Below is the text of the speech made by Neil Kinnock, the then Leader of the Opposition, in the House of Commons on 26 November 1985.

Today, as at all times when we discuss the affairs of Northern Ireland both inside and outside the House, we do so against a background of tragedy and atrocity. We think of those who have lost their lives, as the Prime Minister said, and we think of their loved ones and those whose lives have been devastated by sectarian killings and attacks. We remember those families who, when they felt the forces of violence, no matter what the status of those killed—soldiers, policemen, adults, relations or children—have always ended with a despairing question—”Why did it happen to us?” Many hon. Members have heard that question from grieving relations much too often, and, tragically those who represent Northern Ireland seats have heard it more often than the rest of us.

As we debate the accord, we remember too the courage and the fortitude of those who have lived and worked with and within the tortured community of Northern Ireland. We know that the problem of Northern Ireland, plainly, has spilled across the water and scarred Britain. We acknowledge the debt that we owe, both on the mainland and in Northern Ireland, to the civil servants, the police, Members of the House and so many ordinary men and women in Northern Ireland who have been willing to help in the search for peace and a way out of the sterile sectarian divisions.

As we think of these things, we have to remind ourselves yet again that there are matters other than security that are of importance to the people of Northern Ireland, and that there are issues worthy of report and debate other than the constant plague of conflict.

We are sometimes told that there is no solution to the historic problems of Northern Ireland, but, however difficult it may be, and however long it may take, we must never give up the search for a solution. That would be defeatism paid for in blood. If we give up the search for peace, we say to the people of Northern Ireland, “Your agony must endure for ever”. In all conscience, we cannot and must not do that.

This House has a special duty to recall that the problems of Northern Ireland are a matter not just for the Province or for the Republic but, most definitely, for Britain as well. In addition to the tragedies and their irreparable costs, there is the price of conflict which the New Ireland Forum research team has reasonably estimated to be over £9,000 million between 1969 and 1982 and a further £1,500 million or so a year with the addition of the £120 million or so a year that we spend out of public coffers in maintaining the armed forces in Northern Ireland. It is not fitting for this House remorselessly to consign such sums to Northern Ireland without at least being able to demonstrate to the people of Wales, Scotland and England that we deliberately pursue all means of achieving an end to the conflict and the massive costs that go with it.

We must also recognise that many of the legislative and other changes that have come about as a result of our inability to find a political solution in Northern Ireland disfigure the democracy of our entire country. Courts without juries, strip searches in prisons, internment without trial and many other things can be said to have arisen from the circumstances of their time, but no democracy can or should bear such changes lightly or for long, because if it does it puts at risk the very liberty that it seeks to defend.

For all those reasons, the Opposition will do whatever they can to promote the chances of peace, and the prosperity that depends on that peace, in Northern Ireland.

The status quo offers absolutely no solution to anyone at all. For that reason, we shall approve the Anglo-Irish agreement, which for reasons of accuracy and not affectation I wish had been called the British-Irish agreement.

The agreement is clearly a development from the New Ireland Forum set up in Dublin in 1983. That was a bold and visionary step taken by the major political parties in the Republic, together with the Social Democratic and Labour party.

I pay tribute to those parties and their leaders, one of whom we are fortunate enough to have in this House. None of those leaders has given up his legitimate commitment to constitutional nationalism or his commitment to the reunification of Ireland. They have recognised that, just as they cannot be forced to relinquish their aspirations of getting rid of the border, neither can the unionists be forced to relinquish their desire to keep that border between the north and the south. The constitutional nationalists have decided that, while retaining their historic ambition of unity, they will now give pre-eminence to reconciliation and a formal and binding acknowledgement of the fact that they have long recognised—that unification cannot be achieved without consent.

In the Dail last Tuesday, the Taoiseach, Dr. FitzGerald, said:

“No sane person would wish to attempt to change the status of Northern Ireland without the consent of the majority of its people. That would be a recipe for disaster and could, I believe, lead only to a civil war that would be destructive of the life of people throughout our island.”

As well as speaking for the Irish people, Dr. FitzGerald recorded the sentiments of all the British people.

That is the reward that the gunmen got for their violence. They have engendered such revulsion against insecurity, fear and brutality that they have made nationalists seek change even at the cost of indefinitely postponing their own nationalist aspirations.

The terrorists can and will treat the matter with complete cynicism. They will undoubtedly deride the action of the Irish Government and Irish political parties, and they will rely on their sworn enemies in the unionist groupings to erode and erase the agreement. No doubt that is what the Provisional IRA and the Irish National Liberation Army seek. Since they know that the most critical test of the credibility and acceptability of the agreement is its effect on security in Northern Ireland, they will continue with their terrorism and the noxious insincerity of their bullet and ballot strategy to sustain insecurity throughout the Province and in the Republic. Those terrorists, like every hon. Member, must know that the success of the agreement will be difficult to build and prove, but that its failure will be easy to contrive.

The gunmen alone cannot make the agreement fail. That outcome would need the most unholy, unsigned, unspoken alliance with those whom they most despise. Will that alliance be forged? Some hon. Members can make a major contribution to providing the answer to that. They do not belong to the Government or a future Government. They are not men of violence, and not even people who tolerate violence—to their eternal credit. They belong to the unionist parties of Northern Ireland. I recognise their fears, I know that they feel beleaguered, and excluded from designing their own destiny, that they live in constant anxiety about a sell-out, and that any failure by a British Government to explain their intentions heightens those feelings of fear. I know that they feel that deals have been done behind their back, and some will feel deep and genuine resentment at that. However modest the agreement, and however cautious and conditional the change, those feelings run deep, and in many quarters of the unionist community those feelings are absolutely genuine.

However, I cannot help thinking that there is a minority in the unionist community who quite enjoy the opportunity that is afforded by anxiety, and who will mobilise fear and bigotry in Northern Ireland. Zephaniah Williams, the Welsh Chartist, said:

“When prejudice blinds the eye of the mind the brightest truth shines in vain.”

I do not address the bigots or the wallies on either side of the sectarian divide, when I plead with the majority of non-nationalists not to be blinded by prejudice. I ask them to see that the sole beneficiaries of a breakdown would be the terrorists, that the objectives of the constitutional nationalists for the foreseeable future are limited to reconciliation and stability, and to see their acceptance of consent as the absolute precondition of any change. I ask them to see that the common cause of peace is a greater cause than the preservation of this miserable murderous status quo, and that in the agreement there is no loss of sovereignty by either Government or Parliament—certainly nothing that can begin to compare with the concessions of sovereignty that come as a natural consequence of our membership of the European Community.

I also plead with the non-nationalists to see that, if sovereignty is to be meaningful, it must involve the power to live effectively in peace under the law. Sovereignty cannot be an expression of vanity that covers the inability to rule with those conditions, like clothing on a skeleton. I ask them to see that the role of the Irish Government is consultative, and no more, that even that role can be transferred by progress with devolution, and that the basic reason for the involvement of the Irish Government, even in this capacity, is to be found in the refusal or inability of constitutional Northern Ireland unionists and constitutional Northern Ireland nationalists to share power, despite the opportunities afforded to them to do so.

I plead with them to see that the feelings of slight and suspicion, which are manifested, do not overwhelm them and leave them isolated as unionists from all those people, north and south of the border and on both sides of the water, who want to use their common longing for peace as the means of defeating violence. I ask them to recognise that the motives that led the constitutional nationalists, south and north of the border, to make the agreement are a convincing mixture of material self-interest and moral duty, not a cunning strategem for unification by stealth with the agreement of the British Prime Minister. That is the truth about the agreement.

The Irish state suffers from the contagion of violence—arms, robberies, killings, casualties, the waste of resources and the degeneration of its whole society which comes from a climate of conflict. The Republic cannot and does not want to afford that constant drain on its meagre fortunes, or the risk from it to the fabric of its society. Those are some of the pressing realities that brought Garret FitzGerald, Dick Spring and their colleagues first to the Forum and then to the agreement.

The other motivation, which is less tangible but no less forceful, of those men, whom I am happy to count among my friends, is their moral obligation towards the communities of Northern Ireland—the nationalist community, which is alienated and prey to either the temptations or the intimidation of terrorism, and the unionist community which is impaled, like its neighbours, on insecurity and estrangement.

The suspicious will understandably ask what is in the agreement for FitzGerald’s Fine Gael, Spring’s Irish Labour party and Hume’s SDLP. There are three things that are in it for them. First, there is the possibility of promoting reconciliation. Secondly, there is the practical demonstration that they are trying to fulfil their moral obligations to the whole of Ireland—the Ireland that they love with a special passion. Thirdly, there is the chance of combating the terrorists by intensified joint security measures, and by achieving extra credibility within Northern Ireland for constitutional nationalism to throw back the tide of terrorist nationalism that comes with various pretences.

All those people and parties take great risks, and bring great credit on themselves. They are earnestly trying, against all the odds piled up by history, to put the purpose of securing peace above the easier course of indulging prejudice and courting popularity. Some people in every land are paralysed by history. Others are provoked by it, and they are such people. They have decided to try to be makers of history, rather than observers of it. They took that decision in modesty and responsibility, not in vanity or ambition. They want the history of conflict and waste to be changed to a future of conciliation. They are certainly Irish nationalists, but they are front-door agents for peace, not back-door fixers of unification. Unlike many others, they have decided to be part of the answer, rather than part of the problem. For that, my colleagues and I will support them in their aims and the practical application of them.

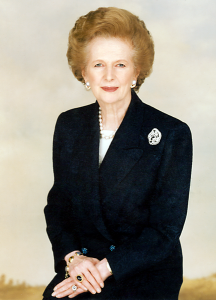

In doing so, I wish to acknowledge the contribution made by the Prime Minister to the agreement. I do not underestimate the effort that she has made, and I say without any taunt that it has involved a significant and welcome adjustment in her position during the past six years. I say further that the change is all the more credible because those six years have not only been marked by the continuing pressures of tragedy that come from Northern Ireland; they have also for her been punctuated by personal losses with the killing of Airey Neave and with the death and destruction of the Brighton bombing. I recognise her contribution freely, and I recognise it fully.

It is not, therefore, in any spirit of recrimination that I put this consideration to the right hon. Lady. The cause of this agreement would have been better served if she had taken the advice of my right hon. and learned Friend the Member for Warley, West (Mr. Archer) and my hon. Friend the Member for Hammersmith (Mr. Soley) last year when they asked her to try to spell out to the unionist communities what her intentions were in developing the relationships with the Dublin Government. That might not have assuaged all fears, it might not have silenced all the shouts, but it would have been evidence of trust and consultation which could have provided an essential credential for the agreement now.

I have to say, too, that the right hon. Lady’s response to the report of the New Ireland Forum was, as I said at the time, precipitate and peremptory. Subsequent events, including the signature of the Hillsborough agreement, have demonstrated that. My party was the only party in Britain which gave the Forum the interest which it deserved, although I acknowledge the contribution made by a section of the unionist community in providing a coherent and cogent alternative review and set of proposals. That provided an opportunity for an informed debate, but unfortunately that debate was killed before it got started. But had we proceeded along those lines the atmosphere of accord may have been more literal and the atmosphere in which the agreement has been made may have been more propitious.

We gave evidence to the Forum on 19 January 1984. We said then that the way forward lay in the joint British-Irish initiative that could not easily be vetoed by either side of the entrenched communities of the North. We are glad that the agreement recognises that. We further suggested major innovative attempts to cross-border co-operation which could lead to the closer operation of the economic and social policies of the North and South. That is also recognised in the agreement.

We suggested ways of creating links between the criminal justice system in the North and in the South and we note that the Government are at least going to consider such links at meetings of the intergovernmental conference. We endorsed the view of the report that the crisis in Northern Ireland and the relationship between Britain and Ireland required new structures that could accommodate the rights of unionists to effective political, symbolic and administrative expression of their identity, their ethos and their way of life, and the rights of nationalists to effective political, symbolic and administrative expression of their identity. The agreement establishes and defines such structural change and the accommodation of rights, and we welcome that.

That is all to the good, and I draw attention to these matters simply to show that there has been for some time a course which could have been navigated, as we recommended, in a different way and at a different speed, which might have made the circumstances of this agreement more propitious.

In addition to the matters of consultation with unionists and recognition of the validity of the report from constitutional nationalists, there is another point that I must put to the Prime Minister. It is not in any way retrospective and it has a direct bearing on the conduct of affairs and the potential of the agreement. It concerns the economic condition of Northern Ireland. As everyone knows only too well, Northern Ireland is a poverty-stricken place. It has the lowest male wages, the highest shop prices and the highest energy charges of any economic region in the United Kingdom.

The poverty is manifested in many ways, not least the high morbidity and hospital admission rates. It is also manifested among the young in the fact that a high proportion of them leave school without any form of qualification.

Most of all, Northern Ireland has a 21·4 per cent. unemployment rate, and that has increased from 9·7 per cent. in 1979. Those rates do not respect religious or political demarcations. In Craigavon and Armagh, unemployment is more than 20 per cent. In Coleraine and Enniskillen, it is more than 25 per cent. In Dungannon, Derry and Magherafelt, it is more than 28 per cent. In Newry, it is 32 per cent. In Cookstown and Strabane, 35 per cent. of the registered workers are unemployed.

Against that background, it is obvious that the agreement between Governments for the purpose of promoting common objectives of reconciliation is a fine thing and the effort at popular consent is a creditable activity. But both need a crucial further element—the prospect, at the very least, of economic development and security.

In addition to the usual arguments for fighting unemployment and sponsoring recovery, Northern Ireland has its own special and unenviable case. It is that violence cannot be excused by poverty, idleness or unemployment, but it clearly cannot be said to be unconnected with those evils. Violence, support for violence, toleration of violence may come from political fanaticism or plain gangsterism, but it can thrive on the scale of Northern Ireland only in conditions of economic insecurity and the alienation which that breeds.

[Interruption.]

I am telling the truth. I know that the hon. Member for Littleborough and Saddleworth (Mr. Dickens) is never very keen on that.

Therefore, I say to the Prime Minister that it is essential in Northern Ireland, as elsewhere, for her to adopt new policies of expansion and employment in order to stimulate recovery, to increase opportunity and to generate jobs.

[Interruption.]

Those hon. Members who are groaning now must answer the question: Do they think that an increase in employment, a reduction in unemployment and the generating of prosperity in that community would have the effect of increasing or decreasing the alienation in that community? Common sense of today, not some imagined history of which the hon. Gentleman speaks, tells us that such alienation, especially among the young, is rooted in the poverty, ugliness and strife that comes out of continual levels of economic deprivation.

We want that kind of economic development and recovery for the United Kingdom and will continue to work for it. Meanwhile, in Ireland, steps could be taken through the provisions and procedures of the Hillsborough accord, to promote the possibilities of economic development. Transport and tourism, as the Secretary of State and, indeed, his predecessors have previously recognised, have obvious possibilities for joint economic strategies, and so, too, does energy, as we have heard from many Northern Ireland Members.

What an absurdity it is that Britain can exchange electricity supplies with continental Europe but that Northern Ireland and the Republic cannot. Why do the Government refuse to put money into the Kinsale gas link when it appears that they are going to accept EEC and even American money for projects?

What proposals will the Government make for bringing the agricultural systems of North and South together so that the whole island can secure the advantages that would accompany that? Will the Government make proposals to fill the surplus college places in Northern Ireland with the students who encounter a shortage of places in the Republic?

Those are areas of action which can all give life to the words of the accord and meaning to the work of the Intergovernmental Conference. But the most useful source of reassurance and stability—I repeat it in order to emphasise it—would come from the promotion of economic recovery, deliberately and systematically by Her Majesty’s Government.

There are other areas, of course, in which the Government could work in order to mobilise support for the accord. We expect the Government to take deliberate steps to go beyond the current strategy of sending out letters and circulars in order to ensure clear understanding among the unionist and nationalist communities in Northern Ireland of the nature, purpose, potential and limitations of the agreement.

Exaggeration, either of hopes or fears, will be of no practical help to anyone. That will not impress the bullies or the bigots on either side of the sectarian divide. In any case, they are beyond communication. That still leaves a huge majority in both communities to be talked with and not talked at. There are opportunities for Parliament to communicate with the majorities in both communities, too.

We note that the Intergovernmental Conference shall be a vehicle through which initiatives regarding the wellbeing of Northern Ireland are being channelled. However, that should not obviate the role of the United Kingdom Parliament also to come forward with its own initiatives—for instance, the initiative to put into effect the recommendations of the Baker report which was debated in the House last year concerning the operation of the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1978. In addition, we need not wait upon the Intergovernmental Conference before demanding a review of the procedures for strip searching at Armagh prison, to get prompt action on a Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland and secure an early repeal of the Flags and Emblems (Display) Act 1954 that has long been sought by the Opposition.

[HON. MEMBERS: “Too long.”]

Conservative Members should be acquainted with the fact that too many people in Northern Ireland say with justification that democracy is what happens in Westminster after 10.30 pm. When we have the opportunity for a two-day debate on those matters, they can expect the debate to be exhaustive and comprehensive, covering matters that concern our fellow citizens in Northern Ireland.

Mr. Gerald Howarth (Cannock and Burntwood)

We are exhausted now.

Mr. Kinnock

The hon. Gentleman should go to bed earlier.

The agreement of Her Majesty’s Government and the Government of the Republic of Ireland to give appropriate support to the development of a British-Irish interparliamentary body is worthy of further consideration, and we shall be seeking additional details from Ministers. In that area and in many others, there are obvious obligations for everyone in the House to demonstrate interest and commitment in communicating the opportunities that can arise from the agreement.

As a matter of policy and of commitment, the Labour party wants to see Ireland united by consent, and we are committed to working actively to secure that consent. However, that is not the reason for our action in approving the Hillsborough accord. We recognise that the priority is reconciliation in the communities of Northern Ireland and between the communities of Northern Ireland. It is that objective which brings our agreement.

I do not honestly know whether at some time in the future unity will come out of that reconciliation. That can be determined only by a majority which, in future decades, will probably have different components, be in different conditions and have different leadership. However, that peace will come only out of reconciliation and the normality and confidence that reconciliation brings. Further, any unity or development towards community between north and south will come only out of that peace. As an effort for that reconciliation and for that peace, the Labour party approves the agreement.