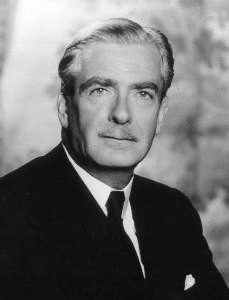

Anthony Eden – 1937 Statement on Foreign Affairs

Below is the text of the speech made by Anthony Eden, the then Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, in the House of Commons on 21 October 1937.

It is symptomatic of the state of the world to-day that our last Debate before our Summer holidays and the first opportunity for a debate on the resumption of our work should both be concerned with the foreign situation. During the period of our holiday, which I must confess seemed to me a singularly short one, the world has been far from observing the rules of August and September quietude in respect to which this House has set them so excellent an example.

Indeed, internationally the holidays have been almost stormier than term time. I will not attempt to give the House this afternoon a full account of all the events in the international sphere which have so fully occupied the chancellories of Europe and the world during the past few months. It would unjustifiably tax the patience of hon. Members. At the same time, the House will no doubt wish to have on this first available occasion some account of the main events of the Recess and some appreciation of the present outlook. In two parts of the world far removed from each other—the south-western corner of Europe and the Far East—undeclared wars are at present raging. The House will not be surprised if I confine most of what I have to say this afternoon to these two parts of the world.

I would like, for I think it is good to keep some kind of chronological sequence, to begin with events in the Mediterranean, which began to take place not very long after the House had adjourned for its summer holidays. We became confronted with what was something of a new phenomenon in the international situation. The commerce of the Mediterranean found itself confronted with a new menace. Merchant ships, neutral merchant ships, non-Spanish merchant ships were stopped and sunk, often without warning and with consequent heavy loss of life in the Mediterranean. Our own shipping, British shipping, began in consequence to suffer from what were in effect acts of piracy. That was a situation which could not be allowed to continue.

I have seen it said that the action of His Majesty’s Government in conjunction with the French Government and the other Mediterranean Powers—now all the other Mediterranean Powers—has militated against the chances of victory of one side or the other in Spain. Whether that be so or not, it is a charge to which we are quite indifferent, for the action which we took had, of course, nothing whatever to do with whatever our sentiments might have been in respect of the Spanish conflict itself. Against such acts the only possible safeguard was the use of such overwhelming strength for the protection of trade routes in the Mediterranean as would effectively deter the pirates.

There were, moreover, two conditions for such action—that it should be speedy, that it should be based on international authority. Hence the Nyon Conference. We and the French Government—the latter were the conveners of the Conference—were sincerely sorry that the Italian Government could not see its way to participate in the Conference for reasons which we need not go into now. That difficulty has since been resolved. Fortunately, however, a remarkable measure of unity manifested itself within the Conference, and within 48 hours all the necessary plans and details, both political and technical, had been agreed to by the members; and within actually less than a fortnight the decisions of the Conference, including the patrolling of the trade routes in the Mediterranean by an Anglo-French force totalling some 80 destroyers, were actually in operation. It is always dangerous to offer any prophecy in present world conditions, but it is at least true that from the Assembly of the Nyon Conference until to-day the acts of piracy against shipping in the Mediterranean have ceased.

There is one additional comment I would like to make. The rapid progress realised by that Conference was only made possible by the marked degree of co-operation between the British and French delegations, both naval and political, and, no less important, by the ready spirit of comprehension shown by the other Mediterranean Powers present. His Majesty’s Government will not cease to be sincerely grateful for the part played by each one of the signatories of the Nyon Agreement.

Now I must turn to the sphere of the international situation, which presented, and in a measure continues to present, a less satisfactory picture. The working of the Non-Intervention Agreement during this period continued to be so unsatisfactory that the French Foreign Minister, M. Delbos, not unnaturally preoccupied, as were His Majesty’s Government, by the situation, seized the occasion of a conversation with an Italian representative at Geneva to propose spontaneously Three Power conversations between the French and Italian Governments and ourselves in an attempt to improve the Spanish position in all its aspects. In the circumstances the House will appreciate that in view of the origin of the invitation there was no time for prior consultation with us, but we were prepared and are still prepared to fall in with any proposal that gives prospect of a speedy betterment of the situation. I have no doubt that M. Delbos then hoped that the improved international atmosphere created by Italy’s joining in the Nyon Agreement created an opportunity for his initiative.

The House knows the later history and I am not going to recapitulate it here. The Italian Government declined the Three Power conversations, but suggested a reference back to the Non-Intervention Committee. Despite previous disappointments the French Government and ourselves decided to make one more effort, even though it might have to be the last, to refloat the Non-Intervention Committee, which had been virtually waterlogged for two months. At the same time we thought it only fair to make it plain that if the meeting could not achieve results within a limited period we should have to be free to resume our liberty of action. I want to make our position plain to the House. That statement was made, not because we had ceased to believe that the policy of nonintervention was still the only safe course for Europe in the Spanish conflict, but because no Government can continue to associate itself for an indefinite period with an international agreement which is being constantly violated.

So we come to Tuesday’s meeting. I confess that this was my first personal experience of a meeting of the Non-Intervention Committee. I would add also that at its close I myself saw no alternative but that the meeting the next day should decide to report failure to the General Committee, with all the consequences that such a decision must inevitably entail. In this connection I understand that there have been certain reports that on the morning of yesterday His Majesty’s Government took some new decision to modify their attitude, to grant belligerent rights, or seek to grant them, at once, and attempt to withdraw volunteers afterwards. I believe it has even been said that we approached the French Government in that sense. Lest there should be any misunderstanding, not only at home but elsewhere, I think I should make it plain that there is no truth whatever in that story. But at the eleventh hour there came a new and very welcome contribution by the Italian Government. However chastened some of us may be by the international experience of the last few years, no one will, I hope, belittle the significance of this offer.

There are two points to be borne in mind which I wish to emphasise to the House in connection with it. The first is this: the chief difficulty in connection with this problem of the withdrawal of volunteers had been the relation in time between the withdrawal of the foreigners and the granting of belligerent rights. On this issue both the Italian and the German Governments have substantially modified their attitude. Secondly, a stubborn difficulty had been the question of the proportionate withdrawals from both sides. Without proved figures it was virtually impossible to reach agreement on numbers, consequently on the basis for proportionate withdrawal. Here, too, the Italian Government have proposed a solution which should be acceptable—that we should undertake in advance to agree to proportions based on the figures of the Commission to be sent to Spain, whatever its figures may ultimately prove to be. His Majesty’s Government are themselves in complete accord with this view, and sincerely appreciate the contribution to international agreement which these two concessions and the acceptance of the British plan as a whole undoubtedly imply.

I should be the last to indulge in exaggerated optimism. There are problems enough and to spare still outstanding. In any event, however, there was truth in the remark one of my colleagues on the Committee made to me as we left last night: “Yesterday there seemed to be no hope; to-day there are real chances of making progress.” Can we profit by them? The next few weeks will show, and I say “weeks” deliberately. His Majesty’s Government will spare no endeavour to see that progress, now once begun, proceeds rapidly and unchecked. With this in view the Committee will meet again tomorrow, when we hope to receive the replies of all Governments to the Italian Government’s new offer.

But while I am speaking about Spain there are some general observations about that country and the Mediterranean situation which I would like to make to the House. The Government have always maintained, not, I know, with full approval from all quarters of the House always, that the right policy for this country in this dispute is non-intervention. This was the doctrine so often and eloquently preached to us, if I remember aright, by hon. Members opposite in the early days of the Russian Revolution. The fact that others may be intervening now does not detract from the truth of the doctrine. I am convinced that the people of this country are united and emphatic in not wishing the Government of this country to take sides in what should be a matter for the Spanish people. I am also convinced that our people wish the Government to do everything in their power, by example and by conference, not to let the principle of non-intervention he finally and irrevocably thrown over, if that can be contrived.

In this Spanish conflict our determination is to concentrate on what is possible; by a combination of patience and persistence, even at the risk of criticism and misrepresentation, to localise this war; and to watch over British interests. Those seem to us our two principal tasks, and in this connection I repeat to-day what I said in North Wales a few days ago, that non-intervention in Spain must be sharply distinguished from indifference in respect to the territorial integrity of Spain or in respect of our Imperial communications through the Mediterranean. There will be no indifference on the part of the Government where it is clear that vital British interests are threatened. In matters of such delicacy and importance the House will agree that the utmost precision and clarity are called for. Let me, therefore, once again make it plain that our rearmament bears with it neither overt nor latent strains of revenge either in the Mediterranean or anywhere else. Such sentiments are wholly alien to the British character, and even were the Government of the day to harbour them, which it does not, the British people would never be willing to give effect to them. Our position in the Mediterranean is essentially this, that we mean to maintain a right of way on this main arterial road. We are justified in expecting that such a right should be unchallenged. We have never asked, and we do not ask to-day, that that right should be exclusive.

The House has been encouraged to hope by the events of yesterday that a final step forward may be made in eliminating the Spanish question from the sphere of international conflict. His Majesty’s Government most ardently hope that this will prove to be the fact, for let us be frank about the consequences. The Government are conscious, as everyone else who has watched the international situation in the past year must have been conscious, that foreign intervention in Spain has been responsible for preventing all progress towards international peace. If they had wanted to see how plain this fact is, hon. Members opposite should have been at the League Assembly this year, where despite efforts which were made, notably by my right hon. Friend the Secretary of State for Scotland, and by M. Leon Blum for France, to obtain an agreed resolution, such agreement was found to be quite impossible. So it is with every aspect of international life. This is the cloud that obscures the prospects of improving the relations between the Mediterranean Powers. It would be futile to deny that until it is finally dissolved real progress will not be possible between them. If and when, however, the Spanish question, with all its attendant problems, both strategic and political, ceases to be the nerve centre of international politics, then it will be possible for the nations of the Mediterranean to seek in friendly conversations among themselves to restore those relations of traditional amity which have governed their intercourse in the past. In such conditions there is every reason why such conversations should succeed. That is the objective which we should all like to see realised. It is one in which our whole-hearted co-operation, whatever party be in power in this country, can always be counted upon, on the condition that this problem of intervention in Spain is resolved.

I should like to make some comments, if the House will allow me, upon the other sphere of warfare, the tragic situation which has developed in the Far East. There events have been happening which, whatever their military outcome, must inevitably result in the impoverishment of both nations now engaged in the conflict, and in the loss for a while at least to the other nations of the world of the hopes that a rising standard of living in the Far East and an expanding market in that part of the world would result in increased opportunities for commerce and for prosperity for all. This country more deeply regrets these events not only because we have great commercial interests in the Far East but also because, just previous to the outbreak of this conflict, we were, as I think the House knows, actually engaged in conversations with the Japanese Government which might have led to a programme of international co-operation, including of course the co-operation of China, for the improvement of relations and the development of trade in the Far East. These conversations, of course, were interrupted at once on the outbreak of the conflict, and their resumption is clearly impossible in present conditions. At the same time I would like to give the House a condensed account of the efforts which we have made to seek a settlement of this conflict, and I shall have something to say upon its origins and responsibilities in a moment.

As soon as we received news of the outbreak of fighting in North China we made repeated attempts to persuade the two Governments to enter into negotiations with a view to settling their differences before they assumed large proportions, and we made it clear that our good offices were available at any time to them for that purpose. Equally, when hostilities seemed to threaten in Shanghai, and after they had broken out, we went further than that, for we made an offer that if the Japanese forces in Shanghai were withdrawn and both Governments would withdraw their forces, we would undertake the protection of Japanese nationals in Shanghai jointly with other Powers. Other Powers accepted that offer and so did the Chinese in principle provided it were accepted by the Japanese Government. I think perhaps everybody in the Far East regrets that that offer was not universally accepted. In all these efforts we have kept in the closest touch with the Governments of other countries principally concerned, and especially, of course, with the Government of the United States. The views of these Governments and the action which they have taken, either with the Japanese or Chinese Governments, or both, have been substantially of a similar character.

Here I would turn for a moment to League action and our part in it in connection with this dispute. On 12th September the Chinese Government came to the League of Nations and referred their dispute with Japan to the League under Articles X, XI, and XVII of the Covenant, and the Council, with the full consent and approval of the Chinese Government, referred the matter to a special advisory committee which has been responsible for following the situation in the Far East. That advisory committee met at Geneva and, very wisely, I think, came to the conclusion that a body composed of the Powers principally interested in the Far East would be most likely to find a way of composing the dispute. They, therefore, proposed that the parties to the Nine-Power Treaty signed in Washington soon after the War should Initiate consultations in accordance with Article VII of that Treaty. Such consultation was immediately initiated by cable and through the diplomatic channel by His Majesty’s Government and various other Governments, with the result that the Belgian Government, having first been assured that such a course would he generally approved, have issued invitations to all parties signatories to the Treaty to meet in conference at Brussels, and we meet there on 30th October. We hope to be able to announce in the course of a day or two the delegates who are to represent the Government of this country.

At Geneva certain pronouncements were made both about the origin of this conflict, in what I thought was an admirably drafted document by the advisory committee, and also as to the air bombing which has taken place. I will add nothing more on either of those subjects to-day, except to say that, as our own representative at Geneva made abundantly clear, we fully endorse every word of those reports and everything that they say. We welcome the summoning of this conference, because in our view a meeting of the Powers principally concerned, in the capital of one of the signatories of this Nine-Power Treaty, is the best hope of finding a means of putting an end to this unhappy conflict. I would remind the House of the initiative that the League took in the matter and of the words in which that initiative was defined.

The words are: The sub-committee would suggest that these members”— that is, the members who signed the Nine-Power Treaty should meet forthwith to decide upon the best and quickest means of giving effect to this invitation. The sub-committee would further express the hope that the States concerned will be able to associate with their work other States which have special interests in the Far East to seek a method of putting an end to the conflict by agreement. It will be seen from this that our mandate is a definite one. I would only to-day add this: naturally we are in consultation with other Governments interested and shall continue to be so up to the moment of the Conference, and I received a message to-day to say that the French Foreign Secretary will himself attend the Conference and I also learn that the Italian Government are to send a delegation while the United States Government are being represented by their Ambassador at large. But I would submit this to the House: to talk now about what is to be included in or excluded from the Brussels Conference in advance of the meeting would be most unwise. We have our definite agenda given us by the League, and I suggest to the House that the proper procedure for us to follow is, in consultation with other signatories to the Treaty who will be present, to do the utmost that lies in our power to discharge that Mandate. The paramount desire of everyone must be to see an end put to the slaughter, the suffering and the misery of which we are witnesses in China to-day. If the meeting of the Brussels Conference can achieve this—and I repeat that, in our view, it offers the best chance there is of achieving it—the Conference will render the greatest possible service. If it fails, then we enter into a new situation which we shall have to face.

Mr. Herbert Morrison Refer it to the Non-Intervention Committee, I suppose!

Mr. Eden The right hon. Gentleman will, no doubt, explain what policy he wishes to advocate. I can only say that His Majesty’s Government will enter that Conference with the determination to do everything in our power to assure the success of its labours.

So, if the House will allow me I will make one or two observations upon the international situation in general before I conclude. I would like to quote first of all from an important statement which has recently been issued on the international situation and which I read with the greatest interest. The statement said: During the past two years there is good reason to believe that Europe has more than once been on the very brink of the precipice. The position was very critical when Germany reoccupied the Rhineland. It then said: It was publicly declared by Leon Mum to have been very critical in the first weeks of the Spanish war and, as this war has continued, the danger of its spreading into a European conflagration has never been absent. Those who read that statement—[An HON. MEMBER: “Read on.”]—That statement will be recognised by hon. Members opposite. I expect they would rather say that it is all our fault. If it goes on to say that it is all our fault, they may quite believe it, but surely they are the only people who will believe it. My purpose is not to quarrel with that statement but to say that I am in full agreement with it. Unfortunately it is true, but if it is true surely it throws all the greater responsibility upon us to see that we do nothing at this time that might result in pushing us over the brink of the very precipice in respect of which hon. Gentlemen are so eloquent.

I cannot but have constantly in mind in these anxious days the phrase which was used by my right hon. Friend the Minister for the Coordination of Defence about the years that the locusts have eaten. It is impossible in the conduct of international affairs at this time, in a rearming world where, as President Roosevelt has graphically described, international law is no longer respected—it is impossible for foreign policy to be other than very closely related to the condition of our armaments. The experience of these years should be a grim warning to us and, more important, a grim warning to every future Government who hold office in this country. Now, at length, our growing strength in the field of armaments is beginning to appear, and its significance can scarcely be exaggerated. That is why I cordially welcome in this House the verdict of the recent Socialist party—Labour party—conference.

Mr. McGovern A completely National Government.

Mr. Eden It is easy for hon. Members to throw taunts about that conversion, but I, for one, will never do so because I am only too glad for that conversion, because of the steady influence I am convinced that verdict will have upon the present international situation. If it be the precursor of closer unity in other spheres, so much the better; even for what it stands for in itself it is an element for which the Government cannot be too grateful.

Mr. Gallacher It will not stand long.

Mr. Eden Whatever our party differences here, there are no Members in any part of the House who do not care deeply for the preservation of peace, and the verdict thus given, and the votes cast even before the unity arrived, are a real contribution in present conditions towards that result.