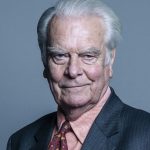

Below is the text of the statement made by David Owen, the then Foreign Secretary, in the House of Commons on 7 November 1978.

I think that the whole House would like to pay tribute to John Davies, who would have been speaking in this debate. We were all extremely sad to hear of his illness, and we all wish him a full recovery. He came into the House after a distinguished career in industry, and he deservedly built up a reputation of somebody who was fair and honest and objective in his comments. He will be missed from our debates.

I shall try at the outset of this two-day debate both to deal with the current situation in Rhodesia and to set it in the context of the report by Mr. Bingham and Mr. Gray, which investigates in detail the way in which oil had reached Rhodesia since 1965. The report is a model of careful research and balanced judgment. It brings out a whole range of facts and issues and provides helpful background for the specific debate tomorrow night on the order to renew section 2 of the Southern Rhodesia Act 1965.

The report explains in the preface that no general attempt was made to relate it to the political, diplomatic and economic events of the time. This was not part of Mr. Bingham’s and Mr. Gray’s task, which was essentially to establish the facts concerning the supply of oil to Rhodesia and to investigate evidence relating to possible breaches of British sanctions controls by British nationals or companies subject to British law. It is for this House in the first instance and Parliament itself now to set the report in its wider political context, to consider the full implications of its findings, to establish such further inquiries as it thinks necessary and to learn the appropriate lessons for the future.

To consider the facts, objectively it is necessary to recall the climate of the time and some of the political and economic factors which influenced past Governments in their framing of policies towards Rhodesia. It is not my intention to pass judgment now upon the actions of past Governments. I know that many members of those Governments will wish to speak both in this debate and when the report is discussed in another place.

Only one month after Rhodesia had become a colony in rebellion against the Crown, oil sanctions were imposed by Britain acting under a non-mandatory resolution of the Security Council. The then Labour Government had forsworn the use of armed force—

Mr. Geoffrey Robinson (Coventry, North-West)

Cowardly.

Dr. Owen

—but realised that the measures taken immediately after Mr. Smith’s illegal declaration of independence would not prove sufficient in themselves for the short, swift campaign against the regime which was then envisaged.

From the first there was always doubt whether international co-operation in an oil embargo would be forthcoming. In particular, it was obvious that Portuguese and South African co-operation would be essential if oil sanctions were to be fully applied. It was believed at the time that the closure of the principal route for the supply of oil to Rhodesia— the Umtali pipeline—could deal a major blow to the Rhodesian economy and bring about an early return to legality. The Government decided to impose oil sanctions unilaterally on 17th December 1965. No oil entered Beira in Mozambique after that date, and none reached Rhodesia’s only refinery after 31st December. The refinery has remained closed ever since then.

Early in 1966 there were reports of pirate tankers bound for Beira. These were intercepted, first with the authority of flag States concerned and then with the authority of Security Council resolution 221 of 9th April 1966. Mr. Bingham has described in some detail the action by the Government over this period.

It is now alleged that the Beira patrol, which was maintained by successive Governments from April 1966 to June 1975, when the Portuguese pulled out of Mozambique, was ineffective and a waste of taxpayers’ money. It is perfectly true that it did not achieve the initial objective which the Government had hoped for, of cutting off all oil supplies to Rhodesia, but it did ensure that oil never reached Rhodesia from the quickest and cheapest route, namely Beira and the Umtali pipeline. Hon. Gentlemen can laugh about it, but it was an extremely important policy objective, which they sustained throughout the periods that they were in Government.

At any time to have lifted the patrol and thereby acquiesced in oil flowing along the pipeline would not only have reduced the economic costs of alternative supply routes; it would have been a significant political act tantamount to recognition of the illegal regime. Successive Governments openly and publicly acknowledged that the route, initially through South Africa, subsequently through Lourenço Marques and then again through South Africa, remained open. Yet no Government from 1966 onwards were prepared to use force to close these alternative routes. It was optimistically hoped that diplomatic pressure and considerations of self- interest would bring the South African and Portuguese Governments either to re-examine their sanctions policy or to use their political influence on the regime to achieve a settlement. Events have shown that that was much too optimistic an assessment.

The House must appreciate the complexity of the factors which influenced successive Governments’ thinking during this period. Those who were responsible for policy towards Rhodesia had to weigh the implications of every action they took across a complex field of interrelated and often contradictory policy objectives for the prospects of successful talks with the Rhodesian regime, which were continuing throughout this period, for our relations with Commonwealth countries and the international community as a whole, for Britain’s own economic well-being, often coinciding with times of acute domestic economic difficulty, for the effect on Britain’s extensive commercial and investment interests built up over many years in South Africa, and for South Africa’s willingness to exercise a moderating influence on the regime.

During this period some of our major allies lacked any enthusiasm for the implementation of even existing sanctions. There is no joy in laughing at that inability to mobilise international opinion. Many of them also certainly had no sympathy or support for any measures designed to strengthen those sanctions.

The House should not forget that BP and Shell were not the only oil companies. The French and American oil companies—Total, Caltex and Mobil— appear not to have been influenced let alone controlled by their Governments. Moreover, chrome, for example, was reaching the United States from Rhodesia for many years before the 1971 Byrd Amendment actually gave congressional approval for breaking mandatory United Nations sanctions.

I mention these facts just to stress that the international climate is very different now and, most important of all, that the attitudes of the French and the United States Governments are much more sympathetic now to the views of African countries and a firm United Nations-backed policy.

The most difficult decision, and the one which the Government between 1966 and 1968 agonised over most, was how to stop oil getting through Lourenço Marques to Rhodesia, once it became obvious that it was moving on from Beira. It was felt, rightly or wrongly, that there was no practicable way of monitoring or controlling the flow of oil through Lourenço Marques without a major confrontation with South Africa, to whose law the South African subsidiaries of the oil companies were subject. Much of the oil passing through Lourenço Marques was earmarked for the Transvaal province of South Africa, for Botswana and for Swaziland.

It was established from the start and maintained as a policy by successive Governments that the burden which any economic confrontation with South Africa would entail should not be borne by Britain alone among the Western nations. There was never any attempt to conceal this fundamental conviction from Parliament or the country. As any hon. Members who were in the House at that time will attest, as a matter of political judgment taken at the highest level of Government decision-making, action was ruled out if it was thought it would lead to Britain facing economic confrontation with South Africa without the full support and involvement of some other Western industrialised countries as well.

Other Western countries were as reluctant as Britain to face an economic confrontation. It was not until November of last year that it was finally agreed in the Security Council to put a mandatory arms embargo on South Africa, though Britain had, with a few exceptions in 1970–71, particularly been operating its own arms embargo since 1964. Even today, with the international climate far tougher towards South Africa and its policies, we and our Western allies still judge it to be far preferable for everyone —ourselves and those living in Southern Africa—to avoid confrontation. But to do this South Africa must use its influence over Namibia and Rhodesia in concert with the international community rather than against the international community and must also start to dismantle the institutional framework of apartheid. An economic confrontation with sanctions over South Africa may come. But let no one be under any illusion; this is not a course which should be relished by anyone who has the interests of the people of Southern Africa at heart, for those whom we do not wish to hurt will suffer most.

After the failure of the 1966 “Tiger” talks, the Government proposed the resolution which was adopted by the Security Council on 16th December 1966, imposing mandatory sanctions on Rhodesia’s major exports and on certain key imports, including oil.

Throughout 1967, the Government conscientiously sought to find ways of intensifying oil sanctions. The Bingham report describes 1967 as a year

“dominated by a series of initiatives taken by HMG to make the oil embargo against Rhodesia effective”

but observed that at the same time the problems of enforcement became plainer. Chapter 6 of the report sets out in detail some of the schemes advanced by the Government and discussed with the oil companies. All were eventually rejected on one or more of the following grounds.

The first ground was that the refusal of Portugal and South Africa to apply sanctions left a gaping hole in the blockade of Rhodesia, which I have already mentioned.

Secondly, it was felt that certain courses of action could lead to the economic confrontation with South Africa which had been ruled out.

Thirdly, the reluctance of certain Western Governments at that time to put pressure on their oil companies, and the wider political arguments against attempting to exercise legal control over subsidiaries of United Kingdom companies operating abroad, meant that the oil companies could hide behind South African legislation. The legal problems were seriously explored at the time. They involve the whole question of the control of multinationals.

Fourthly, there was reluctance for the Government to act alone, without effective support from their partners. This in turn meant that the various schemes to ration supplies of oil or oil products through Lourenço Marques were all reluctantly—and, after reading all the relevant papers, I stress the word “reluctantly”—judged to be unworkable.

In July 1967, and again in March 1968, the Government actively considered the possibility of a naval blockade of Lourenço Marques as well as Beira. The South African Government would not have prevented oil supplies reaching Rhodesia from South African suppliers should supplies through Mozambique cease and we were not prepared to threaten a naval blockade of South Africa. Despite the Salazar dictatorship, Portugal had been allowed to be a member of NATO, and this was also a factor which was considered. The American and French Governments of the time were judged as unwilling to agree to any blockade. A blockade which tried to ration imports of oil or oil products by limiting them to the needs of normal non-Rhodesian customers, including those in the Transvaal, Swaziland and Botswana, was seriously considered but eventually judged to be impossible to administer.

A limitation of oil imports to a level below the normal demands of Mozambique, the Transvaal, Botswana and Swaziland would have entailed enforcement action against Mozambique and South Africa. There was no possibility that other international oil companies, which had their own interests both in Mozambique and in South Africa, would join in any rationing scheme. Whether one agrees or disagrees with the political judgments of the time, no one reading all the papers as I have done can make the charge of complicity, deceit or double-dealing. Here were honest men of successive Governments struggling with massive political problems, seeking the best solution bearing in mind all the restraints and all the limitations within which they felt they had to operate.

By the end of 1967, Britain was grappling with the economic crisis which followed devaluation of sterling, and the Rhodesian authorities seemed more intransigent than ever. There was good reason to believe that support in many countries for the maintenance of sanctions was wavering and that the introduction of new sanctions would cause difficulties with our partners. In these circumstances, as the report records, Ministers decided collectively to defer further consideration of proposals to intensify sanctions, including the possibility of stopping the supply of oil to Rhodesia through Mozambique. Yet, even so, as I have mentioned, a further study was made in 1968 of the possibility of rationing oil supplies to Lourenço Marques following the widespread outburst of indignation against the Rhodesian regime for its execution of a number of Africans despite the exercise of the Royal Prerogative of Mercy. The Government, however, reluctantly again reached the same conclusions as they had in 1967.

It is against this background and in this political climate that I suggest Parliament should view the discussions which those Ministers directly involved had with the oil companies in 1967–69. I think it is important to stress, as indeed the report does, that it was only towards the end of 1967 that the Government began to suspect that British oil companies and their subsidiaries were involved, directly or indirectly, in the supply of oil to Rhodesia. It was widely assumed at the time, though not then proved, that the French company CFP, as the company most heavily involved in refining and marketing within Mozambique, was principally to blame. The Portuguese authorities had alleged that British oil companies were involved, but they did not produce firm evidence, and the oil companies themselves had rejected these allegations.

The Government’s own investigations had suggested that any refined oil products delivered to Lourenço Marques for bulk storage by British companies—themselves only a small proportion of oil imports into Mozambique—were largely destined for the Transvaal. It was thought possible, however, that some of the oil companies’ customers were reselling oil to Rhodesia. It was at this point that the then Commonwealth Secretary decided to meet the directors of Shell and BP, with the outcome that is recorded in the Bingham report. The actual records of the subsequent meetings are printed in the annex to the report.

I do not want to judge or justify now, the positions which were then taken in relation to what was said to the companies, the consideration given to it in Government, or on the question whether there should have been a reference to the Director of Public Prosecutions. Parliament and the country will hear from those who were directly involved. It is, however, the public dispute about exactly what happened over this period that has, above all, made people call for a further inquiry. It is in revealing exactly what did happen at this time that I believe our parliamentary debates can now add an important dimension. Decisions throughout this period were taken in the full recognition that the denial of British oil to Rhodesia, while a necessary political instruction and legal obligation, would not and could not in itself reduce Rhodesia’s capacity to obtain oil.

Whatever conclusion is reached about the legality, the morality or the justification for this swap arrangement, we must not delude ourselves into believing that Rhodesia’s imports would, in practice, have been seriously restricted if British companies and their subsidiaries had simply pulled out of the South African market in an effort to avoid any direct or indirect involvement in the supply of oil to Rhodesia.

Mr. Alexander W. Lyon (York)

Is it at this point in the narrative that my right hon. Friend ought to indicate his view that Parliament should have been informed that we were engaging in the swap arrangement which was manifestly against the spirit, at any rate—and I suggest the letter—of the mandatory regulation that we had passed?

Dr. Owen

I am trying to give an objective account of the events of this period, which is extremely difficult to do, and I have therefore decided not to make my own judgments about the morality, the justification or, indeed, the legality of the swap arrangement, and I would include in that the question whether or not Ministers should have explained matters to the House. I believe that many hon. Members will wish to comment on that issue and that it is this area which has caused the greatest concern to right hon. and hon. Members. I am trying to put the arrangement in its context and explain what I can from the documents that are available, and then I believe the House will be able to hear from people who were themselves intimately involved in the matter and to form a judgment. I believe that it is very important not to form a judgment at this stage.

Certainly, if we had been able—

Mr. Nicholas Ridley (Cirencester and Tewkesbury)

Will the House be given another opportunity to make that judgment which the right hon. Gentleman says it is very important for the House to make about the conduct of individuals and Governments in this matter?

Dr. Owen

The Government have promised to listen to this debate. We have always said that we would come first to both Houses of Parliament and listen to the debate and then reach a conclusion. Parliament itself, will be able to reach a conclusion and if the Government’s decision is challenged Parliament has ways of bringing this issue to them. Indeed, the Government have ways of bringing this issue to Parliament.

The Government have been totally open about the whole of the handling of this process. We established an inquiry as soon as the allegations were made. When I said that we would publish the findings of the inquiry and had to make reference to the fact that in the actual legal provision there is a proviso that I had to get the agreement of those who had given evidence to the inquiry, many people suspected that we would not publish the report of the inquiry. We did publish the report at the earliest possible opportunity, and at all stages there has been the utmost openness and candour.

I would say that if we had not made this swap arrangement we would have been spared the international and domestic criticism which has flowed from this finding in the report. But other international oil companies were in contact with agents for Rhodesia. I do not do this to explain away the decision; I do it to put it in the context in which the decision was made.

A memorandum written by an employee of BP in South Africa some years later, and quoted in the report, not only set out in full the respective market shares of all the international oil companies involved in supply to Rhodesia; it revealed in paragraph 8.39, on page 270 of the report—which is worth looking up—that another major oil company, Esso, had in 1970 offered to supply 100 per cent. of the Rhodesian market at heavily discounted prices. The offer was turned down, probably because a continued diversification of sources of supply was considered more secure. But Rhodesia would have had no difficulty in finding compensating supplies through South Africa in the event of any shortfall from one supplier. It is hard to escape the conclusion that without a higher degree of co-operation from our major trading partners than was then forthcoming, any British Government were powerless to affect the oil supply position on the ground in Rhodesia.

From 1969 until 1975 there was little change in the position. The Conservative Government of 1970 to 1974 maintained virtually unchanged all the existing sanctions, including the Beira patrol. In 1971, according to the report, the swap arrangement, which the companies had set up to take Shell Mozambique, a British-registered company, out of the line of supply lapsed and a direct supply arrangement was apparently reinstituted. It is for the DPP to decide whether there was a breach of United Kingdom sanctions legislation, but the report found no evidence that the lapse of the swap arrangement was known to the then Government. I have no way of knowing whether or not new Government Ministers were told about the swap arrangement in 1970. The report states clearly that even the London offices of the oil companies did not know about the lapse of the arrangement until 1974, and that even then the companies did not inform the Government.

In 1974, a Labour Government returned to office determined to seek any practicable way of enforcing sanctions more effectively, and I have found no evidence to indicate that Ministers were told about the swap arrangement then which could have been assumed to be still in operation though it had in fact lapsed. Particular efforts were made by the new Government—with some success—to encourage a more determined application of sanctions by our international partners, the United Nations and members of the European Community. The number of prosecutions for breaches of the sanctions controls increased.

In 1977, it became a matter of increasing concern that there appeared to be grounds for believing that the oil sanctions legislation had been circumvented and perhaps broken. On 6th July, after the Bingham inquiry had been established, I tried to persuade Mr. Rowland to release all the documents in his possession. At our meeting, I had in front of me a letter which the Prime Minister had written to Mr. Rowland on 4th July stating quite categorically that the Director of Public Prosecutions had not yet completed his consideration of the report on Lonrho. No reference was made, in any of the further letters to the Prime Minister, to his having received from me the assurances which he now claims he was given. In my meeting, and in all subsequent correspondence, it was made clear, as we would be bound to do, that any decision was for the Director of Public Prosecutions. His decision was announced last Friday.

In establishing the Bingham inquiry, the Government believed that a searching examination of the entire history of oil supplies to Rhodesia since 1965 was inevitable and right. We were anxious that all the facts should be brought to light, however unpalatable some of them might be. The Government gave every help to the inquiry and unhindered access to all the departmental papers. Once the report had been received, the Government decided that it should be published virtually in its entirety, protecting only one annex, and that on the advice of the Director of Public Prosecutions. We concluded that, before deciding what further steps to take, both Houses of Parliament should have this early and full opportunity for debate.

There has been no cover-up. There will be no cover-up. It is for the Government, this House and the country to face the implications of the report. We will listen carefully to this debate as we have promised. It will be for Parliament ultimately to decide.

Mr. Willian Hamilton (Fife, Central)

Will my right hon. Friend give an undertaking to the House, in view of what he said about unhindered access to Bingham and to the relevant papers? Will he now announce that the Government agree in principle to that unhindered access through any Select Committee that this House chooses to set up?

Dr. Owen

I imagine that my hon. Friend is referring to the question whether Cabinet papers should be made available. This is one of the issues that will be discussed in the debate. However, it is not for me to decide. These are Cabinet papers for two Cabinets, of which I was not a member, in two Administrations, and I believe that there are serious issues which the whole House will wish to consider. They concern issues of precedent and issues of trust, in which Ministers participated in the decisions of Cabinet, believing that there would be a period of confidentiality, at present a 30-year period.

The Government have not taken a view about this matter, particularly in view of the suggestion from my right hon. Friend the Member for Huyton (Sir H. Wilson), who was Prime Minister for part of this period. We shall want to consider what he has to say, the arguments which he wishes to produce, and why he thinks his suggestion would be helpful. I think that the House will need to take all these considerations into account but will wish to bear in mind that on many occasions in the past, when there has been a very good case on the issue involved for releasing Cabinet papers immediately, successive Governments have always resisted it because of the danger of precedent. This is an open issue, on which we should like to hear the views of Parliament.

It is obviously urgent to satisfy ourselves—I think that everyone in the House will agree—that, whatever was the position in the past, British oil companies and their subsidiaries are now playing no part whatsoever in the supply of oil to Rhodesia. I personally saw the oil company chairmen of BP and Shell in April last year to tell them why I was establishing the inquiry and I made it clear to them that I expected them to take firm action to close any loopholes in their or their subsidiaries’ involvement in the supply of oil to Rhodesia. The report traces the efforts made since then by the British oil companies to ensure that they and their South African subsidiaries were no longer directly or indirectly involved in the supply of oil products to Rhodesia. Last autumn Shell and BP told me the terms of the assurances which they had received from their South African subsidiaries, to the effect that these companies were not directly or indirectly concerned in supplying Rhodesia.

The report brought to light, however, an arrangement between the companies’ subsidiaries in South Africa and the organisations which continue to supply Rhodesia. The report records that, when in 1976 the supplies made by the South African subsidiaries of the British oil companies to agents acting for the Rhodesian purchasing organisation were taken over by the South African State oil company, the subsidiaries were compensated by increased access to their own customers in part of the South African market, according to a formula which took into account their previous level of supplies to Rhodesia. Such arrangements were still in force when the Bingham report was completed.

I took up this matter with the oil companies as a matter of the greatest urgency. I left them in no doubt that in my view such arrangements were totally incompatible with the spirit, if not the letter, of the assurances they had passed to me. They have now told me that, although their subsidiaries were until quite recently involved in such arrangements, these have now been terminated and their South African subsidiaries are not now involved in any marketing activity related to the supply of oil by others to Rhodesia.

I have decided to refer the details of the Government’s exchanges with the companies on these matters to the Director of Public Prosecutions so that he may consider them in conjunction with the relevant passages of the Bingham report. I have also brought to his attention further material which has come to light relating to three “spot” sales of naphtha by BP Trading—a British-registered company—earlier this year to the South African State oil company, or brokers understood to be acting for that company. Where Castrol is concerned, in view of the reference in the preface of the report to that company, the DPP will be already considering whether to investigate the matter further.

One further point remains outstanding. We are in discussion with Associated Octel, a company which has Shell and BP among its major shareholders and which supplies to South Africa a lead additive which is used in local refineries to improve the quality of petrol. This company falls outside the scope of the assurances given for their groups by Shell and BP relating to the sale of oil and oil products to Rhodesia, and we are seeking in its case also to obtain satisfactory assurances of non-involvement in supply to Rhodesia.

I have now placed Shell and BP formally on notice of the Government’s strongly held view that no company in the Shell or BP group should be involved in the supply of oil to Rhodesia, whether direct, indirect or by participation in marketing arrangements related to the supply of oil by others to Rhodesia. The Government expect that the head offices of the companies will at all times act accordingly, and in particular that the necessary steps will be taken by them to ensure that all the assurances in these matters which they have given to the Government are faithfully adhered to both in the letter and the spirit. I have sought and received undertakings that any difficulty encountered by their companies or their subsidiaries in maintaining this position will be immediately notified to the Government so that appropriate action, whether of a practical, diplomatic or legal nature, can be taken. Both companies assure me that they have put the necessary procedures into effect to ensure that this responsibility can be faithfully discharged. The Government are determined to take every step in their power to ensure that, so long as sanctions are in force, neither Shell nor BP, nor their South African subsidiaries, nor any other company in the Shell-BP groups, will ever again supply Rhodesia directly or indirectly, or enter into any arrangements related to the supply of oil by others to Rhodesia. I hope now that other Governments will feel able to take similar action in respect of their own oil companies.

One fact is, however, self-evident. It is South Africa which supplies the oil that Rhodesia needs. It is argued by many countries in the United Nations— in fact, that debate has gone on over the last week—that all oil to South Africa should be cut off. This should apply, it is argued, even if South Africa were to decide to supply Rhodesia solely from its own resources—as it could, by giving Rhodesia only the 4 per cent. or so of its total oil consumption which it currently produces from coal mined in South Africa and making up the balance from its reserves.

In a few years’ time, we estimate that South Africa could produce as much as one-sixth of its total consumption from its indigenous coal supplies. A total embargo now upon oil supplies to South Africa would therefore—bearing in mind its indigenous oil production capacity, conservation, alternative energy sources and a careful use of its substantial reserves of oil already stored in the country—take full effect only over a period of some years. It is not, therefore, a sanction which would have an immediate effect in terms of oil, although it could have a psychological effect.

No one can say that such an embargo will never be introduced, but such sanctions could be justified only by a situation of the utmost gravity. Some understandably argue that we face such a situation now in Rhodesia. Others believe that we have reached this situation over Namibia. We have to consider all this, with our partners, in the context of the important negotiations that we are trying to carry forward. The pressures are undoubtedly mounting. It is in the self-interest of the South African people that their Government—as we have urged them to do over Namibia—should work with us for United Nations—supervised elections in Namibia and for a negotiated settlement in Rhodesia on the basis of the most recent Anglo-American proposals. There may be only a few months left in which to settle these issues. Instead of resting South African policy on the self-interest of the DTA Party in Namibia or on the Rhodesian Front Party in Rhodesia, it is time that South Africa took a broader view of its own interest

South Africa’s refusal to apply the sanctions laid down by the United Nations has meant that sanctions could not by themselves have compelled the illegal regime to accept majority rule. The failure of sanctions stimulated the armed struggle. In the first few years after the illegal declaration of independence, it was hoped and believed by many hon. Members in this House that sanctions could achieve majority rule peacefully. Yet those who now spend their time castigating the Rhodesian Africans who took up the armed fight for their freedom would do well to remember that their undermining of the effectiveness of sanctions has fuelled the arms struggle.

Mr. Eldon Griffiths

Can the right hon. Gentleman say what is the logic of not applying sanctions to South Africa yet continuing to apply them to Rhodesia? Why does he not come clean and say that we cannot afford sanctions on South Africa and, therefore, that sanctions against Rhodesia will not work?

Dr. Owen

I do not think that anyone could claim that I have tried to hide the economic background against which the sanctions policy has been developed under successive Governments. I have never believed that it is worth attempting to carry out a policy, either foreign or domestic, on the basis of trying to hide information. It is better for people to face the facts, and I have been very open about our involvement in South Africa. The logic is that I believe—as I have explained, and will continue to explain about sanctions, and hon. Members will have a chance to debate this later—that to lift sanctions would be seen as a political act at a time when I believe that it would be extremely foolish to take that act. Those hon. Members who have always held this view about sanctions ought seriously to consider the stance that they have taken over the past 13 years.

It would be totally wrong to argue now that, because sanctions failed by themselves to bring about majority rule, the maintenance of sanctions was a waste of time or, as some have alleged, a farce. Sanctions have been a clear demonstration of a national and international resolve not to accept UDI. [Interruption.] I know that Opposition

Members do not like this, but they are going to hear it, because it is time the consequences of some of their actions were brought home to them. Despite the fact that a group of people have constantly refused to face this situation, this House, under successive Governments, has not been prepared to accept UDI and has not been prepared to underwrite the regime’s refusal to accept majority rule. That position should be maintained.

Over the years, sanctions have had a steadily debilitating effect on the Rhodesian economy and, more recently, have been enhanced by a world recession. They have been part—only part—of the outside pressures imposed on the regime.

The wish to secure the lifting of sanctions has been an influence on, though certainty not a determinant of, the policy of the illegal regime. As the armed struggle has intensified and as world opinion has toughened, the regime has begun to shift its ground. While rejecting the inclusive settlement proposals put down by ourselves and the United States last September, it nevertheless felt obliged to work for the exclusive “internal settlement” signed in Salisbury on 3rd March. As part of that agreement we were promised elections in December. These, it appears, may not now take place and may be postponed to the spring —we are told, for technical reasons.

Yet, ever since March, private briefings to civil servants and others, not only from Mr. Smith and Mr. Van der Byl, but from other members of the regime, have demonstrated that they at least had little intention of keeping to the December date. So it comes as little surprise to those who doubted their sincerity that the election date may now be postponed.

To those in this House—and there are some—who genuinely feel that the internal settlement could still enable fair and free elections to be held in a manner which could satisfy the Africans on the basis of the fifth principle—we can never rule out this possibility—there are very strong arguments for maintaining sanctions. Otherwise, the elections may be postponed from December, possibly never to take place. Sanctions were never relaxed throughout the period of successive Governments and throughout even the period of the Pearce Commission. To lift sanctions now would be to give up the one peaceful pressure that we have, first, for a proper negotiation at an all-party conference and, secondly, to honour even the terms of the internal agreement of 3rd March.

To those in this House who genuinely believe that the internal agreement cannot provide a settlement capable of being endorsed by this House, that elections cannot be fair in the present atmosphere of violence and martial law, and that only an all-party conference followed by agreement on the basis of the Anglo-American plan can provide for a genuine transfer of power to majority rule acceptable to the people of Rhodesia as a whole, there are, similarly, very strong arguments for continuing the pressure of sanctions. Those in this House, however, who support Mr. Smith, and have done so for very many years, will continue to argue for the lifting of sanctions. They will be joined by others who appear to believe that they now know what the people of Rhodesia as a whole want. The Pearce Commission’s findings are a reminder of the dangers for us in this House of trying to interpret the minds of the Rhodesian people.

At the time, many people thought that it was a simple matter for the Pearce Commission to report that proposals negotiated by Sir Alec Douglas-Home were favoured by the people of Rhodesia. The real argument of many of those in this country who want sanctions lifted is that they do not want—some never have wanted—genuine majority rule.

Mr. Ronald Bell (Beaconsfield)

The right hon. Gentleman has made many references to people, such as myself, who have held these views. Will he help us, and perhaps the House, by clarifying our minds and his own about what he means by majority rule? Will he relate it to something that he sees in one of the African countries around Rhodesia?

Dr. Owen

There is a country which has shown a good example of majority rule and democracy which happens to be alongside Rhodesia—Botswana.

But what is acceptable is the fifth principle. It is the fifth principle which successive Members of this House have subscribed to, and that is a judgment on the question whether something is acceptable to the people of Rhodesia as a whole. It is this to which we have resolutely stuck throughout this period.

The hon. and learned Gentleman and his hon. Friends have, publicly or privately, supported the regime against their own party policy or against their own Government when their party was in power, and some even supported the regime before UDI. They justify the regime every twist and turn, and they lend credence and respectability to the endless attacks on the integrity of this country. Where is their patriotism? Each year when the sanctions debate arrives they seek different arguments to justify their basic position, wholly unable to come to terms with the need for a genuine transfer of power.

The hon. and learned Gentleman poses the question what is majority rule as if he were a living example of someone who has held out for years and years for the principle of majority rule. To give him credit, he has been quite open about his position. Nobody who has been in the House over the past 10 years can be under any illusion about where the hon. and learned Gentleman stands on the issue.

Since 3rd March and the internal settlement the Rhodesian situation has sharply deteriorated. The violence has increased. Nearly 4,000 people have lost their lives within Rhodesia, while an estimated 3,000 people in neighbouring countries have been killed in the war so far this year—and that estimate may well be wrong.

Of the 3,000 primary schools in Rhodesia, 900 are now closed, and martial law is declared over roughly half the country. In whole areas of the country the Rhodesian security forces do not venture. Many of the tribal trust lands are near to being abandoned. Censorship ensures that our own newspaper and television reporting is totally inadequate, and many distinguished British reporters have been thrown out since UDI. It is hard to ensure objective reporting. The news comes from Salisbury, but the real news story is the situation outside Salisbury.

We are in grave danger in this House, and in the country, of underestimating the deterioration since March. The Catholic Institute for International Relations has produced an analysis of the situation which gives a very different account from that which we read in British newspapers. It concludes that

“the signing of the internal agreement in March 1978—because of its inherent defects— simply intensified and prolonged the struggle”.

The internal settlement, we were told by the signatories to the March agreement, had the support of the Rhodesian people. We were told that they were in contact with the liberation fighters and that they would influence them to return to Rhodesia. We were told that the war would wind down and that elections in December were a firm commitment. It is utter nonsense to pretend now that a failure to achieve these objectives can be laid at the door of the British and American Governments. Even if we had given wholehearted and enthusiastic support to the March agreement, as some hon. Members wish, and had taken sides and tried to buttress the agreement, it would not have made it any more attractive to the Rhodesian people, and probably would have hardened opposition to it. Within weeks our credibility would have been damaged by the Byron Hove incident, we would have been identified with the regime, and our credibility would have been undermined month by month, as has the credibility of Bishop Muzorewa and Rev. Ndabaningi Sithole. Our policy would have been identified with the minority whites and we would have had no standing in the world and no influence to bring about a negotiated settlement with all the parties.

To act now, as some hon. Gentlemen appear to want, in defiance of mandatory resolutions of the Security Council which we proposed and which successive British Governments have supported, would have the most serious repercussions on our political and economic interests throughout Africa and, I dare say, the world. It would certainly destroy once and for all our ability to contribute to a negotiated settlement.

We and the United States Government have put forward our own detailed proposals for a negotiated settlement to focus discussion at a conference but not to exclude other proposals. The proposals offer three options: A, B and C. All depend on full agreement by all the parties and a viable ceasefire. A and C options involve elections after six months, followed by independence. Option B is more controversial. It involves a referendum within three months on the basis of a fixed agreed date for elections and an outline independence constitution.

If endorsed, independence would be granted provided this House was satisfied that the fifth principle had been upheld prior to elections. If rejected, elections would automatically follow within six months, and independence would follow elections. The British and United States Governments have made it clear that they prefer options A or C. Option B was included in an attempt to satisfy those who would prefer self-government as soon as possible and the presence of a neutral resident commissioner for as short a period as it takes for a referendum to be organised.

I would be interested to hear the views of this House on option B and on this issue. Option B has already been criticised by some of the parties, and we have our own doubts about its merits. The proposals give the detail of a transitional constitution for a council with executive and legislative powers which could be enacted by an Order in Council under the legislative authority given under section 2 of the Southern Rhodesia Act 1965, which will be debated tomorrow night.

We believe that the council must not give dominance to either the Executive Council or the Patriotic Front if we are to develop the basically neutral transition which is essential for a ceasefire to be agreed and fair elections held. We envisage an agreed figure as commissioner being appointed to hold executive authority for all the forces of law and order with a United Nations military force and a United Nations police monitoring unit. We have made detailed proposals for integrating the forces, put by Field Marshal Lord Carver to all the parties, not as a blueprint but as a basis for further negotiations.

The whole framework depends on agreement. It cannot be imposed, and in the last analysis, if all the parties can agree to any alternative proposals, the British and United States Governments and, I believe, this House will not stand in the way. It is for the Rhodesian people and all those who intend to live in Zimbabwe to decide their destiny. [Interruption.] It is no one particular group, and there are no vetoes.

We can point the way. We can indicate what we feel is negotiable. But we are not the sole arbiters. We stand by the all-important fifth principle. It is for the people of Rhodesia as a whole fairly and freely to decide.

The Government will, therefore, in the formal debate on the order providing for the renewal of section 2 of the Southern Rhodesia Act 1965, be asking this House to approve that order.

The most important task for Britain and the United States, having forsworn force and therefore having influence rather than power—a point which the right hon. Member for Down, South (Mr. Powell) has often made—is to continue, despite all the obvious difficulties, to work for a negotiated settlement. We cannot change the minds of men. The regime can continue to berate the British and American Governments, but this hostility convinces fewer and fewer people even in Rhodesia.

What more can they do, the regime ask? The answer is clear: face reality; stop blaming everyone but yourselves; stop ignoring the evidence of the widespread hostility to the internal settlement. The parties to the Salisbury agreement who have persistently refused since April to come to an all-party conference must now recognise by their actions that the Patriotic Front, which has been ready to come to a conference since April—

Mr. F. A. Burden (Gillingham)

Humbug.

Dr. Owen

The hon. Gentleman can call out “humbug” if he likes. However, it is a fact that the Patriotic Front has been ready to come to a conference since April. We shall now face difficulties in getting members of the Patriotic Front to a conference because they will not be bombed into submission. Launching offensive raids deep into Zambia on the very day one at long last accepts a conference is not the best way of ensuring success at the conference, let alone ensuring the attendance of the other parties.

If a negotiated settlement is wanted—I am pointing to the atmosphere which has to be developed on all sides—it is time that Mr. Smith recognised, too, that accepting an invitation to come to a conference without pre-conditions means that one cannot simultaneously, first, rule out proposals for a neutral figure to hold executive power over the forces of law and order during the transition; second, rule out, as the basis for a ceasefire, serious proposals for integrating the forces currently fighting each other, by saying that that will dismantle the existing forces; third, rule out the presence of a neutral United Nations force during the transition aimed at helping to maintain law and order at a particularly vulnerable time; and, fourth, when Britain and the United States have fought against any party demanding dominance and fought against the Patriotic Front in its demand for dominance, insist on a transitional authority on the basis of the existing Executive Council with two additional seats for the Patriotic Front. Equally, he cannot insist that legislative power should remain in the hands of the Rhodesian Front parliament. If they genuinely want to end the fighting, restore legality and lift sanctions, the Salisbury parties will have to develop a more flexible negotiating position than that.

Everyone will have to compromise to make a negotiated settlement possible The compromise will either come from submission of one side through force of arms or from persuasion, with both sides recognising the horrors of a continued conflict. Britain cannot impose a settlement. We shall not, in 1978, interpose ourselves between the forces currently fighting each other and assume an administrative responsibility we have never held and which we rejected in 1965. We shall contribute fully to a negotiated settlement and to fair and free elections, but we shall not commit British troops or a British presence until there is a settlement and a ceasefire, and only as part of an international force.

We shall continue to work with the United States, our European partners, our African and Commonwealth friends and the United Nations to bring to bear the influence of the international community. We shall convene an all-party conference the moment that we think there is a chance of success. We shall not wait for certain success. We shall seek to narrow the differences and widen the areas of agreement. Above all, we shall stand by the fifth principle endorsed by this House and successive Governments and embraced in the broad framework of the proposals that we have recently put, with the United States Government, to all the parties. This is the way to the fair and free elections that I believe everyone in this House wants.