view of the relative financial capacity of the two countries to bear the charges that arise from the maintenance of the Army of Great Britain, and for a generous consideration of the share to be assigned by the wealthiest nation in the world on a dependency so comparatively poor and so little advanced as India. I hope these few words will bear weight. I do not ask for a share of the Military and Civil expenditures of the European Services simply as a beggar on account of being poor, though that is a great hardship; but I ask it on the ground of justice, on the ground that our interests and British interests are practically identical, and that both have an interest in maintaining the British rule in India. The British people have a great advantage, and in justice to the Indians they should be willing to pay their share.

Now, I wish to say a little about the administration. I will say it in a very few words. As an illustration, may I remind the House that there are 37,000,000 people in the United Kingdom, and that an Income Tax of 1d. in the £1 produces above £2,250,000. India has a population of seven or six times the number in Great Britain, and yet on the 1d. in the £1 she can hardly pay, I think, £200,000. If this be not an indication of the condition of the people, of India I do not know what else is.

A short time ago I heard with very great interest the Statement on the Budget by the right hon. Gentleman the Chancellor of the Exchequer. He spoke in very warm terms of the marvellous way in which the Income Tax increased in this country, although merchants and traders were complaining of a very bad state of trade. The Chancellor of the Exchequer rejoiced that, notwithstanding this, the Income Tax was jumping on year after year. I was very anxious to hear his explanation of this paradox. I would like to give a little explanation upon it. I do not know whether it may be an exact statement of the facts, but still I will venture to give it.

Under ordinary circumstances, it is estimated that Britain draws something like £20,000,000 a year from India. I know that much more is said by some people, but I want to put it at the lowest. On the testimony of one gentleman who is generally antagonistic to the Indians—namely, the late Member for Oldham (Mr. Maclean)—£20,000,000 is about the amount. Therefore, we may take it that something like that sum is annually drawn from India. I would welcome this annual wealth being taken from India by you if we benefited as well as you. I take it as a matter of fact that with all this wealth flowing into Britain the Income Tax is increased.

I think if the right hon. Gentleman the Chancellor of the Exchequer can see his way to agree with me on this point he will show a greater sympathy with India in his dealings with the financial aspect of the Empire. I will give another illustration which will bring the matter home to the mass of the English people themselves. In India you have a vast country inhabited by people who have been civilised for thousands of years, and capable of enjoying all the good things of the world.

They are not like the savage Africans, whom we have yet to teach how to value goods. But here you have 300,000,000 people to trade with, and for 100 years you have ruled them administratively by the highest-paid Service in the world. What is the result? What does England get in the shape of commerce? England sends her exports to various countries, and there are countries which shut their doors to her trade.

But in India the trade is free; it is entirely under the control of the British themselves, and yet what profit do all the masses of the people receive? Very little. The total export of British produce to India is not worth 2s. 6d. per head per annum. If India were prosperous, if you allowed India to grow and make use of its own productions, then if you could export, say, £1 per head per annum, you would have a trade in India as you have not now in the whole world. It is a great loss to you and to us.

If the present principles of administration were reformed and changed, and brought into a more natural condition, the result would be that the trade of England would grow to an extent of which we have no conception. You would have a market with 300,000,000 people, whereas, at the present time, you are spending hundreds of thousands in finding markets which will produce nothing approaching this. But here is a market at your own doors, and you are not able to sell of your produce more than 2s. 6d. a head per annum on the population.

We know that in Native States native industry is prospering under the protection of British supremacy. The Native States have not foreigners going in and eating up their productions. They are gradually progressing in prosperity. I hope the time may come when important changes will be made in the administration of the country. I will not go into any further illustrations, but I would remind the House that Lord Salisbury has said what this policy is in the most significant terms. He has expressed it not in the hurry of a speech, but in a deliberate Minute made as Secretary of State for India. I hope his words will be digested by the House. He thinks that India only exists to be bled, and that now only those portions should be bled which are capable of giving blood. He says— As India must be bled, the lancet should be directed to the parts where the blood is congested, or at least sufficient, not to those which are already feeble from the want of it.

An hon. MEMBER Where does he say that?

MR. NAOROJI It is in a Minute made by Lord Salisbury in connection with the Famine Commission Return, No. 3,086–1, 1881, page 144. Those singular words cover the whole present policy of administration, and I do not think I need add anything to them. I will use a few words of our Prime Minister, and of other great and eminent statesmen, as to what sort of relationship there should be between England and India. The right hon. Gentleman the Prime Minister on one occasion, in 1858, quoted these words of Mr. Halliday approvingly— I believe our mission in India is to qualify the natives for governing themselves. But I would lay most stress on the words he recently expressed in this House in connection with the Irish Home Rule Bill.

He says— There can be no nobler spectacle than that of a nation deliberately set on the removal of injustice, deliberately determined to break not through terror, and not in haste, but under the sole influence of duty and honour, determined to break with whatever remains still existing of an evil tradition, and determined in that way at once to pay a debt of justice, and to consult by a bold, wide, and good act its own interest and its own honour. I appeal to no other sentiment of the British people, but leave it to their justice. It is necessary, in putting this matter properly before the House, to show how the present principles of administration in India are destructive.

I appeal, therefore, to the Government, and say that an inquiry is absolutely necessary to ascertain whether it is or not that the administration of India is based upon a principle not only destructive, but very much mistaken. This is my view. I appeal to this House to give us an opportunity of proving that the present system of administration is an unfortunate one, and that certain changes of reform would be a blessing. With regard to the extract from Lord Hartington’s speech, which I have read, I may say that that clearly shows that India is not properly governed. It is not sufficiently governed, for you cannot have the requisite number of men to govern it except from the Indians.

I will read a few words from a speech of Mr. Bright’s which are very expressive of our opinion regarding Indian government. He said— You may govern India, if you like, for the good of England, but the good of England must come through the channels of the good of India. This expresses what is desired by the people of India.

Mr. Bright further says— There are but two modes of gaining anything by our connection with India: the one is by plundering the people of India, and the other by trading with them. I prefer to do by trading with them. But in order that England may become rich by trading with India, India itself must become rich. He also says— We must in future have India governed, not for a handful of Englishmen, not for that Civil Service, whose praises are so constantly sounded in this House. On this point and in these words you have the whole Indian trouble, what the principle of the administration ought to be, and what alone will benefit both England and India.

I will just read a few words by Sir Stafford Northcote when he was Secretary of State; I have no hesitation in saying that he endeavoured to do the best for us. He tried his best to see what justice he could do to the Indians, and he expressed himself in words like these— If they were to do their duty towards India they could only discharge that duty by obtaining the assistance and counsel of all who were great and good in that country. It would be absurd in them to say that there was not a large fund of statesmanship and ability in the Indian character. I might quote something similar by the hon. Member for Kingston (Sir E. Temple).

Sir Stafford Northcote further says— Nothing could be more wonderful than our Empire in India, but we ought to consider on what conditions we held it, and how our predecessors held it. The greatness of the Mogul Empire depended upon the liberal policy that was pursued by men like Akbar availing themselves of Hindu talent and assistance, and identifying themselves, as far as possible, with the people of the country. He thought that they ought to take a lesson from such a circumstance.

Now, I do not think I need say more. I think I have made out a primâ facie case that the Indian problem is a very serious problem. As Sir William Hunter once said, it is a problem which might in 40 years become an Irish problem, but 50 times more difficult. I hope and trust that time will never come, and that such a contingency will never arise. I hope the time is coming when the natives themselves, educated and learned men, will have a voice and due share in the government of India. Everything is promising. If the statesmen of to-day will only overhaul the whole question and have a clear inquiry by independent and responsible men acting with English sense and honour and justice, then the time is not far distant when both England and India will bless each other.