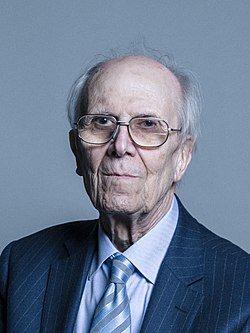

OBITUARY

Norman Beresford Tebbit, Baron Tebbit of Chingford, has died at the age of 94. A towering figure in British politics, his career was inextricably tied to the rise of Margaret Thatcher and the political and ideological battles of the 1980s.

Born on 29 March 1931 in Ponders End, Middlesex, Tebbit’s early life was far removed from the corridors of power. He was educated at the local grammar school and served in the Royal Air Force as a pilot during his national service. After leaving the RAF, he became a commercial pilot with BOAC, flying long-haul routes. He entered Parliament in 1970, winning the Epping seat for the Conservatives, before later representing Chingford from 1974 until his retirement from the Commons in 1992. His style was blunt, direct, and unapologetically combative, a tone that resonated with many during a period of deep national change and division that defined the Thatcher years.

Tebbit came to national prominence as one of Margaret Thatcher’s most loyal and effective lieutenants. Appointed Secretary of State for Employment in 1981, he wasted little time in introducing sweeping reforms aimed at curbing the power of the trade unions. The Employment Act of 1982 restricted closed-shop practices and gave individual workers greater protections against union coercion. It was one of the cornerstone measures of the Thatcher government’s agenda and marked a significant turning point in the changing balance of industrial power in Britain.

He later served as Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, where he continued his work dismantling what he viewed as outdated and obstructive elements of Britain’s post-war economic settlement. His appointment in 1985 as Chairman of the Conservative Party and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster placed him at the heart of government and firmly cemented his position as one of Thatcher’s most trusted strategists. Tebbit’s no-nonsense approach led to some of the most memorable lines in modern British political history. During the 1981 riots, he remarked that his father hadn’t rioted, he had simply “got on his bike and looked for work”. The phrase entered the political lexicon and, whether taken as a message of resilience or insensitivity, it captured the ideological mood of the time: hard-edged, unflinching and deeply divisive.

In October 1984, while attending the Conservative Party conference in Brighton, he and his wife Margaret were caught in the blast of an IRA bomb that tore through the Grand Hotel. Tebbit was rescued from the rubble with serious injuries, but his wife was left permanently paralysed. The bombing, aimed at decapitating the government, failed in its political aims but left deep personal scars. Tebbit’s response was stoic and determined, and his care for his wife became a defining feature of his later life.

He left frontline politics in 1987 to support Margaret, but his influence within the party remained strong. In 1992, he was elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Tebbit of Chingford, where he continued to make interventions characterised by the same clarity and conviction that had marked his Commons career. He was critical of the Major Government and as confusion over Thatcher’s European beliefs continued, he became an early and constant critic of the European Union, undermining the achievements of the Thatcher administration.

Tebbit was not without controversy. His comments on integration, particularly his so-called cricket test for immigrants’ allegiance to Britain, drew accusations of xenophobia and cultural insensitivity. He remained unapologetic, insisting that he was speaking uncomfortable truths others preferred to ignore. His writing, particularly in retirement, was as combative as his speeches had been. He contributed regularly to newspapers and journals, critiquing the evolution of the Conservative Party and lamenting what he saw as a loss of moral clarity and ideological backbone.

He is survived by his three children, and by the enduring legacy of a political life lived without compromise. Norman Tebbit was a man who inspired strong opinions and rarely sought the middle ground. For some, he was a warrior for common sense and national pride. For others, he was a symbol of a more unforgiving time.