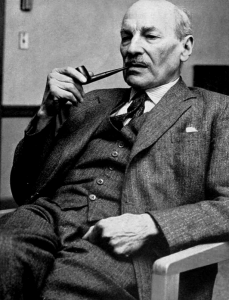

Below is the text of the maiden speech made in the House of Commons by Clement Attlee on 23 November 1922.

I want to call the attention of the House to one or two matters, which I think are matters of omission, in connection with the speech to which we have just listened. I did not notice that there was any mention of economy. We have had a great deal of talk about economy up and down this country, and we have had a great deal of talk about waste. But there is one particular waste that is never mentioned, and that is the waste of the man-power of this nation. When I throw my mind back to the War period, I remember how we were told that every man in this country was valuable, how we were told that every man was wanted either in munitions or in the trenches—men of every character, men of every capability. I heard of men who usually would not be considered sufficiently good to do any work, but who were sent to us in the trenches, because they were said to be serviceable for fighting. At that time— I think the only time in 500 years of English history—we were practically without any unemployment at all. In the district from which I come, the borough of Stepney, we always have unemployment. You may have a Free Trade system, or such a system as we have at the present time under the Safeguarding of Industries Act, which practically amounts to high Protection; but you will still have unemployment in East London. In East London we stand at the gate of England. Wealth flows through our borough up to London, but precious little stays there. We always have unemployment. The only time when unemployment was practically non-existent was the time of the War; and, despite all the rationing, despite all the food substitutes, on the whole the living conditions of our people were actually better during the War period.

I am speaking of waste from the point of view of the waste that is going on to-day of our man-power and woman-power, and of the children who are going to be the men and women of the future. In my district every day men are coming to me whom I have known years ago, and I see how they have fallen off through unemployment. You see men who were fit to be sergeant-majors in the Army —fine, upstanding men—reduced to dragging along the streets with their hands out for anything they can get. That is an enormous waste. It is not only waste, but absolute folly. We are told, and I believe it, that there is sympathy on the other side with the unemployed. I do not suppose that anyone on the benches opposite is going to get up and say that he is prepared to put the unemployed men, and their wives and families, into a lethal chamber and kill them. I think that everyone on all sides is agreed that they are to be kept alive, and the only question we have to face is whether they are going to be kept alive in fine and fit condition, or upon a dole which means that they are going steadily downhill.

The true wealth of this country is its citizens, and the finest of them, the very cells that build up our community, are the families that have a certain standard of life. Such a man, with his wife and family, with their home, represent, after all, the basis of our society, which is based upon the family. If that man falls out of work, if he comes down to a miserable wage, it means that his home is broken up, and his whole standard of life goes down and down. What you are doing with our industrial machine is allowing the spare parts to be absolutely wasted and rusted. I daresay there are hon. Members opposite who have motor cars. Perhaps they keep spare parts for them, and I expect that they look after and care for them, or their chauffeur does. The Stepney wheel is cared for as much as that which is on the car. I represent, so to speak, the Stepney wheel, the wheel which is temporarily unemployed, but which you will require in the future. My claim is that we have got to see that that reserve of labour is kept fit. When we were in the Army during the War we did not have our rations docked because we went into the supports or reserves. Our rations were the same whether we were in the front line or in the supports.

That is the first item of waste. The second great item is the loss of the services of these 1,300,000 men who are unemployed to-day. These men are capable of productive work, and there is productive work that wants doing. In my borough, which is a borough of 250,000 inhabitants, we had a very close inspection of the houses. We endeavoured to get our housing conditions bettered, and we were told that over two-thirds of our houses were not repairable in any true sense of the word. Under such powers as we had we insisted that every landlord should put his house in repair, but those houses are so utterly worn out that they cannot be repaired, but must be replaced. At the present time the country is supporting out of public funds, either national funds or local funds or funds provided by the contributions of employers and employed—I care not which you say it is; it is all coming out of the productive powers of the nation—some 100,000 men in the building trade who are not allowed to build, who are actually being paid not to build. We are almost following the bad example of the London County Council, who got out a housing scheme and then paid the contractors a sum of money in respect of every house which they did not build. We are keeping these people, though not in a state of efficiency, when we have this urgent need of housing.

The hon. Member for the Sutton Division of Plymouth (Viscountess Astor) quite properly stressed that point of housing and the intimate way in which housing is bound up with morality. We know it very well down our way. We know, too, the results of the census, which showed that in the London area alone there are 600,000 persons who are living in one-room tenements. You are not going to get an A1 nation under those conditions: you are not going to get a moral nation under those conditions; you are not going to get a sober nation under those conditions. I quite realise why the hon. Member for Dundee made the speech that he did, because, with his heart bound up with the temperance question, he knows, as we do, that we have to deal with these causes. You may produce a case here and there of abuse of the dole: you may produce an occasional man who marches with the unemployed and has a bad record; but every Member of this House who has been in a contested election and has come into personal contact with the unemployed knows that the great mass of unemployed men are those same men who saved us during the War. They are the same men who stood side by side in the trenches. They are the heroes of 1914 and 1918, though they may be pointed out as the Bolshevists of to-day.

Why was it that in the War we were able to find employment for everyone? It was simply that the Government controlled the purchasing power of the nation. They said what things should be produced; they said, “We must have munitions of war. We must have rifles; we must have machine-guns; we must have shells; we must have ammunition; we must have uniforms; we must have saddles.” They took, by means of taxation and by methods of loan, control of the purchasing power of the nation, and directed that purchasing power into making those things that were necessary for winning the War. To-day the distribution of purchasing power in this nation is enormously unequal. I recall a speech by the present Prime Minister, in which he said that one of the greatest reforms in our national life would be a better distribution of wealth among the individuals composing this nation. I entirely agree with him. While the purchasing power of this nation is concentrated in the hands of a few, there will be production of luxuries and not of necessaries. It was found necessary during the War for the Government to take hold of the purchasing power—which, after all, determines what goods shall be made—and deliberately to say that certain things were essential because we were at war, and that those things and no others should be made. They said to those who were running industry that their factories must be turned away from producing luxuries and must produce those sheer necessities. That is what we are demanding shall be done in time of peace. It is possible for the Government, by methods of taxation and by other methods, to take hold of that purchasing power, and to say that, exactly as they told manufacturers and workers that they must turn out shells and munitions of all sorts to support the fighting men, so they must turn out houses and necessities for those who are making this country a country of peace.

As the nation was organised for war and death, so it can be organised for peace and life if we have the will for it. That is why we reject all these facile assumptions that you can wait until trade is a little better. You cannot wait. The waste is going on all the time. You have only to look at the state of the children in our streets to see how that waste is going on; and if, as I hope may never happen, we should have another war in 20 years’ time, and if the Government should begin, as they did, by calling up for various years, when you come to these last three years and look at the classes of 1920, 1921 and 1922, you will not be surprised to find that a very large proportion of them are C.3. But it will be too late for yon then to complain; it will have been by your policy of tranquillity that these classes have been produced. I am not, however, concerned with producing men for war; I am concerned with producing citizens for life. I stand for no more war, and for development in peace; and I say that you are to-day in this country ruining future generations as you have ruined the present generation. It is not the fact that character is formed by unmerited suffering and privation. It simply means what I have seen for 17 years in the borough of Stepney—the boy or the man getting unemployed and sinking, sinking, sinking right down to the unemployable. We do want an economy campaign, but it must be a true economy campaign—economy in mankind, economy in flesh and blood, economy in the true wealth of the State and of the community, namely, its citizens. That can only be brought about by deliberately taking hold of the purchasing power of the nation, by directing the energies of the nation into the production of necessities for life, and not merely into the production of luxuries or necessities for profit.