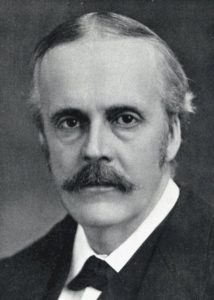

Arthur Balfour – 1901 Speech on Death of Queen Victoria

Below is the text of the speech made by Arthur Balfour, the then First Lord of the Treasury (he wasn’t Prime Minister until 1902, this was a rare period when the First Lord of the Treasury wasn’t also the Prime Minister), in the House of Commons on 25 January 1901.

The history of this House is not a brief or an uneventful one, but I think it has never met in sadder circumstances than to-day or had the melancholy duty laid more clearly upon it of expressing a universal sorrow—a sorrow extending from one end of the Empire to the other, a sorrow which fills every heart and which every citizen feels, not merely as a national, but also as a personal loss. I do not know how it may seem to others, hut, for my own part, I can hardly yet realise the magnitude of the blow which has fallen upon the country—a blow, indeed, sorrowfully expected, but not, on that account, less heavy when it falls.

I suppose that, in all the history of the British Monarchy, there never has been a case in which the feeling of national grief was so deep-seated as it is at present, so universal, so spontaneous. And that grief affects us not merely because we have lost a great personality, but because we feel that the end of a great epoch has come upon us—an epoch the beginning of which stretches beyond the memory, I suppose, of any individual whom I am now addressing, and which embraces within its compass sixty-three years, more important, more crowded with epoch-making change, than almost any other period of like length that could be selected in the history of the world. It is wonderful to reflect that, before these great changes, now familiar and almost vulgarised by constant discussion, were thought of or developed—great industrial inventions, great economic changes, great discoveries in science which are now in all men’s mouths-—Queen Victoria reigned over this Empire.

Yet, Sir, it is not this reflection, striking though it be, which now moves us most deeply. It is not simply the length of the reign, it is not simply the magnitude of the events with which that reign is filled, which have produced the deep and abiding emotion which stirs every heart throughout this kingdom. The reign of Queen Victoria is no mere chronological landmark. It is no mere convenient division of time, useful to the historian or the chronicler. No, Sir, we feel as we do feel for our great loss because we intimately associate the personality of Queen Victoria with the great succession of events which have filled her reign, with the growth, moral and material, of the Empire over which she ruled. And, in so doing, surely we do well. In my judgement, the importance of the Crown in our Constitution is not a diminishing, but an increasing factor. It increases, and must increase with the development of those free, self-governing communities, those new commonwealths beyond the sea, who are constitutionally linked to us through the person of the Sovereign, the living symbol of Imperial unity. Hut, Sir, it is not given, it cannot, in ordinary course, be given, to a constitutional Monarch to signalise his reign by any great isolated action. His influence, great as it may be, can only be produced by the slow, constant, and cumulative results of a great ideal and a great example; and in presenting effectively that great ideal and that great example to her people Queen Victoria surely was the first of all constitutional Monarchs whom the world has vet seen. Where shall we find any ideal so lofty in itself, so constantly and consistently maintained, through two generations, through more than two generations, of her subjects, through many generations of her Ministers and public men?

Sir, it would be almost impertinent for me were I to attempt to express to the House in words the effect which the character of our late Sovereign produced upon all who were in any degree, however remote, brought in contact with her. In the simple dignity, befitting a Monarch of this realm, she could never fail, because it arose from her inherent sense of the fitness of things. And because it was no artificial ornament of office, because it was natural and inevitable, this queenly dignity only served to throw into a stronger relief, into a brighter light those admirable virtues of the wife, the mother, and the woman with which she was so richly endowed. Those kindly graces, those admirable qualities, have endeared her to every class in the community, and are known to all. Perhaps less known was the life of continuous labour which her position as Queen threw upon her. Short as was the interval between the last trembling signature affixed to a public document and the final and perfect rest, it was yet long enough to clog and hamper the wheels of administration; and when I saw the accumulating mass of untouched documents which awaited the attention of the Sovereign, I marvelled at the unostentatious patience which for sixty-three years, through sorrow, through suffering, in moments of weariness, in moments of despondency, had enabled her to carry on without break or pause her share in the government of this great Empire. For her there was no holiday, to her there was no intermission of toil. Domestic sorrow, domestic sickness, made no difference in her labours, and they were continued from the hour at which she became our Sovereign to within a few days—I had almost said a few hours—of her death. It is easy to chronicle the growth of Empire, the course of discovery, the progress of trade, the triumphs of war, all the events that make history interesting or exciting; but who is there that will dare to weigh in the balance the effect which such an example, continued over sixty-three years, has produced on the highest life of her people?

It was a great life, and surely it had a, happy ending. She found her reward in the undying affection and the passionate devotion of all her subjects, where so ever their lot might be cast. This has not always been the fate of her ancestors. It has not been the fate of some of the greatest among them. It has been their less happy destiny to outlive contemporary fame, to see their people’s love grow cold, to find new generations growing up who know them not, and burdens to be lifted too heavy for their aged arms. Their sun, once so bright, has set amid darkening clouds and the muttering of threatening-tempests. Such was not the lot of Queen Victoria. She passed away with her children and her children’s children, to the third generation, around her, beloved and cherished of all. She passed away without, I well believe, a single enemy in the world—for even those who loved not England loved her; and she, passed away not only knowing that she was—I had almost said adored by her people, but that their feelings towards her had grown in depth and intensity with every year in which she was spared to rule over them. No such reign, no such ending, can the history of this country show us.

Mr. Speaker, the Message from the King which you have read from the Chair calls forth, according to the immemorial usage of this House, a double response. We condole with His Majesty upon the irreparable loss which he and the country have sustained. We congratulate him upon his accession to the ancient dignities of his House. I suppose at this moment there is no sadder heart in this kingdom than that of its Sovereign; and it may seem therefore to savour of bitter irony that we should offer him on such a melancholy occasion the congratulations of his people. Yet, Sir, it is not so. Each generation must bear its own burdens; and in the course of nature it is right that the burden of Monarchy should fall upon the heir to the Throne. He is, therefore, to be congratulated, as every man is to be congratulated who, in obedience to plain duty, takes upon himself the weight of great responsibilities, filled with the earnest hope of worthily fulfilling his task to the end, or, in his own words, “while life shall last.” It. is for us on this occasion, so momentous in the history of the Monarchy, so momentous in the history of the King, to express to him our unfailing confidence that the great interests committed to his charge are safe in his keeping, to assure him of the ungrudging-support which his loyal subjects are ever prepared to give, him, to wish him honour, to wish him long life, to wish him the greatest of all blessings, the blessing of reigning over a happy and a contented people, and to wish, above all, that his reign may, in the eyes of an envious posterity, fitly compare with that great epoch which has just drawn to a close. Mr. Speaker, I now beg to read the, Address which I shall ask you to put from the Chair and to which I shall ask the House to assent. I move—

“That a humble Address be presented to His Majesty, to assure His Majesty that this House deeply sympathises in the great sorrow which His Majesty has sustained by the death of our beloved Sovereign, the late Queen, whose unfailing devotion to the duties of Her high estate and to the welfare of Her people will ever cause Her reign to be remembered with reverence and affection: to submit to His Majesty our respectful congratulations on His Accession to the Throne, to assure His Majesty of our loyal attachment to His person, and further to assure Him of our earnest conviction that His reign will be distinguished under the blessing of Providence by an anxious desire to maintain the Laws of the Kingdom, and to promote the happiness and liberty of His subjects.”