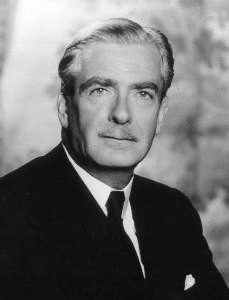

Anthony Eden – 1961 Maiden Speech in the House of Lords

Below is the text of the maiden speech made by Anthony Eden in the House of Lords on 18 October 1961.

My Lords, I hope that it will not be thought presumptuous in a newcomer if I say with what interest and pleasure I have listened to a number of the speeches in the debate in the last two days. My noble friend the Foreign Secretary, whose speech has just been referred to by the noble Lord opposite, gave us yesterday a survey of the international scene which I thought remarkable for its clarity and candour, two qualities eminently desirable in a Foreign Secretary. Also, I thought that, in the record he gave us of his stewardship, there was little that we could question. In fact, with his account I found myself almost always in close agreement.

I also enjoyed yesterday, not for the first time in my political experience, a speech by the noble Lord, Lord Morrison of Lambeth, who seemed, as I recall, to be in characteristic form, and in a vein with which I am bound to admit I have not always been in agreement. Then to-day we have had the noble Marquess, Lord Lansdowne, who has given us a lucid report on the hazardous and useful journey which he made, and on the tragic circumstances which surrounded the last hours of Mr. Hammarskjoeld’s life and his lamentable death, as we all felt it to be.

For the few moments during which I shall venture to detain your Lordships, I should like to come back to the European scene. It is about thirteen years ago that I stood where I am standing now, or a few paces to the left, to endorse, on behalf of the Opposition, the proposal made by the Labour Government of the day to take action on behalf of the Berlin Air-lift, a decision which I then thought, and still think, was both courageous and wise and, I agree with the noble Viscount the Leader of the Opposition, one for which the Labour Government were entitled to full credit.

To-day, we once again discuss Berlin, as perhaps we could not have done, had the Labour Government not acted as they did then. But, of course, it is not only the fate of this great city with which we are concerned, any more than it was only the fate of that city with which we were concerned thirteen years ago, or only the fate of Danzig with which we were concerned in 1939. The Soviet purpose is to gain possession of West Berlin, either directly or through their satellite Government in East Germany; and to do this they will employ threats, cajoleries and blandishments, hoping to prise the Western Allies out of the city, or to scare them into making concessions which will further weaken their position.

The Russians do not want war, as Hitler wanted war; but they want Berlin, or at any rate so large a measure of control in Berlin that it cannot live the kind of life which, by agreement, when the war was settled, it should live—its own life. Of course the Soviets have a great confidence in themselves, which could be dangerous to the world, and dangerous to them. It is based on a belief in their superior strength, and this may be exaggerated. The offer, already referred to, which was made in a speech yesterday at the Communist Congress in Moscow, of a respite in the settlement of the differences about Berlin and at the same time the announcement that they were to explode a 50-megaton bomb, is characteristic of a sense of overweening power. But for us, for the West, it remains an inescapable truth that if the Soviets, or their satellites were allowed to take over West Berlin, however much appearances might be saved, they would then be free to pass on to other demands, which would follow thick and fast and strong. And where should we then stop them?

We must not burden our policy with make-believe. What is at issue is not the future of Berlin, but the unity of the will and purpose of the Western Alliance and its ability quietly but firmly to say “No” to unreasonable demands. We have done so before on occasions, and it has not always been without effect. We did so about Austria; we did so when the Western Powers created N.A.T.O.—also an achievement, so far as this country is concerned, of a previous Labour Government. To hold to the essentials of our positions in Berlin does not mean that we must refuse to talk—certainly not. But for discussion to be possible there must be something to negotiate, and so far all the Soviets have done is to grab and then show a willingness to talk about the next stage in their plan. That is not negotiation. It is to ask the West to ignore violent deeds and to enter into discussion as though they had not been done. I do not think that is possible. To accept such a course would be to connive at a progressive deterioration of international relations. At each backward step the West would be so much the weaker. That way lies disaster.

This country, as my noble friend Lord Strang said last night, is not entirely a free agent in these matters. We have obligations. We played our part in the creation of N.A.T.O.; we played our part in bringing Western Germany into N.A.T.O., for which I accept, and do not regret, a personal responsibility. The N.A.T.O. partnership is the strongest political deterrent which exists to Communist world domination. But we must not think for a moment that the outcome of events in Berlin will be without its influence upon N.A.T.O. Germany’s N.A.T.O. partners have expressed opinions, as have Governments of all Parties in this country, about the future unity of Germany. They cannot go back on those decisions except by agreement.

The hope in the minds of many in West Germany is that their country will one day have reunity. It is a perfectly legitimate hope and one that successive Governments in this country have many times endorsed. It would not be loyal to extinguish it; nor would it be wise. We must guard against a tendency to speak as though British Ministers were uncommitted in these matters; as though they could in some way arbitrate. That is not their position. If we did not stand by our N.A.T.O. partners we should commit an injustice and a blunder, because we could not then complain if West Germany were to seek other means to gain German unity. Another Rapallo is not an impossibility, and it had better not be our fault.

For these reasons, my Lords, I submit that if there is to be a negotiated settlement, as I should like to see it. about the future of Berlin, it will have to contain some contribution from the Soviet side, of which hitherto, so far as I know, there has been no sign. The Soviets and their East German satellites have, in fact, already achieved a part of their purpose and have been scarcely challenged doing it. They have closed the mercy gate, which is a harsh deed. It is a deed contrary to the spirit, and I think the letter, of the Four-Power Agreement which we made at the end of the war. They are building a wall, a cruel wall, which in truth condemns them, because it is a prison wall, forbidding those behind it to reach physically to freedom. If I am right in my assumption that to build this wall is contrary to the international engagements we four Powers entered into, then this topic, I suggest, should be on the agenda when a Conference is held which includes the Soviet Power.

The most important contribution the Soviets could make to-day, if they would, to a discussion would be to show a willingness to take decisions to allow East Germany a freer opportunity to lead her own life, and to put an end to that callous rampart they have just built. In other words, what we ask for is self-determination, which the Russians so often preach but forbid ruthlessly in the territories they control.

The fact that such a settlement is so difficult for us to believe possible shows how far Moscow was challenged in taking forward positions to suit her policy. To stand firm over this issue of Berlin is not to invite war; it is the surest way to avert it. If we are firm, as I can see the Government have every intention of being firm, then we shall get negotiation. But we cannot accept a series of diktats, one after the other, nor the taint of being hostages, as I understand we have recently been described. The resumption of these atomic tests by Soviet Russia was intended to intimidate. There is no argument about that; they have told us so themselves. It was to shock the Western Powers into negotiation on Germany and on disarmament, presumably on Russian terms; and in this context Berlin and nuclear testing are closely linked. That is the reason why, though we will negotiate, and should, in certain conditions, the free world cannot yield to atomic blackmail and survive.

Soviet Russia really ought not to object if we maintain the position that negotiations can take place only on the basis of existing engagements and mutual respect. Their literature is for ever complaining of the weakness which they allege the Government’s of France and Britain showed towards Hitler’s Germany in the years immediately before the war. They roundly condemn appeasement; they indict Munich in all their propaganda. It is surely rather illogical that they should now invite us to be appeasers in our turn, and bitterly revile the Governments of the West if, having learned their lesson, they are not prepared to negotiate a Munich over Berlin.

When Her Majesty’s Government are considering whether or not there is a basis of negotiation, I should like to suggest to my noble friend a test which they might apply: it is whether the agreement for which they are working will serve only to relax tension for a while, or whether it is in the true interests of lasting peace. We must not perpetrate an injustice in order to get a little present ease; and the Government have to consider whether their decision gives peace, not just for an hour or a day or two, but in their children’s time. That is the difference between appeasement and peace. A long trail of concessions can only lead to war. I suggest to the Government four signposts as guides in these uncertain times though I admit how difficult they can be to follow: to stand by our Allies; to fulfil our obligations; to repudiate threats; and to probe for negotiation, while being beware of appeasement as I have tried to define it.

My Lords, even as it is to-day the pressure upon Communist Powers is world-wide and continuous. Berlin is, at the moment, the focal point, but there are others. In Iran every method of intimidation and subversion, as it seems, is being unscrupulously employed. There the purpose is strategic and economic; the approach to the Persian Gulf, and the control of oil, to disrupt the economies of the other nations. In South-East Asia, particularly in South Vietnam, the area that strategically matters the most, fresh efforts are now apparently being made by extensive guerrilla activities to undermine the Government of the day; while in Tibet the conquerors are established, merciless and unchallenged.

There is no reason to suppose that these pressures will subside. On the contrary, we must expect them to gather force as the Kremlin glories in the new power to intimidate, which its breach of the agreement to suspend nuclear testing is gaining for it. It may seem surprising that this action, which must to some extent imperil the future of the human race, has been so little condemned by what is usually called neutral opinion. I think the explanation is that its brutality—because it is brutal—was deliberate at that particular time in order to create fear, and in that it largely succeeded. The threat of nuclear war is for Moscow an instrument of policy.

These events seem to me to show that the Free World is in a position of the utmost danger. I said a year ago that our peril was greater than at any time since 1939. Some thought that alarmist, though I do not think anybody would think so now. Yet we are still not realising the nature of the effort which is called for from us if we are to survive against a challenge of so much ruthlessness and power. Here I am not criticising any particular Government of any country, but posing the problem as it besets the Free World. Our methods do not yet match our needs. Admittedly, machinery is no substitute for will; but unless you have the machinery even the most purposeful will cannot achieve results.

Many of your Lordships had experience during the war of the work of the Joint Chiefs-of-Staff. Without that organisation there would have been, as many noble Lords know, confusion and disarray; Allies playing their own hands in different parts of the world, often without understanding of the interests of others, sometimes regardless of them. That is exactly what has been happening often—only too often—between the politically free nations in the post-war world. We need a closer and more effective unity if we are sometimes to mould events and not only to pursue them.

We have had two examples in the last few months of the consequence of not being prepared and agreed in advance for eventualities which were not very difficult to foresee. One was the building of the wall in Berlin, which I have just mentioned. The second has been recent events in the Congo, where opinion among the Western Powers seems to have been at odds and their actions uncoordinated, even within the United Nations. I do not want to argue about what the policy of the United Nations in the Congo should be, only to say this. While it seems to me a course of wisdom to encourage confederation in the Congo. I do not believe that it is defensible to try to impose federation by force.

But however that may be, would not our policy in the Congo have been more influential if, even in the last few months, we and the United States and our other N.A.T.O. allies could have acted in unity? And should we not have had a better chance to do so if an international political General Staff had been at work to prepare joint plans in advance, as was done in war time, against a contingency which could be foreseen? I admit that to create such a political General Staff involves an act of will, overriding old jealousies and old prejudices which still exist between allies in the Free World, in what are nominally peace conditions. I therefore find it encouraging that this intention has received most support so far in the United States of America.

In conclusion, my Lords, there is just one aspect of our affairs which, since I am now out of the stream of active politics, I think I can mention without being either patronising or partisan. There is another way in which this country can influence the international scene: by the image of its purpose which it creates in the minds of other people. I do not think we can, any of us, be altogether happy about that portrait just now. That is partly because of the theme of recurrent economic crises which have been endemic since the war and which, when they are temporarily surmounted, are so easily forgotten. Immediately after the war they seemed more readily acceptable. After the prodigous national effort that our country had made, and the unstinted expenditure of our resources, they seemed excusable. But now nothing would so much increase the authority of my noble friend the Foreign Secretary as the conviction in the world that we have put these recurrent spells of economic weakness behind us for good.

I have no doubt that we can realise this, but only by a national effort in which every member of the community plays his part with a will to see the business through. This is something more important than the politics of any Party; it is our national survival as a great Power. If we can approach our economic problems in a spirit such as we have so often evoked in the past in the face of our country’s danger, selflessly, but with determination, we can solve them. We have to succeed, if our deliberations are to count for anything and if our country’s influence is to hold sway for justice and for peace.