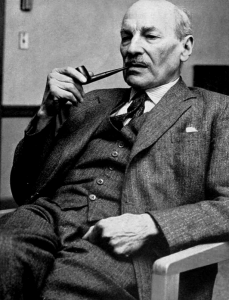

Clement Attlee – 1965 Memorial Speech to Winston Churchill

Below is the text of the speech made by Clement Attlee in the House of Lords (he was then the Earl Attlee) on 15 January 1965.

My Lords, as an old opponent and a colleague, but always a friend, of Sir Winston Churchill, I should like to say a few words in addition to what has already been so eloquently said. My mind goes back to many years ago. I recall Sir Winston as a rising hope of the Conservative Party at the end of the 19th century. I looked upon him and Lord Hugh Cecil as the two rising hopes of the Conservative Party. Then, with courage, he crossed the House—not easy for any man. You might say of Sir Winston that to whatever Party he belonged he did not really change his ideas: he was always Winston.

The first time I saw him was at the siege of Sidney Street, when he took over command of the troops there, and I happened to be a local resident. I did not meet him again until he came into the House of Commons in 1924. The extraordinary thing, when one thinks of it, is that by that time he had done more than the average Member of Parliament, and more than the average Minister, in the way of a Parliamentary career. We thought at that time that he was finished. Not a bit of it! He started again another career, and then, after some years, it seemed again that he had faded. He became a lone wolf, outside any Party; and, yet, somehow or other, the time was coming which would be for him his supreme moment, and for the country its supreme moment. It seems as if everything led up to that time in 1940, when he became Prime Minister of this country at the time of its greatest peril.

Throughout all that period he might make opponents, he might make friends; but no one could ever disregard him. Here was a man of genius, a man of action, a man who could also speak superbly and write superbly. I recall through all those years many occasions when his characteristics stood out most forcibly. I do not think everybody always recognised how tender-hearted he was. I can recall him with the tears rolling down his cheeks, talking of the horrible things perpetrated by the Nazis in Germany. I can recall, too, during the war his emotion on seeing a simple little English home wrecked by a bomb. Yes, my Lords, sympathy—and more than that: he went back, and immediately devised the War Damage Act. How characteristic! Sympathy did not stop with emotion; it turned into action.

Then I recall the long days through the war—the long days and long nights—in which his spirit never failed; and how often he lightened our labours by that vivid humour, those wonderful remarks he would make which absolutely dissolved us all in laughter, however tired we were. I recall his eternal friendship for France and for America; and I recall, too, as the most reverend Primate has said already, that when once the enemy were beaten he had full sympathy for them. He showed that after the Boer War, and he showed it again after the First World War. He had sympathy, an incredibly wide sympathy, for ordinary people all over the world.

I think of him also as supremely conscious of history. His mind went back not only to his great ancestor Marlborough but through the years of English history. He saw himself and he saw our nation at that time playing a part not unworthy of our ancestors, not unworthy of the men who defeated the Armada and not unworthy of the men who defeated Napoleon. He saw himself there as an instrument. As an instrument for what? For freedom, for human life against tyranny. None of us can ever forget how, through all those long years, he now and again spoke exactly the phrase that crystallised the feelings of the nation.

My Lords, we have lost the greatest Englishman of our time—I think the greatest citizen of the world of our time. In the course of a long, long life, he has played many parts. We may all be proud to have lived with him and, above all, to have worked with him; and we shall all send to his widow and family our sympathy in their great loss.