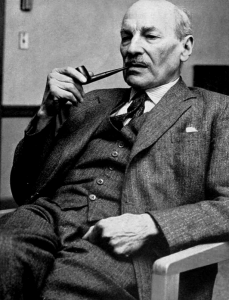

Below is the text of the maiden speech made by Denis Healey to the House of Commons on 14 May 1952.

In rising to address the Committee for the first time, I am very conscious of the need for that indulgence which the Committee is accustomed to afford so generously to maiden speakers. I have noticed that long familiarity with this peculiar ritual of the maiden birth has given the Committee the somewhat clinical attitude of a midwife towards a maiden speech. But I can assure the Committee that for the initiate concerned the act of parthenogenesis is quite as painful an experience as any that he is ever likely to endure in his life. And I count myself very fortunate in enduring this agony at a time when the midwife is in a state of twilight sleep induced by an all-night Sitting the night before.

Although I have chosen to speak on a subject which is bound to be controversial, I hope that I shall not be considered unduly partisan in anything I say, because I agree very much with the right hon. and gallant Member for Kelvin-grove (Lieut.-Colonel Elliot) that opinion on the problem of Germany is divided irrespective of party lines, and I hope I may succeed in steering a course some way between the obvious and the offensive.

The present policy of the Western world is to prevent a third world war by deterring Soviet aggression. I suggest that this policy will not be possible if the manpower and industrial resources of Germany are lost to the Western side and become available to the Soviet side, because if that happens, the balance of world power would shift to the Soviet side, and a third world war would become inevitable.

The Western world might lose Germany either through force or through the free choice of the German people themselves. The immediate danger, of course, is that we should lose Germany through force, and it is because of that danger that we of the Western world are committed to build up on the ground in Europe sufficient armed strength to defend Western Germany; that means very heavy burdens on us now, and I fully agree with those hon. Members who have expressed the view that sooner or later the Germans themselves must carry their share of that burden.

But we can also lose Germany to the Western camp through the free choice of the German people themselves, and we should be very unwise indeed to underestimate that danger when we look at the history of the last 30 years from Rapallo to the German-Soviet Pact of 1939 and watch the activities of the Soviet Union with certain nationalist and right-wing German circles at the present time.

I do not think that it is sufficiently recognised in this Committee that the destiny of Germany, now that seven years have passed since the defeat of Hitler, is certain to be decided in the last resort by the German people themselves. The victorious Powers are no longer in the position of deciding the destiny of Germany against the wishes of the German people—indeed, Western Germany alone is already, in fact although not in law, the strongest single Power on the continent of Europe—and if and when Germany is united, as in my view is certain and is desirable, Germany will once again be a world Power of the same order as Britain herself.

The problem we face in the Western world now is not, as once it was, to ensure that Germany will never be powerful again. The time for that has gone, if it ever existed. The problem we now face is how to ensure that a Germany, which is certain to become powerful, works with the Western side by its own free choice and not with the Soviet Union. As I say, it is only the German people themselves who can make that choice.

No one has realised that better than the Soviet Government because its recent notes, although ostensibly addressed to the Western Powers, were in fact directed to the people of Germany herself. We should be unwise also to underestimate the difficulty of keeping Germany on the Western side. National unity will soon become the over-riding aim of the Western German people, and Germany will go to the side which offers her the best chance of getting national unity on acceptable conditions, and she will leave any side which denies her the chance of unity under conditions which she considers acceptable.

In the long run, Russia holds all the cards because it is only Russia which can give back to Germany her unity, including not only the Soviet zone but also the provinces lost to Poland. And she would not hesitate to do so if she thought she could get an agreement with Germany.

Moreover, we have to face the additional difficulty that any agreements we make now with the Western German Government are bound to be provisional. The Germans themselves do not regard the Federal Republic as a permanent affair any more than they regard Bonn as the permanent capital of Germany. Dr. Adenauer has recently stressed this point, greatly to the dismay of the French, that any agreement accepted by Western Germany will have to be negotiated again if and when Germany becomes united, even if unity comes about under the Basic Law, because we cannot bind 70 million people to agreements which were accepted by only a majority of 47 million people.

On the other hand, the cards which Russia holds are by no means so strong at the present time, because Western Germany is extremely conscious of its weakness and its inability to defend itself. Hatred and distrust of the Soviet Union are the dominating emotions throughout Western Germany, and for that reason the German people would not at this time accept national unity if the price of national unity were the rupture of their lifeline to the West.

Like the right hon. and gallant Member for Kelvingrove and other hon. Members, I also visited Germany recently and had an opportunity of discussing this question with members of all German parties. I was surprised to find that there was almost unanimity between the Government and the opposition on the fact that a united Germany at this time could not afford to be neutral, nor could Germany accept unity without the guarantee of security.

The only thing I would suggest, and on which there is disagreement in Germany, is that we should not now commit ourselves to a united Germany having security in the form of a military alliance with the West. One criticism I would make, if it is permitted to a maiden speaker, of the reply to the Soviet note is the reference to the all-German Government being allowed to make “such defensive arrangements as it wishes.” I think that we would be unwise to insist on that, if the phrase means a military alliance. If, on the other hand, it means security against the possibility of a Soviet coup or invasion, we must insist on it, and the Germans would be united in supporting us in insisting on it.

My conclusion is that, at the present time, German unity will only be acceptable to the German people on conditions that we ourselves would be the first to insist on. Indeed, as the Foreign Secretary has already said, the Western reply to the Soviet note in insisting on these conditions has been welcomed unanimously in Western Germany.

I am extremely glad that I should be able to make my maiden speech on a day when all the doubts created by Western policy in the last few weeks have been dispersed by the reply to the second Soviet note. There has been a great danger that the Western Powers’ reluctance to enter on a new series of Palais Rose discussions with the Russians will be interpreted in Germany as a reluctance to see Germany united again. I would say that at this moment, above all, we can afford to take the offensive on the question of German unity. We shall gain much and lose nothing by doing so.

There has been a good deal of discussion in the Committee this afternoon about the dangers in the delay of the carrying out of E.D.C., and there is no doubt that many people are concerned lest the delays inevitably imposed by talks with the Russians on German unity will lose us what is considered to be the last chance of getting an early German defence contribution to E.D.C. Here I come on to ground which may be considered very controversial, but I assure the House I have no intention whatever of being polemic or partisan, and I hope that my contribution will be received as a sincere effort to think the problem out.

The first point is that if it is really true, as the Foreign Secretary seemed to suggest in his speech, that public opinion is moving so rapidly against E.D.C. that unless we can get the agreement in the bag within the next 12 months we shall lose the chance for ever—if it is a question of now or never—then the agreement will be worthless even if we get it. I apologise if I have misinterpreted the Foreign Secretary’s remarks on that matter.

The second point is that both the demand for an early German defence contribution and the agreement to treat E.D.C. as the right framework for a German defence contribution—I hope it is not impertinent to remind the Committee of this—were accepted against the will of the British Government of the day and only under very heavy pressure from our Allies.

The decision taken by N.A.T.O. in 1950 to seek an immediate German defence contribution at a time when almost none of the European peoples wanted it, including the Germans themselves—the only exceptions were the Dutch and the Danes—would never have been taken then had it not been for very strong and insistent—and legitimate—American pressure. The agreement last September to treat the European Defence Community as the right framework for a German contribution would never have been accepted by N.A.T.O. had not our French ally said that they would not accept a German defence contribution in any other framework.

I hope it is not impertinent to remind the Committee of that fact, because my view is that the present commitment of the Western world to E.D.C. and to an immediate German defence contribution arises out of the panic induced by Korea. It represents a false start in solving the German problem, and we should be prepared to welcome the pause imposed by events in order to get back on the right road.

On the question of a German contribution, I believe that General Eisenhower was quite right in his immediate and instinctive response to the suggestion when he took up his command, when he said, “I do not want any unwilling soldiers under my command.” It is the case that, for whatever reasons—and for very many varied reasons—at present the majority of the German people, and the overwhelming majority of the Germans of military age, do not want a German defence contribution. Incidentally, the Western Powers have got into appalling difficulties by treating the Contractual Agreement, as the Foreign Secretary said, as a sort of bribe in order to buy unwilling German soldiers. We should have got the agreement through without the slightest difficulty if it had not been tied to the European Defence Community.

On the other hand—I disagree with some of my hon. Friends on this point—although public opinion in Germany is at present opposed to a defence contribution, public opinion will change very rapidly and very dramatically, possibly within the next 12 months, and once the Germans want to re-arm we shall not be able to stop them even if we want to. In other words, German re-armament in the short run is impossible; in the long run it is inevitable. It is entirely a matter of timing. “Ripeness is all” in the case of the German defence contribution.

What I suggest we should do is use the time still available to us, before the Germans want to make a defence contribution, in order to consider very seriously and quietly, and not in a panic, what framework will be best suited to contain a German defence contribution. No one can fail to recognise that, although a German defence contribution would bring great gains to the West, it would also carry very great dangers. We must choose a framework which will be strong enough and large enough to attract the Germans and to hold them for good. It is no good trying to force Germany now into a mould which she will crack when she becomes stronger.

Last September the Western Powers agreed to use E.D.C. as the framework for a German defence contribution only because France would accept no other. However, I suggest that it is becoming quite clear that the French themselves, who were the only people who wanted it in the first place, have now lost faith in E.D.C. as a means of controlling German re-armament.

E.D.C. can control a German defence contribution only if the non-German components are stronger than the German components. It is already evident that Western Germany alone would be stronger in E.D.C., in fact if not in form, than France, because of France’s great commitments outside Europe in Indo-China, and, indeed, stronger than all the other members of E.D.C. put together. The result is that the French are beginning to realise that E.D.C., which they first saw as an instrument to control Germany, will turn out to be an instrument by which Germany can militarily dominate Western Europe.

In any case E.D.C. cannot offer a longterm solution to the German problem because, as Dr. Adenauer has said, when Germany is united she will have to renegotiate all the agreements which she has made, whether E.D.C. or otherwise, and it would be very dangerous if we got into a position where the importance of a German defence contribution through E.D.C., once it was set up, became such that we were compelled to oppose German unity for fear of losing that contribution under those conditions.

There is a French proverb—I shall not try to give it in French—which says, “There is nothing which lasts like the provisional.” That proverb will not be very popular in Germany, and there is a very great danger in creating at this stage vested interests in a provisional solution which cannot possibly last into the future

The French see only one way out of their dilemma, and that is to get Britain into E.D.C. to balance the power of Germany. But Britain cannot join E.D.C., first, because of its federal structure and secondly, because it has become a cardinal principle of British policy since the war not to accept additional commitments in Europe which might be treated by America as an excuse for reducing American commitments. That principle can be differently expressed as “We should try to avoid accepting new commitments in Europe which we cannot get the Americans to share.”

The French are quite right in thinking that, if Germany is to be controlled in the future, Britain and America must have a hand in the controlling, but a guarantee from Britain and America to E.D.C. of such a nature as to prevent a German secession would be both impossible to frame and impossible to fulfil. There is only one way by which the French can get what they want, and that is by having Germany re-armed within the only framework in whose integrity Britain and America have a direct and vital interest, and that framework is the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation.

I see the Foreign Secretary pursing his lips. He is right. That prospect at the moment dismays the French. But surely it is not beyond the resources of the Foreign Secretary’s diplomacy to show the French that, if they really want Britain and America involved in the longterm control of re-armed Germany, they must put Germany into the organisation in maintaining whose integrity Britain and the United States have an absolutely vital and permanent interest.

I do not suggest that we should now invite the Germans to enter the Atlantic Pact. This is entirely a matter of timing. It will be some time before the Germans themselves want to be re-armed under any circumstances. What I suggest is that we should use that time to strengthen N.A.T.O. so that it is capable of receiving this formidable new recruit. On the other hand, we must have more N.A.T.O. troops in Europe and, in particular, more French troops; and, on the other hand, we must tighten and more closely integrate the structure of N.A.T.O. I personally would not exclude tightening the military structure of N.A.T.O. in S.H.A.P.E. on the technical lines already found practical in E.D.C. That is the only way out of the problem.

To sum up, the problem of keeping a united Germany in the Western camp and out of the Soviet camp is the most crucial and urgent problem facing the whole of the West for many years ahead. In my opinion, in the panic following Korea, the Western Powers made a false start; but a pause is now imposed by events. It is our duty to make it creative. I am one of those who believe that the ever closer unity of the Atlantic peoples is one of the most fruitful developments of the postwar era. And I am convinced that it offers to us the one real chance of solving the perennial problem of Germany.